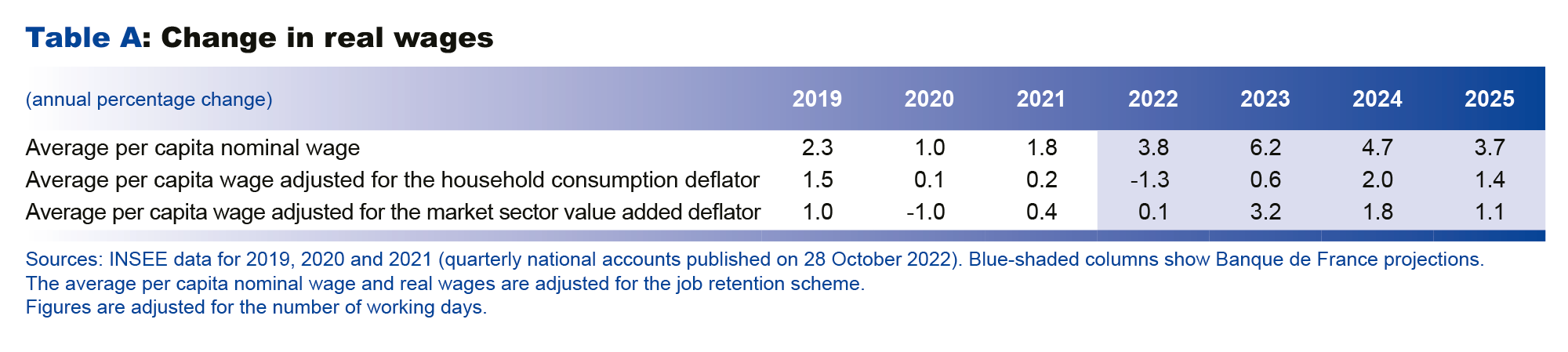

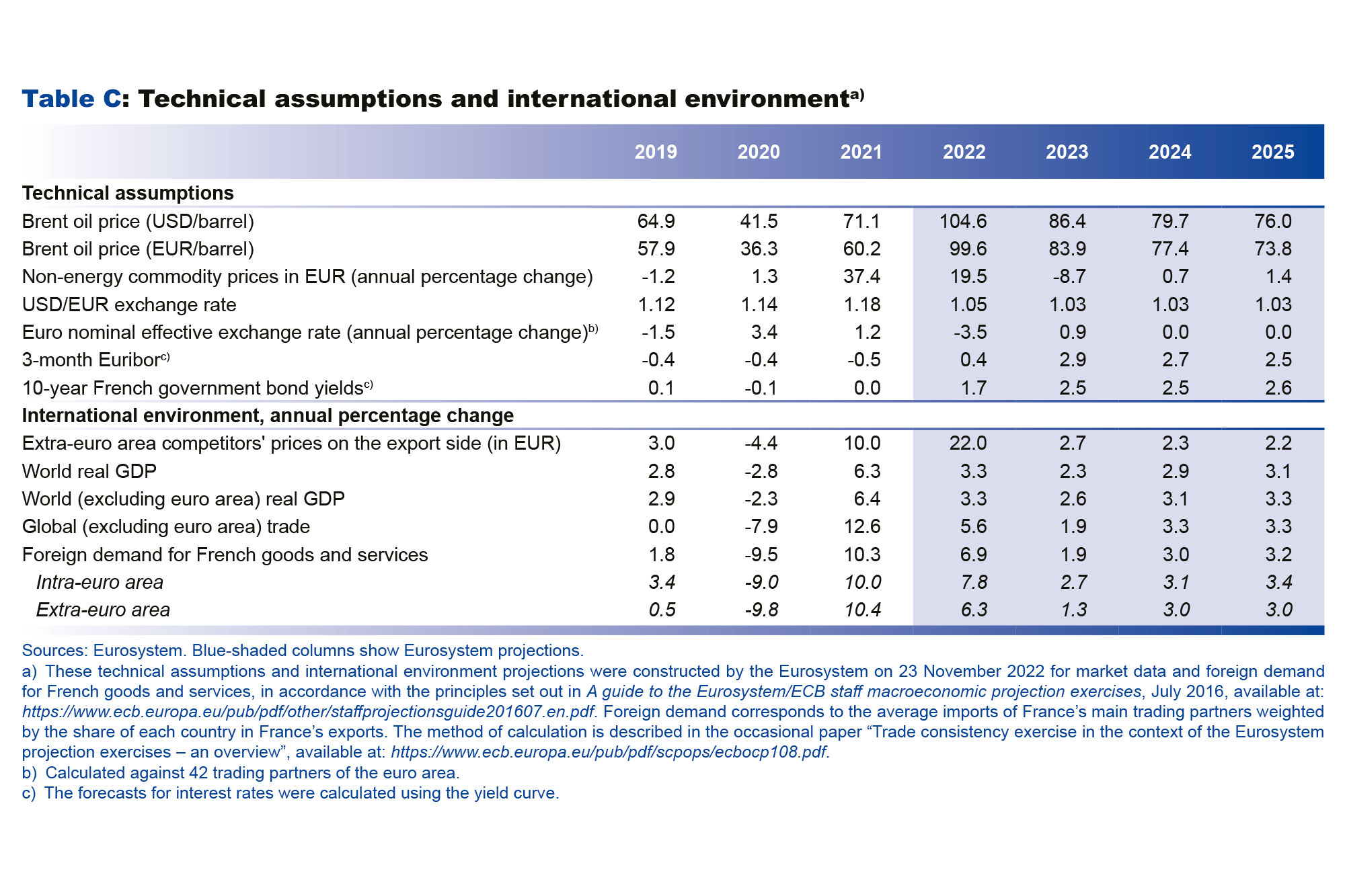

With the exception of most commodity prices, which have eased since September and are largely being cushioned for French households by the price shield on energy prices, the international and financial environment is slightly more unfavourable to growth than in our September projections. The Eurosystem assumptions, based on futures prices and with a cut-off date of 23 November 2022, are for a slightly faster decline in oil prices and significantly lower natural gas prices over the entire period than in the previous quarter’s projections (see Chart 1). Demand from France’s trading partners is expected to deteriorate markedly, and its growth rate has been revised down by 0.4 percentage point and 0.2 percentage point respectively for 2023 and 2024 compared with our September baseline scenario. The euro nominal effective exchange rate is projected to be around 3½% higher in 2023 and 2024 than in our September assumptions. Last, the rise in short and long-term interest rates is predicted to be more pronounced: based on market expectations, the three-month rate is expected to be nearly 100 basis points higher in 2023 than previously assumed in September.

