Banque de France Bulletin no. 228: Article 1 CO2 emissions embodied in international trade

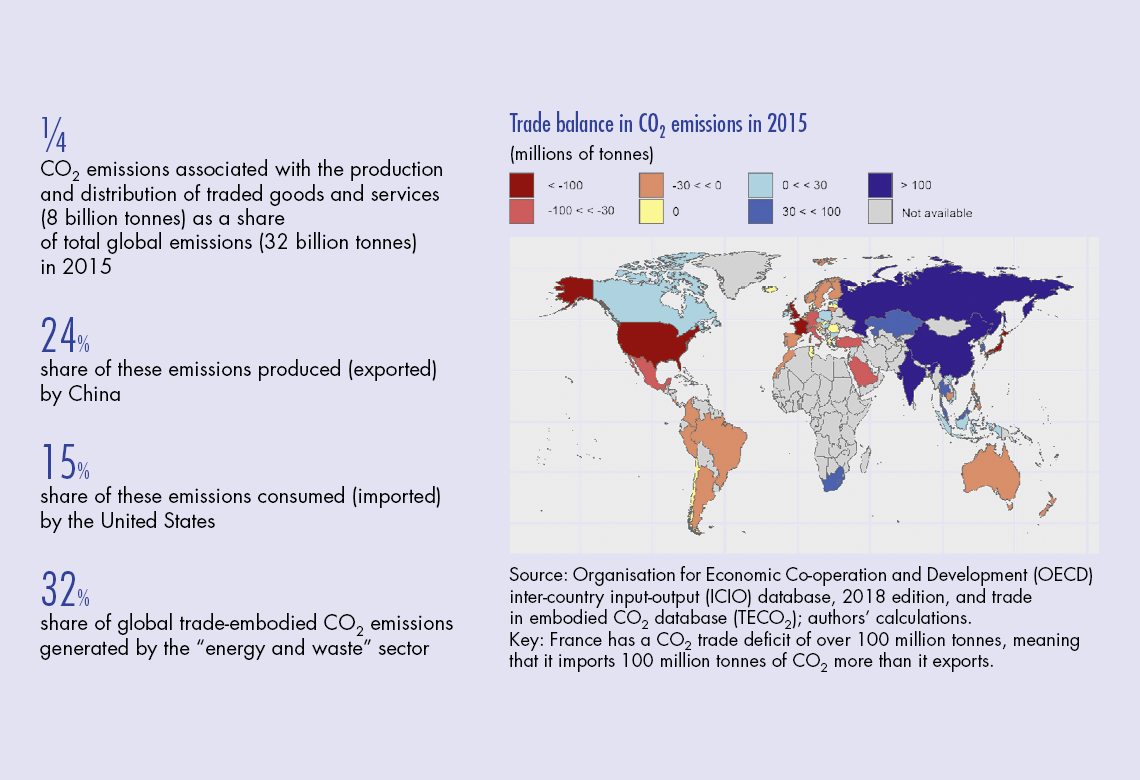

This article examines international trade from the perspective of the carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions generated by the production and distribution of traded goods and services. It takes account of both the CO2 produced within a country’s national territory via its domestic output, and those emissions embodied in its exports or imports. China, for example, is a net exporter of CO2 emissions while the United States is a net importer. More generally, advanced economies consume more CO2 than they emit, while the opposite is true for emerging economies or commodity producers. These divergences are mainly attributable to the sectoral composition of countries’ trade flows. Other factors that influence a country’s CO2 emissions are its scale (economic or population size), the emissions efficiency of its productive apparatus, and the degree to which it is integrated into global value chains.

This article examines international trade from the perspective of the carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions generated by the production and distribution of traded goods and services, rather than from the standard monetary value-based perspective. It takes account of the CO2 emitted along the entire chain of production and distribution of exports and imports.

CO2 emissions have become the main target of the climate agreements signed to limit global warming. The central goal of the Paris Agreement, for example, is to keep the global temperature rise this century to below 2°C, by limiting and then reducing individual countries’ greenhouse gas emissions.

The main statistical measure taken into account in these agreements is the emissions produced within a country’s national territory, which are linked, among other things, to the domestic output of goods and services. This measure differs from the real carbon footprint generated by a country’s final demand – in other words by its standard of living. More specifically, it takes account of the emissions caused by the country’s production of exports, which are in fact consumed abroad, but fails to take into account the emissions generated abroad by the imports it consumes domestically. As a result, national emissions do not provide an accurate picture of a country’s actual carbon footprint since a portion of its output is exported, and a portion of its demand is satisfied by imports (David and Caldeira 2010).

The emissions embodied in trade (around 8 billion tonnes in 2015) account for a quarter of total global emissions (approximately 32 billion tonnes). Thus, China’s total domestic emissions (9.1 billion tonnes in 2015) differ from its actual carbon footprint (8 billion tonnes) by the amount of its CO2 trade surplus (1.1 billion tonnes). This gap reflects the fact that a large share of the CO2 produced in China goes towards satisfying foreign demand. Conversely, the United States’ CO2 trade deficit (–0.7 billion tonnes) needs to be added to its total domestic emissions (5.1 billion tonnes) in order to determine its total footprint (5.8 billion tonnes). More generally, advanced countries are net importers of CO2 emissions, whereas emerging or commodity-producing countries are net exporters.

These gaps are influenced by the sectoral composition of each country’s trade flows. The four most polluting sectors are responsible for more than three quarters of the total emissions embodied in global trade. As a result, countries specialising in these sectors or using them intensively as…

Download the PDF version of this document

- Published on 03/30/2020

- 16 pages

- EN

- PDF (1.03 MB)

Bulletin Banque de France 228

Updated on: 04/03/2020 10:07