Working Paper Series no. 872: Responsibility for Emissions: the Case of the Swiss National Bank’s Foreign Exchange Reserves and the Norwegian Oil Fund

Should public investors take responsibility for the greenhouse gas emissions of the firms that they invest in? This paper answers this question through a comparative study of two very different investors: the Swiss National Bank (SNB)’s foreign exchange portfolio and the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund, the Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM), the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund. Although both funds target positive returns, the SNB presents itself as a market neutral investor, whereas the NBIM is one of the world’s leading public ethical investment vehicles. Despite having a carbon footprint 10 times higher than the SNB, the NBIM potentially has a more positive impact to stop climate change. The NBIM uses divestment, shareholder engagement and moral leadership to try to mitigate the impact of its portfolio. The SNB on the other hand has a mainly passive approach, with only some minor exclusions. Comparing the impact of their strategies, the paper provides the first detailed study of the powers available to public investors in pursuing environmental objectives.

Public investors such as sovereign wealth funds, pension funds and central banks have an increasingly prominent role in financial markets. The companies they invest in generate large amounts of CO2 emissions and have an important role to play in the transition to a “low carbon” economy.

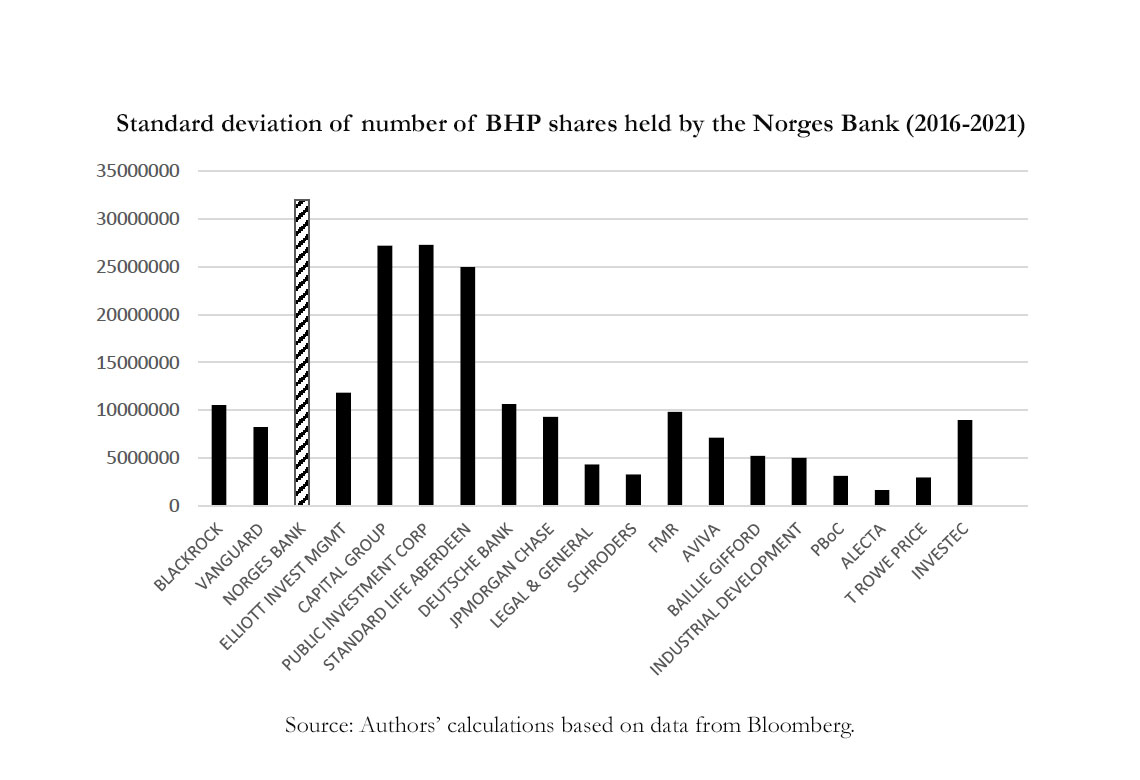

We compare two opposed perspectives on how public investment deals with emissions. The first perspective assigns to investors an “active” role, which holds that in addition to pursuing the highest returns, a public investor should also serve the common good. The iconic investor in this regard is the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund, Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM). The figure below shows the variation in its investment in BHP, the largest mining company in the world. The NBIM does not shy away from frequent investment and divestment. It is the largest public investor whose portfolio reflects an attitude of responsibility for emissions. Although the NBIM’s overriding objective remains that of generating returns, the fund also promotes decarbonization through their investment strategy.

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) on the other hand takes a “market neutral” approach, which holds that public investors should follow the market and not attempt to achieve environmental impact through their portfolio. This approach is underpinned by the view that as a public actor it is bound by a requirement of neutrality and impartiality in the treatment of market participants. It also reflects a democratic concern that climate policy should be pursued by more traditional tools of economic policy such as taxation and regulation outside the central bank’s remit.

We compare the NBIM and SNB in terms of their strategy and its impact. We focus on three aspects: portfolio policy, shareholder engagement and moral leadership. The portfolio policy sets the criteria for firms included in the fund’s portfolio. Shareholder engagement concerns the use of voting rights and other means available to asset owners to influence the corporate strategy of their issuer. Moral leadership concerns the various ways in which the fund’s investor policy, shareholder engagement and broader communicative efforts shape the investment and shareholder policies of other investors.

The NBIM is an active investor and uses shareholder engagement to encourage companies to change, notably on the issue of transition. In 2020, the NBIM had 2877 meeting with the companies it is invested in and it went to vote at 11871 shareholder meetings. One of the companies it frequently engages with is BHP, mentioned above. Part of the success of the engagement strategy of the NBIM comes from its willingness to divest from a company if it does not follow its recommendation. While this has a limite direct effect on prices as other investors will buy the shares, it works as it makes its engagement policy credible. As can be seen on the figure above, the NBIM offers the largest standard deviation in its investment among the top-20 investors in BHP. This willingness to invest, divest and reinvest makes its engagement strategy more credible than that of other large investors, which show a much lower standard deviation and tend to hold shares, regardless of the behaviour of companies.

A close analysis of the impact of the three levers provides four key results. First, we show that the widely used metric of the “carbon footprint” provides an inadequate proxy for impact. In fact, the Norwegian institution turns out to do worse than the SNB on this metric, even when adjusting for the size of their respective portfolio. That is, the NBIM has a larger carbon footprint than the SNB per dollar invested. Second, these paradoxical results reflect important interactions and potential conflicts between the use of the three levers. While divestment and shareholder engagement are mostly incompatible, our framework allows us to bring out a more nuanced set of interactions in the context of public investors’ strategic choices. Third, we show that, while the investment strategy is potentially impactful via the modalities of the portfolio and shareholder engagement, that impact is limited, and hardly commensurate with the size of their portfolio: while decarbonizing a portfolio is easy, having an actual impact on climate change as an investor is more difficult. Finally, we suggest that the impact of public investment funds is potentially largest through moral leadership. Large public investors can change the moral cursor by communicating their perspective on what is an acceptable investment and what is not. For example, by divesting from carbon intensive firms, public investors signal that these investments are morally questionable. Despite its crucial role the nature of this channel makes actual impact elusive and hard to quantify, meriting much more attention from empirical researchers.

Download the PDF version of this document

- Published on 05/06/2022

- 40 pages

- EN

- PDF (1.16 MB)

Updated on: 05/06/2022 12:22