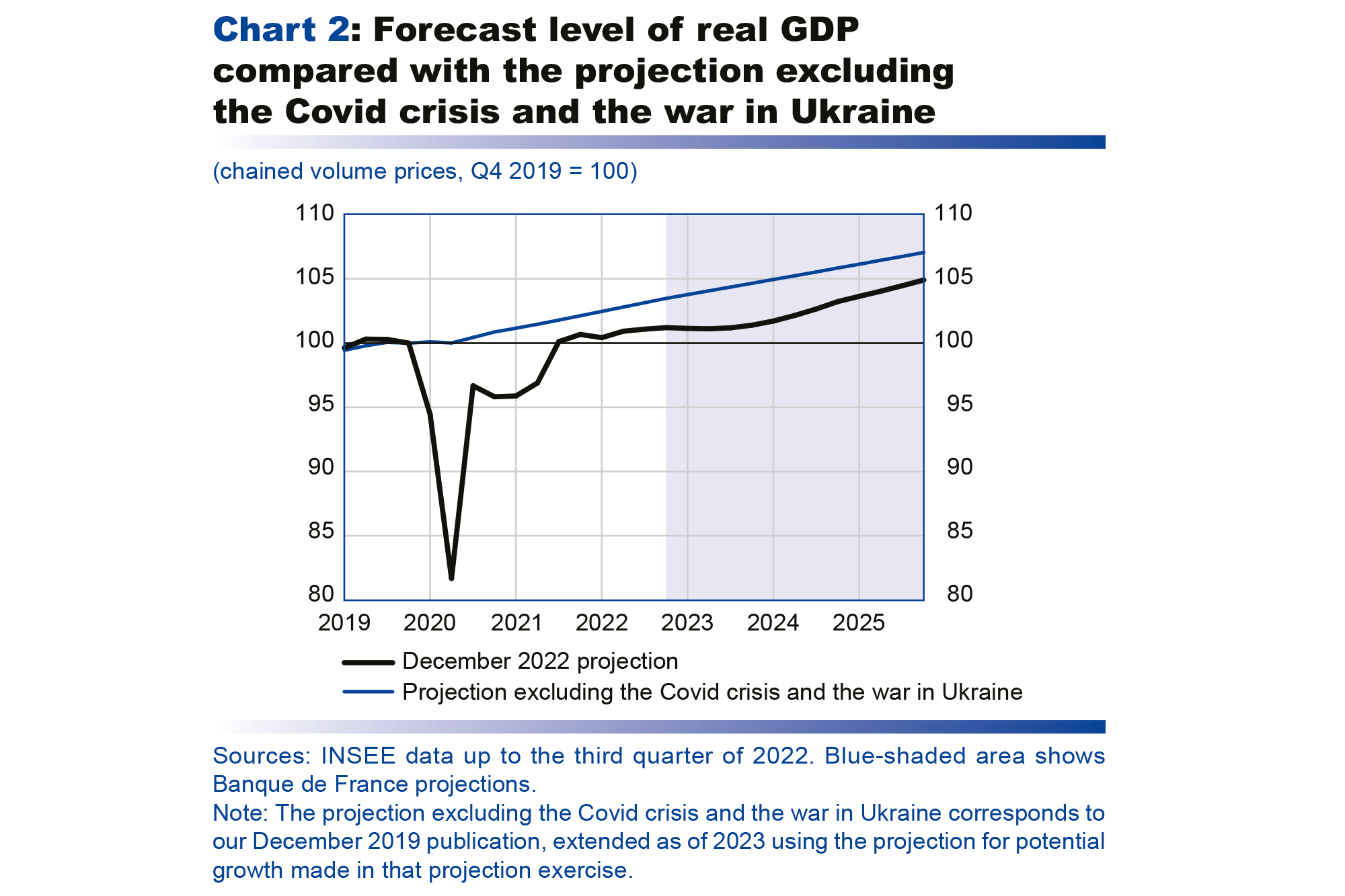

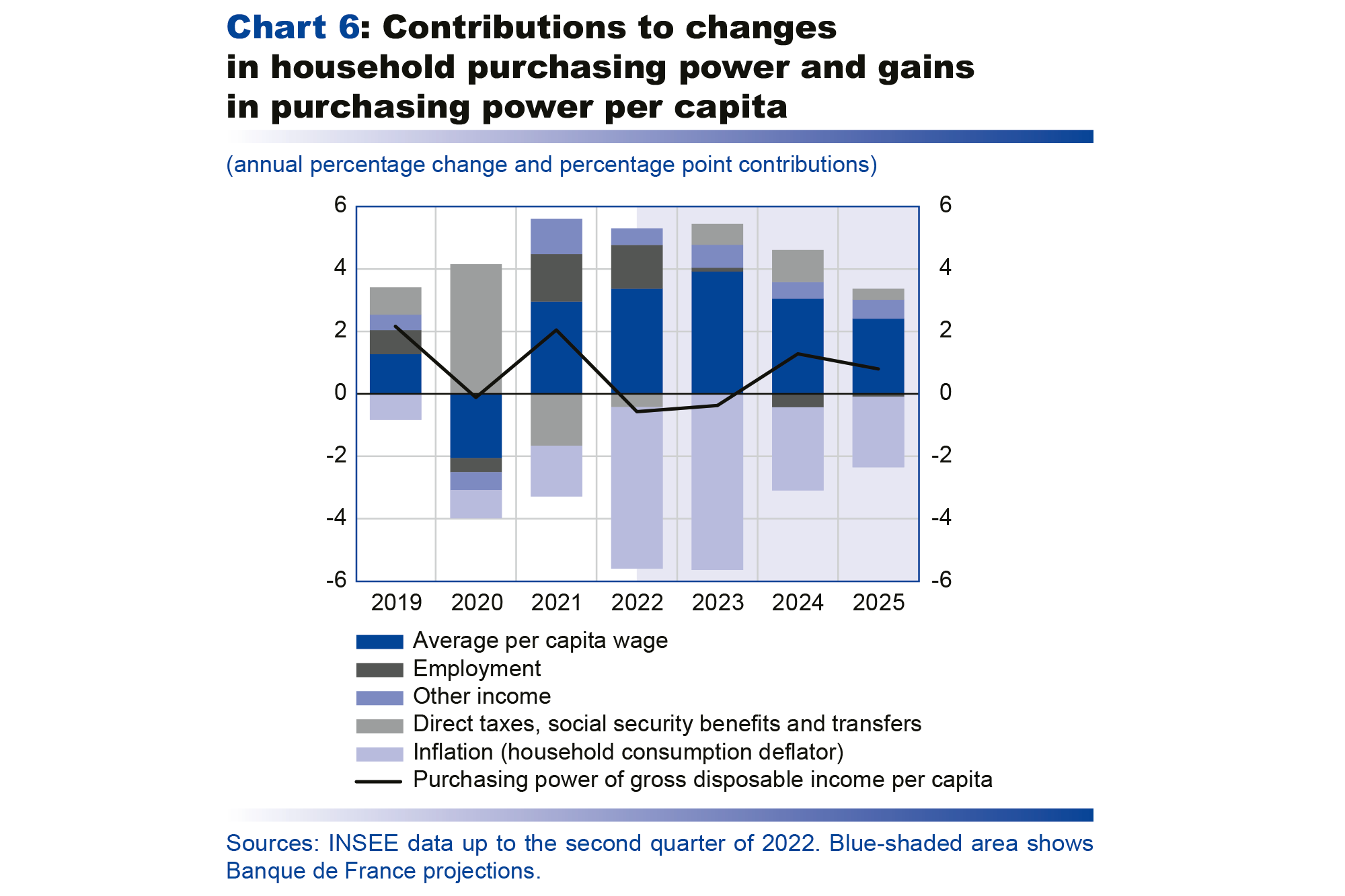

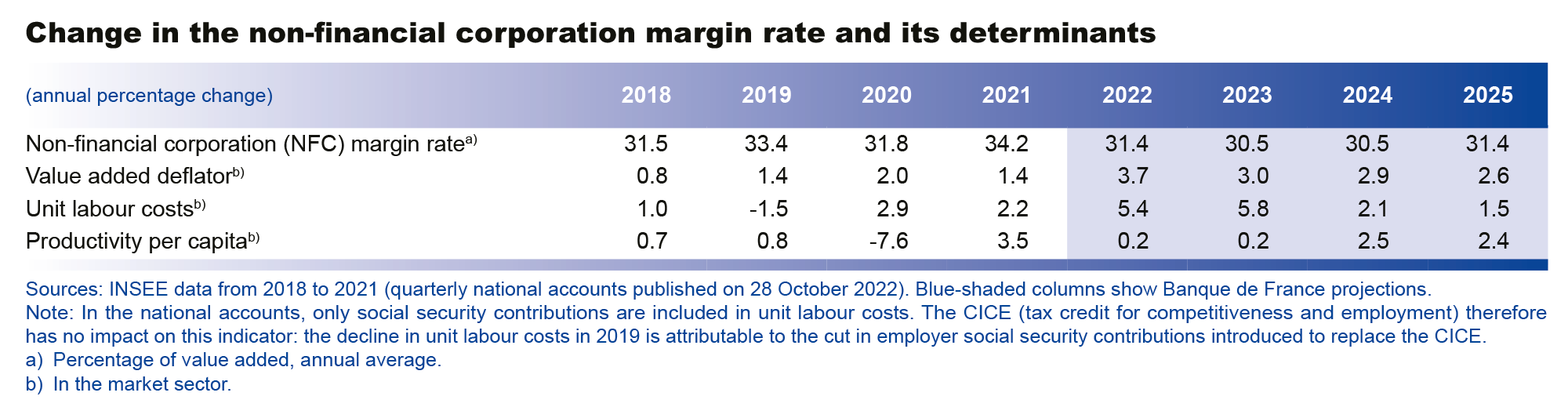

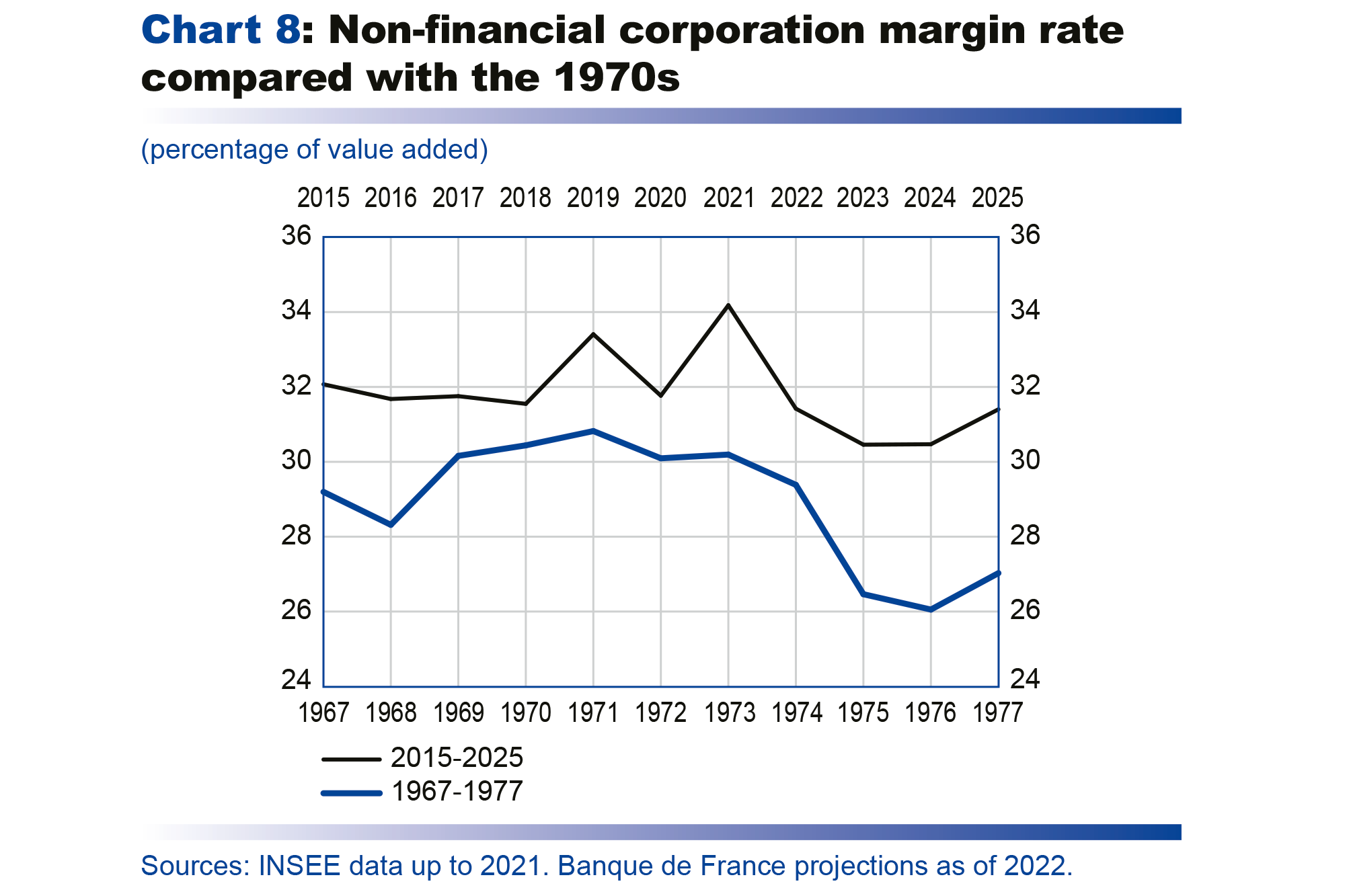

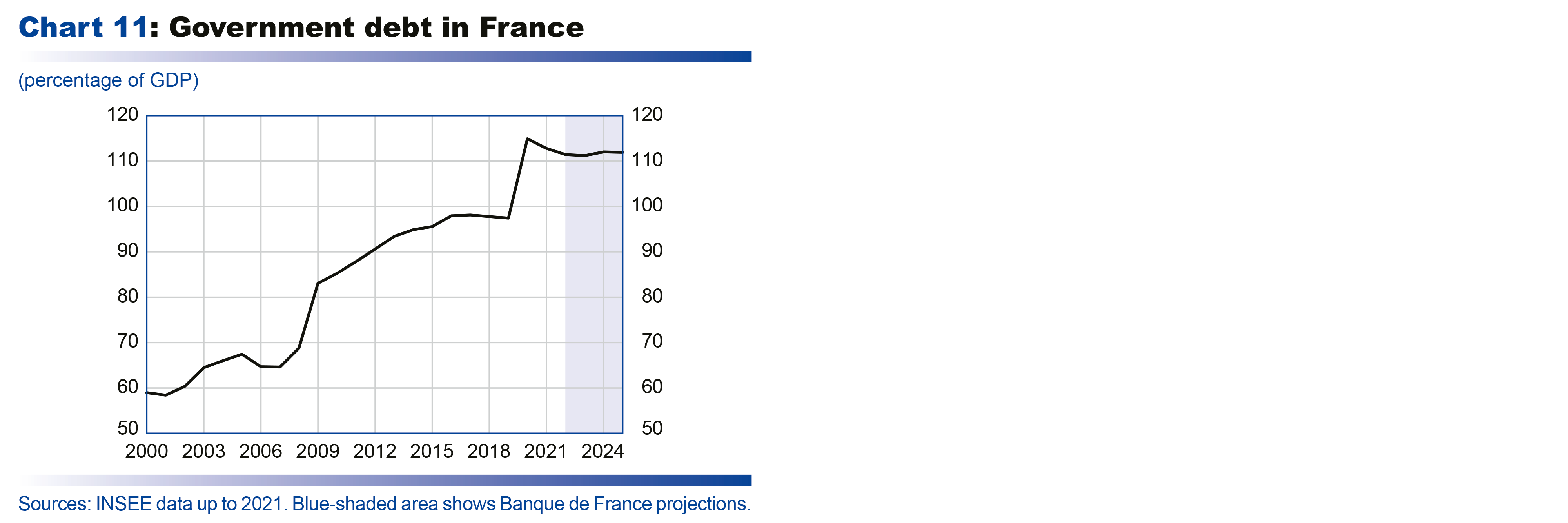

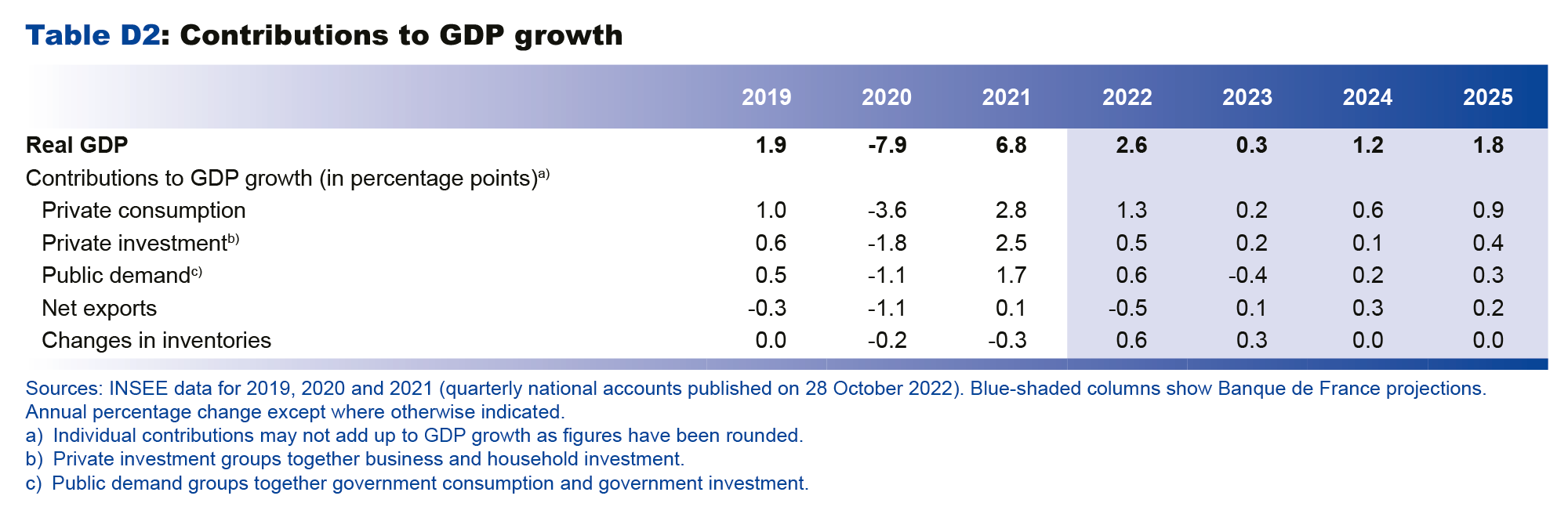

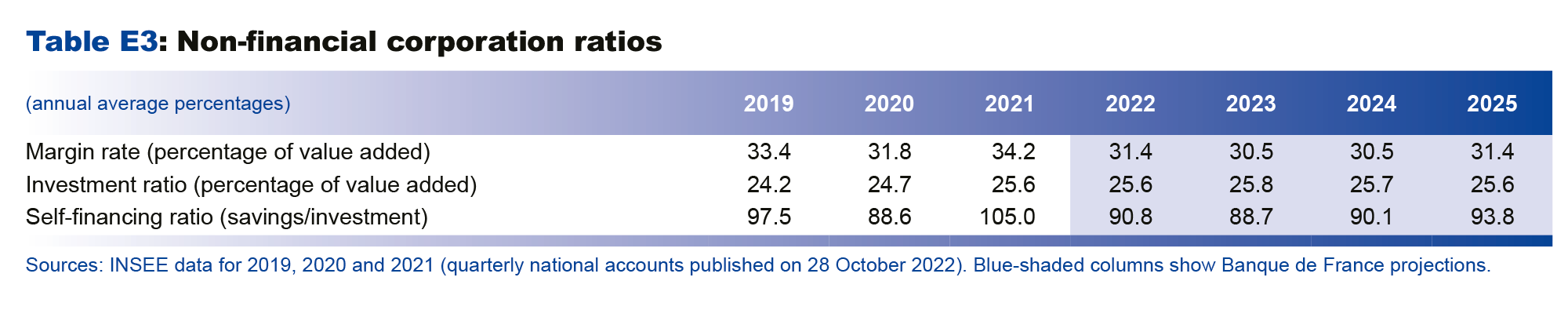

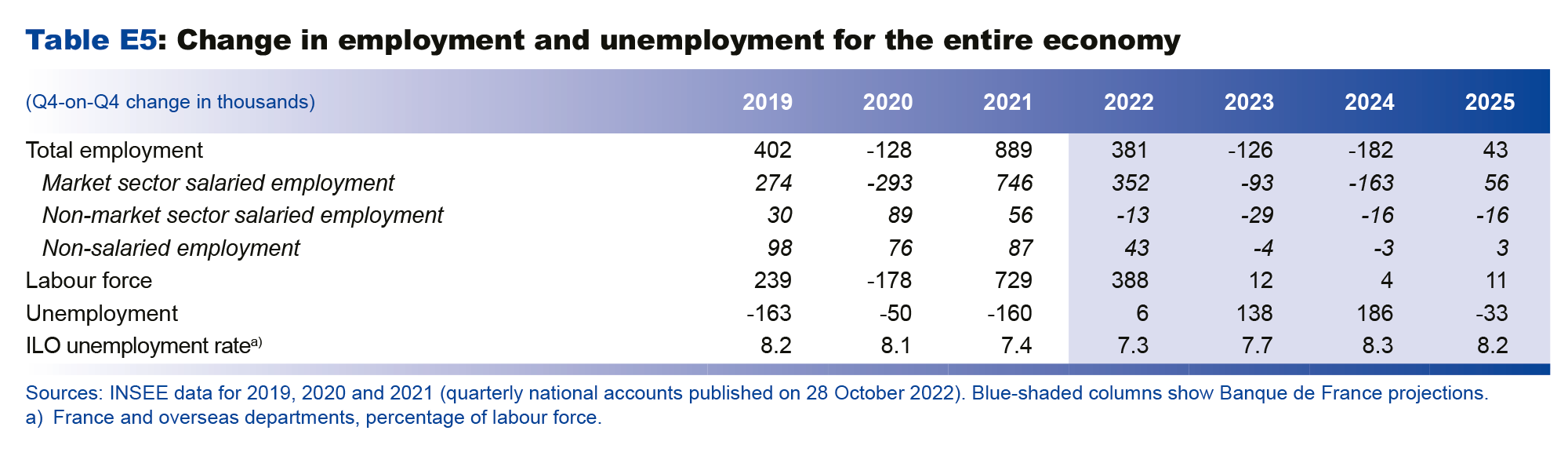

Lower foreign demand for French goods and services, the stronger appreciation of the euro and the bigger rise in interest rates, combined with the upward revisions to our inflation forecasts, lead us to predict a slightly stronger slowdown in 2023 with annual growth of 0.3%. This projection is surrounded by significant uncertainty: as a result we are providing a confidence interval for this 2023 growth forecast of -0.3% to 0.8%. The interval has been quantified by applying a probabilistic approach to simulations made using our projection model. This means that a recession cannot be ruled out, but that it should be temporary and limited. Despite substantial government support for household purchasing power, all components of domestic demand should be hit by the “external tax” shock to income: the dissemination of this shock to general prices is expected to lead to high inflation and hence purchasing power losses which should drag on consumption; the shock should also squeeze corporate margins, causing businesses to scale back investments and jobs. Given the deterioration in the international environment, businesses are not expected to be able to offset this decline through external trade.

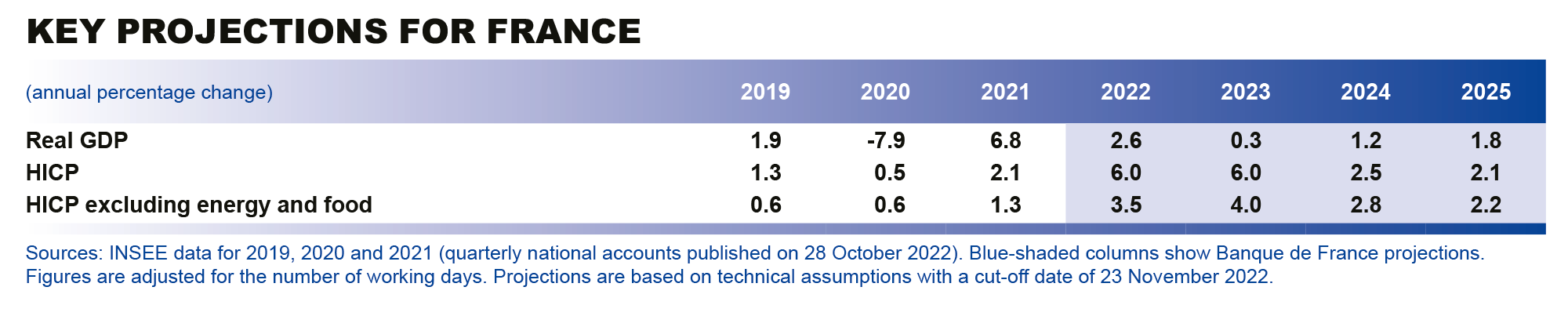

Once the pressures on commodity prices and energy supplies have passed their peak, the economy should start to recover again in 2024, albeit at a lower rate than that anticipated in September, with annual GDP growth of 1.2%. This expansion should then gain traction in 2025, with growth of 1.8%, and the level of GDP should gradually return towards its pre-Covid trend, while still remaining substantially below it by the end of the projection horizon (see Chart 2 above).

The external shock to terms of trade equates to an ex ante “external tax” of at least 1.5% GDP on the French economy in 2022

As a result of the war in Ukraine, the French economy is experiencing an external tax shock, linked to upward pressures on the prices of energy and other imported commodities, followed by a gradual normalisation.

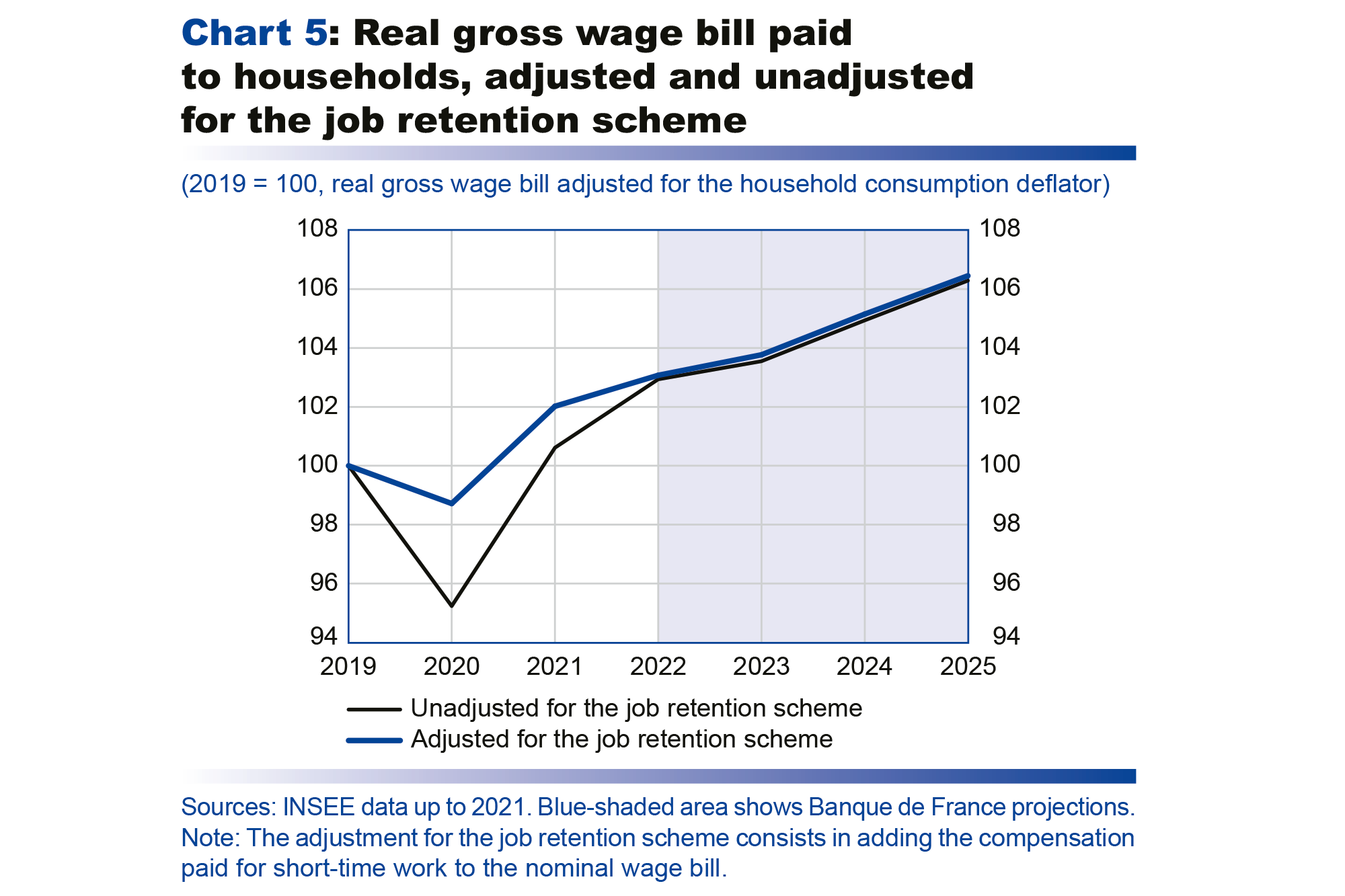

These fluctuations in global prices have triggered a major transfer of wealth from countries that are net importers of commodities to those that are net exporters. For European economies, this represents a shock to real incomes that is eroding household purchasing power and corporate margins. It is also damaging the competitiveness of those exporting firms that have seen the biggest energy price jumps. In total, this shock and the associated inflation spike are expected to have a non-negligible negative impact on growth for at least several quarters.

There are several ways of measuring this external tax on wealth. In the context of these projections, we can use the most macroeconomic approach and measure the “shock to terms of trade”, calculated as the difference between the relative rates of growth of the import and export deflators, weighted by the share of these flows in nominal GDP. For the full year 2022, the terms-of-trade shock is projected to amount to around 1.5% of GDP in France. This is slightly smaller than in the other large euro area economies: France is less dependent on fossil fuels, and industry accounts for a smaller share of its economy (compared with Germany or Italy), which mitigates the import price shocks. France is also benefiting from robust export prices in the sea transport and agricultural sectors. Historically speaking, the terms-of-trade shock in 2022 is the second largest that France has experienced since the first oil shock in 1974.

There are numerous uncertainties looming over 2023. If world commodity prices fall more than expected with the global economic slowdown, the terms-of-trade shock could be smaller than predicted in 2023. On the other hand, it could remain significant if the rebuilding of European gas stocks keeps gas prices very high over winter 2023-24.

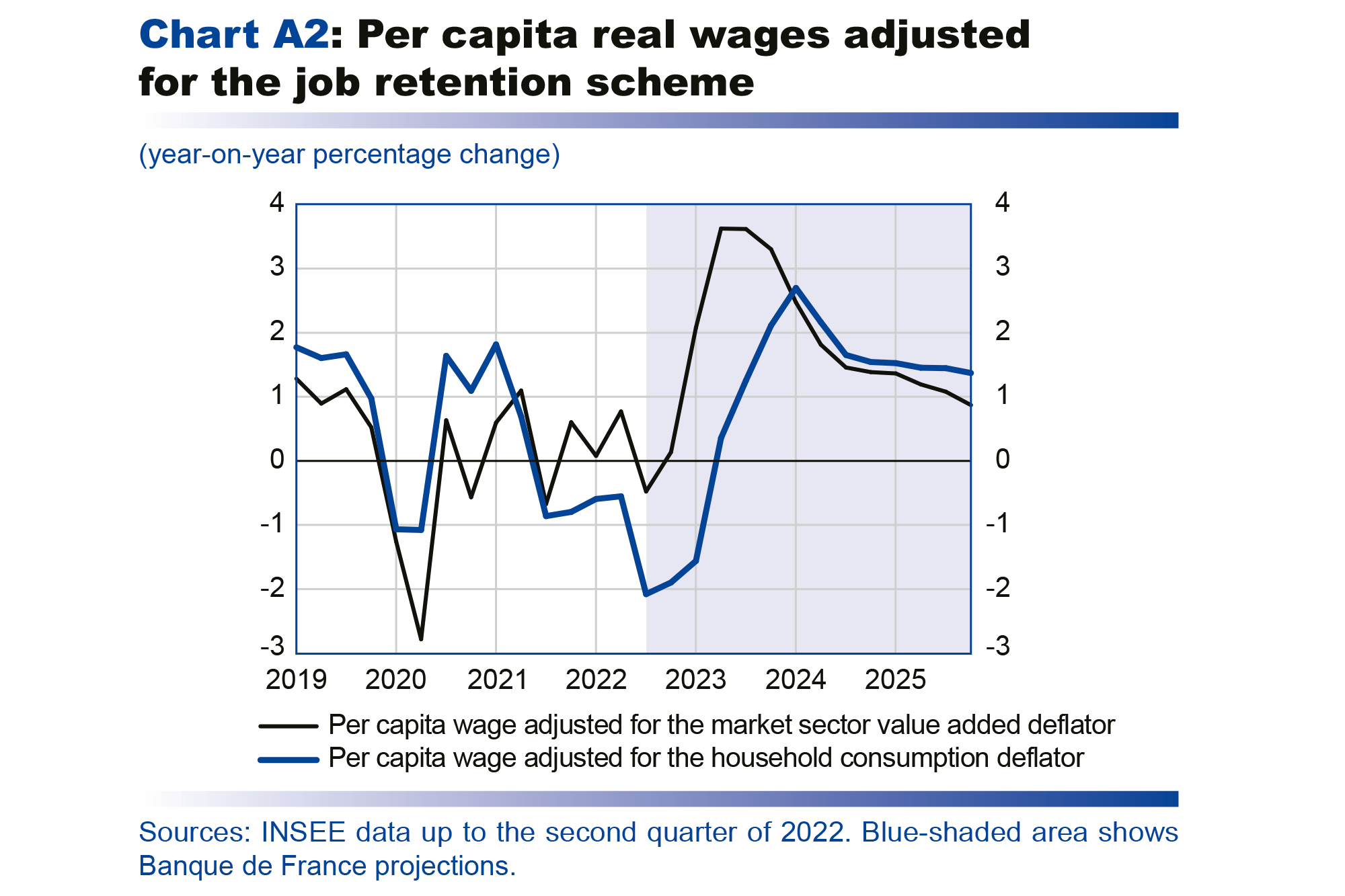

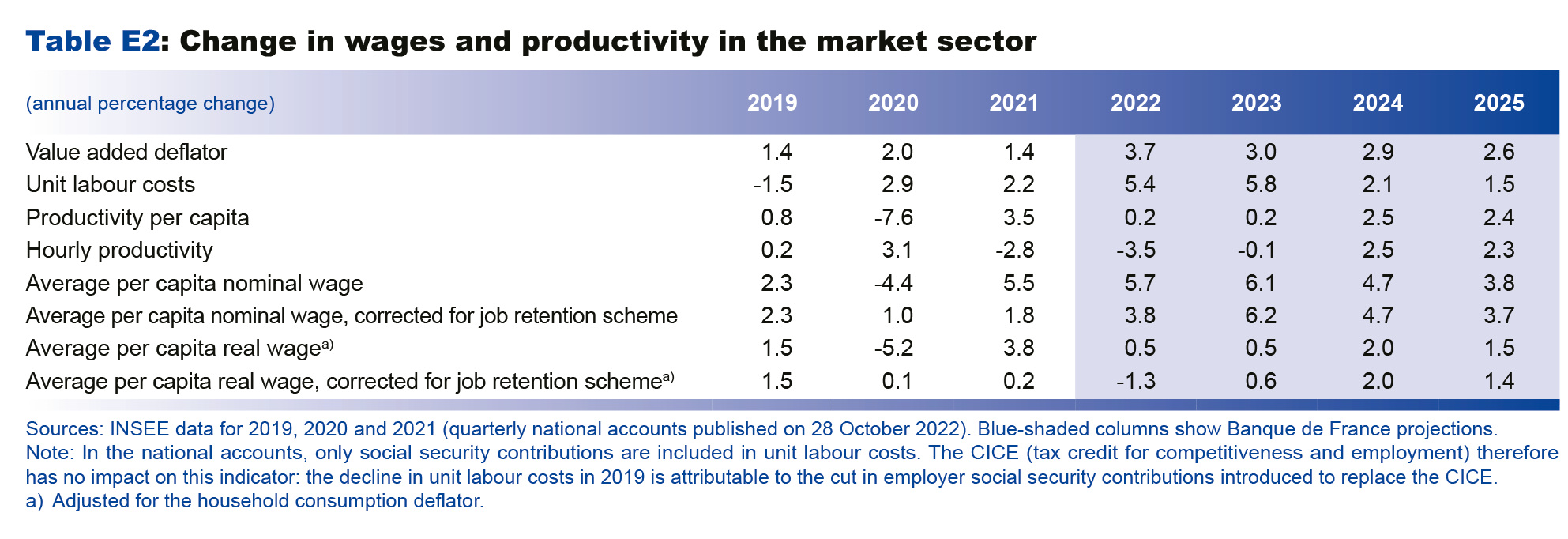

Ultimately, the ex post impact of the external tax shock depends on both the fiscal policy response and a series of macroeconomic adjustments, including the extent to which businesses pass on higher costs to selling prices, and the response of wages to inflation. Our macroeconomic projections present the macroeconomic second-round effects of the distribution of the external tax across employees and businesses on the one hand (see Appendix A on the pass-through of the terms-of-trade shock to prices and wages), and across private sector agents and the general government sector on the other (see infra, section on government finances).

Inflation is expected to peak in the first half of 2023 and should then subside, coming back towards 2% at the end of 2024 and in 2025

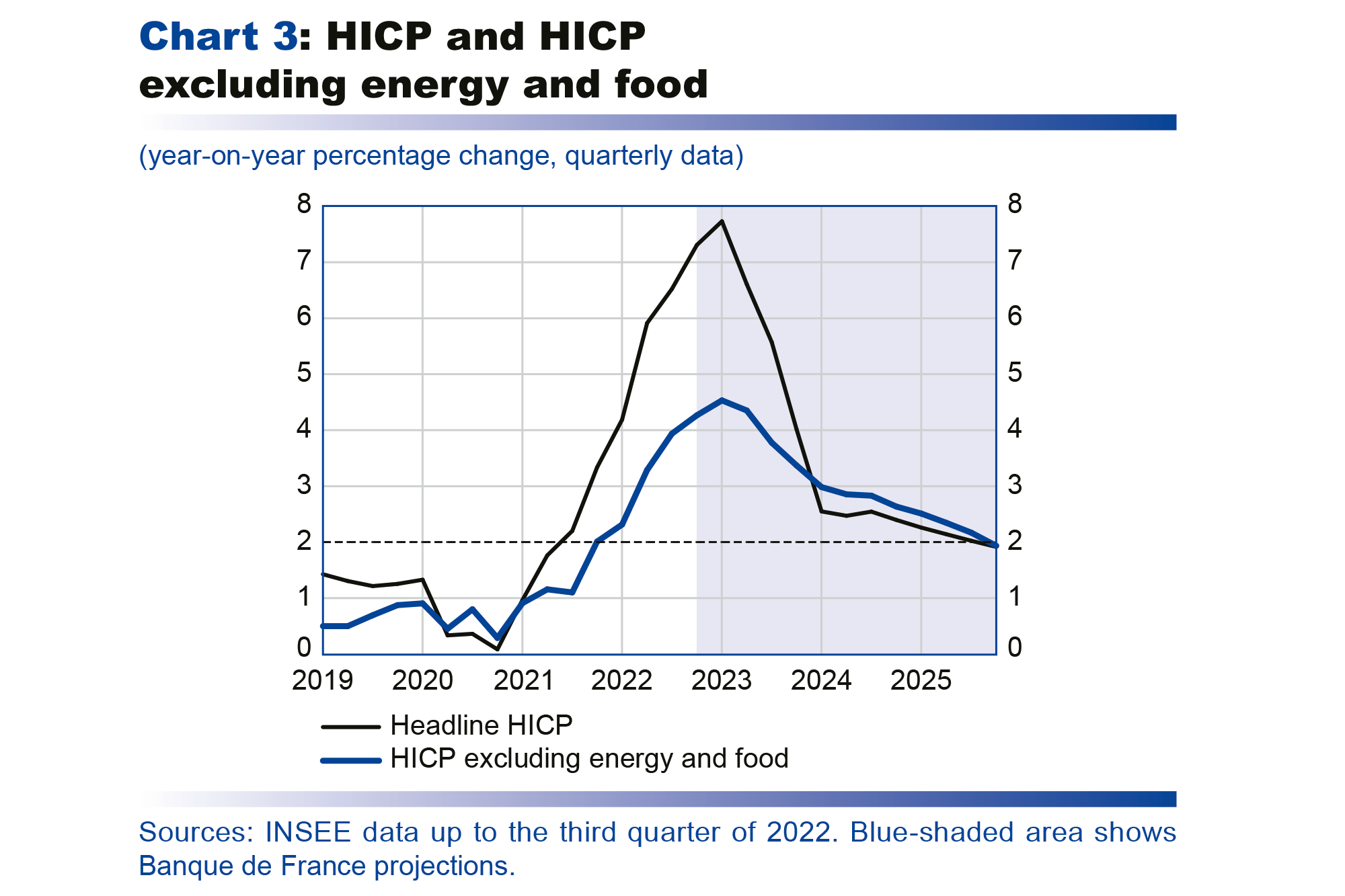

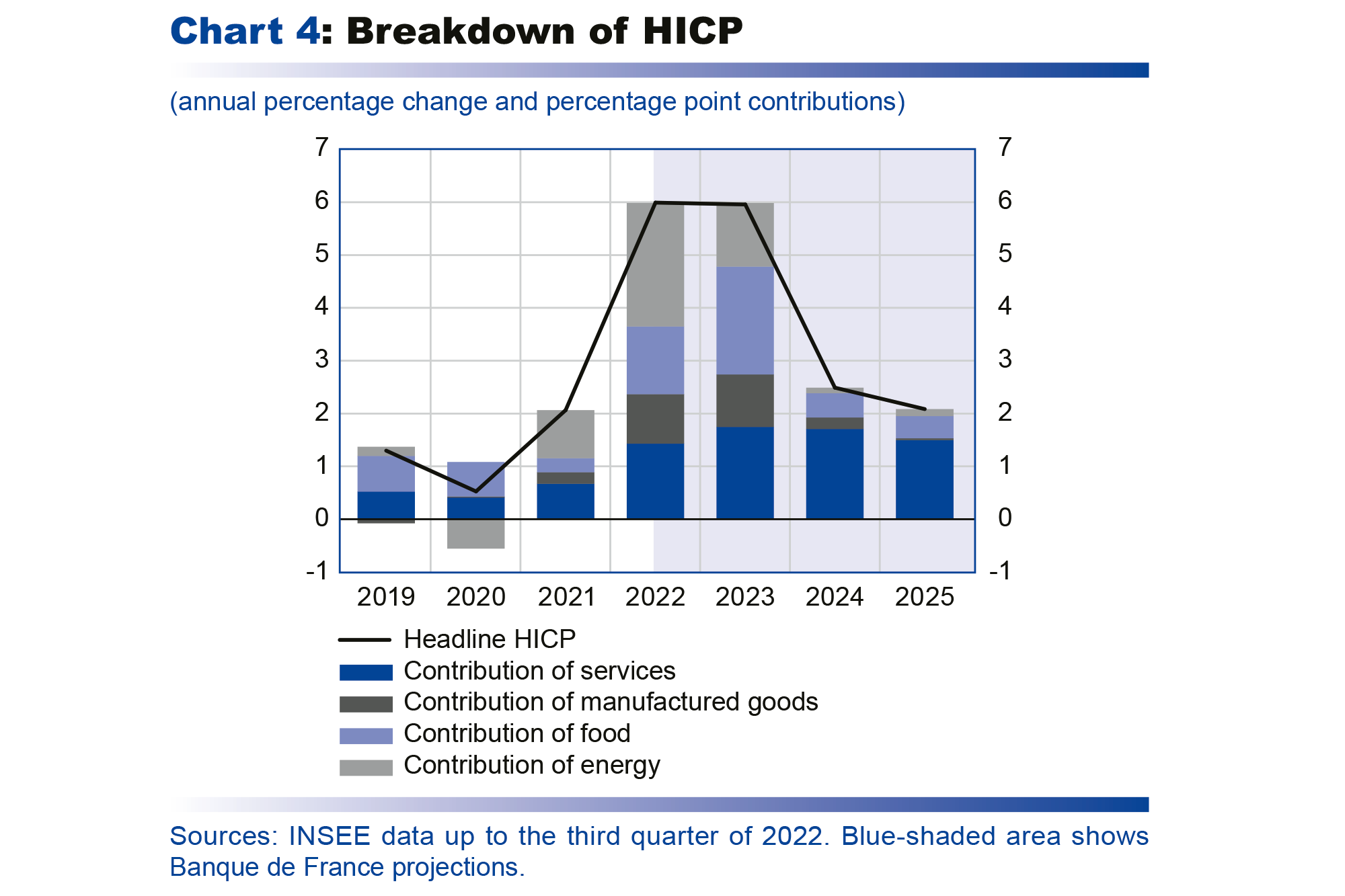

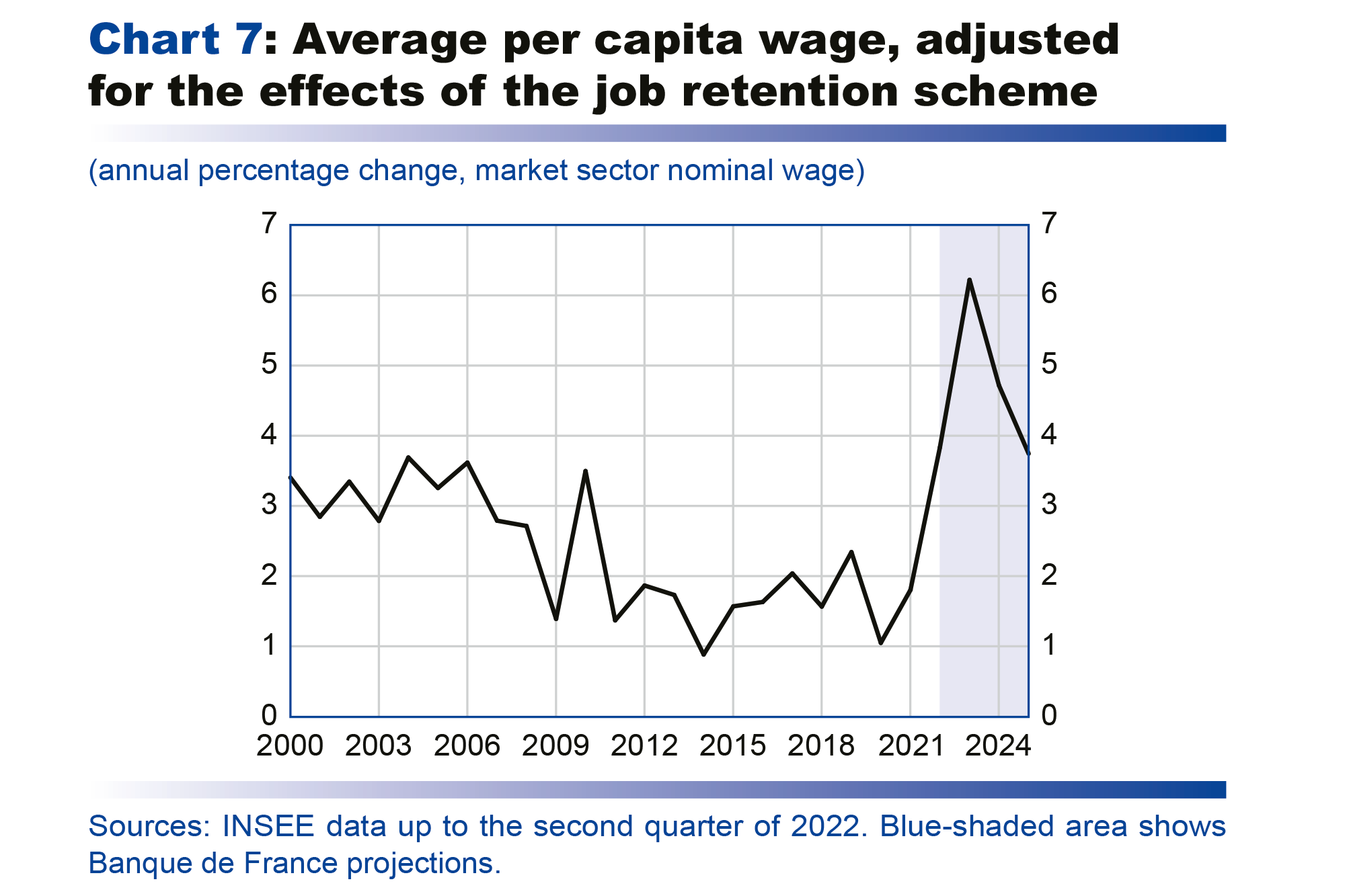

Inflation as measured by the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) has continued to rise in recent months, reaching 7.1% in November (see Chart 3 below). The upward pressures on commodity prices that emerged during the post-Covid recovery in 2021 have been amplified in 2022 by the war in Ukraine, fuelling a historic surge in energy prices. Moreover, these shocks have gradually fed through to the other components of inflation which are all currently rising at well above long-term average rates. Food prices have soared on the back of higher production costs and supply shortages for certain foodstuffs, with the result that food inflation has been above 10% since October. Manufactured goods inflation has also exceeded 5% since November, buoyed by robust growth in production costs at the start of the year which is being passed through with a lag to consumer prices. That said, industrial production prices have started to lose momentum in the second half, raising hopes that consumer prices of manufactured goods will moderate going forward. Services inflation has accelerated but has been more muted up till now (below 4% these last months); it is primarily being fuelled by wages, as a result of the inflation-indexation of the salaire minimum interprofessionnel de croissance (SMIC – the French minimum wage) and industry-level negotiated pay rises (see infra, section on nominal wages).

In 2022, therefore, headline inflation is expected to be 6.0% in annual average terms (underlying inflation, defined as inflation excluding energy and food, is seen at 3.5%). The main inflationary shock to the French economy this year is the surge in global energy prices. Admittedly, the pass-through of this shock to retail energy prices has been limited in 2022 thanks notably to the price shield, but it is being passed through indirectly, with a lag of a few months, to the other inflation components (food and manufactured goods) via the knock-on effects of higher production costs.

In 2023, headline inflation should remain at 6.0% in annual average terms, but is projected to follow a very different trajectory over the year, i.e. a peak in the first half and then a gradual but clear decline over the remainder of the year. In year-on-year terms, inflation is expected to subside to 4.0% in the fourth quarter of 2023, from 7.3% at the end of 2022. Its various components should also follow different paths. The end of the fuel rebate and the rise, albeit limited, in household electricity and gas prices at the start of 2023 should push up the energy component again, although to a more moderate extent than in 2022. Food and manufactured goods inflation is predicted to ease only gradually, as the ongoing pass-through of production costs fuels some persistent price growth. Services inflation, for its part, should be buoyed by the increase in nominal wages, but it should be kept in check by the 3.5% cap placed on the rent reference index between July 2022 and June 2023.

In 2024, with the easing of energy and food commodity prices currently factored in by futures markets, all components of inflation should fall, except for services prices which should be supported by the lagged adjustment of wages and rents (see Chart 4). Headline inflation is thus projected to be 2.5% in annual average terms and 2.4% year-on-year at the end of the year.