Working Paper Series no. 743: Banks' climate commitments and credit to brown industries: new evidence for France

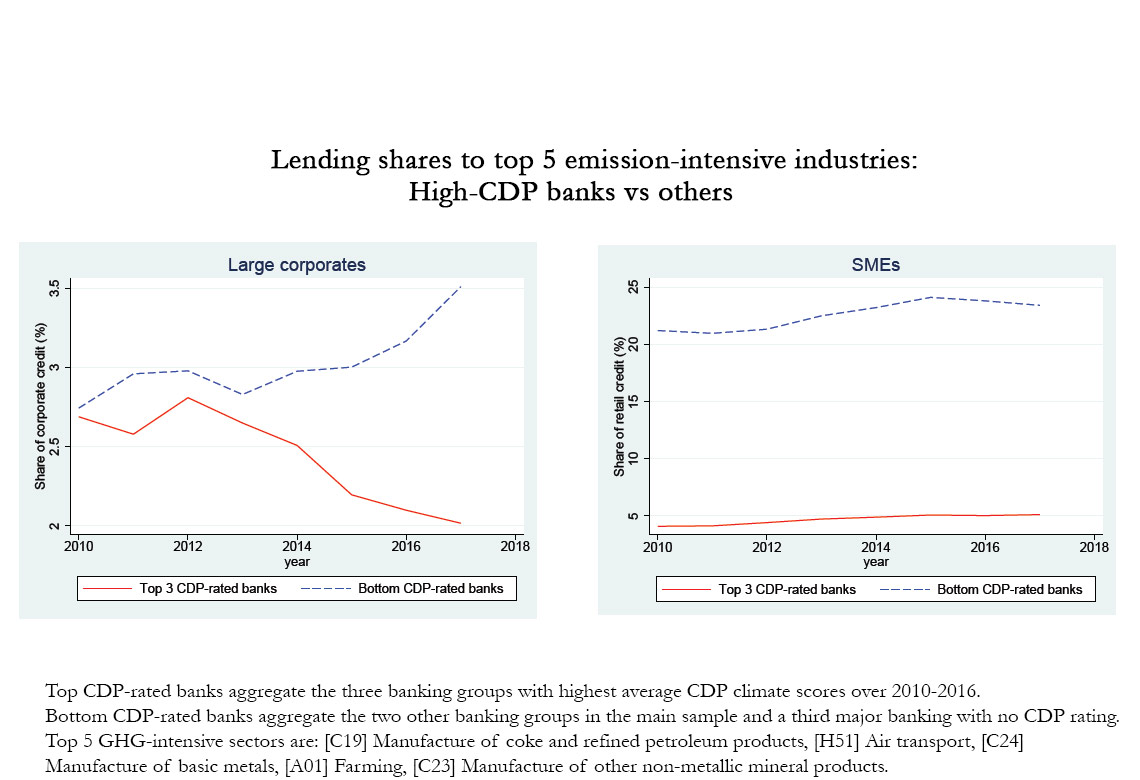

In this paper, I investigate whether and how banks align green words with deeds in terms of credit allocation across more or less carbon-intensive industries in France. I use a rich dataset of bank credit exposures across some fifty industries and two size classes of borrowing firms for the main banking groups operating in France, which I merge with information on industries' greenhouse gas emission intensities and a score for banks' self-reported climate-related commitments over 2010-2017. I find evidence that higher levels of self-reported climate commitments by banks are associated with less lending to large corporates in the five brownest industries. However, lending to SMEs across more or less carbon-intensive industries remained unrelated to banks' commitments to green their business. Since SMEs are not required to report on their carbon emissions, while large firms are, these findings suggest that devising an appropriate carbon reporting framework for small firms is likely to enhance the decarbonization of bank lending.

Effectively addressing the many challenges raised by the ongoing climate change will require to fund huge amounts of public and private investment over the next two decades. According to recent estimates, some $6,000 bns of additional green investment would be needed yearly until 2030 at the global level, while only some $400 bns yearly are actually invested so far. In France alone, which accounts for some 1.6% of world carbon emissions, additional funding needs would amount to some EUR 60 bns yearly, but half as much were invested in 2015. Over the last decade, and even more since the Paris Accord of 2015, a number of large banks, including major French groups, have publicly acknowledged they have a role to play in addressing this problem. Consequently, many banking groups have committed to greening their business and signed international statements or even boasted their planned exit out of some carbon-intensive industries. Are these statements by large banks mere greenwashing or is bank credit really being reallocated out of brown firms and brown industries? Considering conflicting recent reports by environmental ONGs, the jury still stands out.

In this paper, I investigate whether banks which claim to be green decrease relatively more their loans to the most carbon-intensive (or ``brownest'') domestic sectors. For this purpose, I merge information on industries' greenhouse gas (GHG) emission intensities, green ratings of major banking groups that reflect their self-reported climate commitments, and last but not least, the universe of almost all bilateral bank-firm credit exposures in France over 2010-2017. This rich credit dataset allows me to sort bank credit exposures to each industry according to the size of borrowing firms, in order to separately analyze what drives lending to large corporations vs lending to small firms (SMEs). I find robust evidence in support of a more active reallocation of credit out of fossil-based sectors when banks self-report as more committed to climate change mitigation and adaptation, as higher climate performance scores are associated with less lending to large firms in the five most emission-intensive sectors. However, there is no sign of any rebalancing of more committed banks' credit across brown vs green industries when it comes to SME lending. This lack of interest in the carbon intensity of retail lending may contribute to explaining while, in additional tests, I cannot find any conclusive evidence of an effect of domestic banks' climate commitments on industry-level GHG emission growth in France over this period of time.

Two important policy implications can be drawn from this study. First, the link I highlight between sector-level carbon intensity, banks' greening and bank lending to large firms suggests that the available industry-level information on GHG emissions is relevant for banks, or at least is a good proxy of the information that is used by banks. This may be a concern as regulators would prefer to incentivize banks to direct credit to the ``greenest'' corporations within brown industries, i.e. the firms that invest heavily in greening their dirty production process, rather than pushing banks to cut funding to an industry altogether. Second, the results provide support to recent calls for an extension of mandatory carbon disclosure to SMEs (CESE, 2018). However, most SMEs are by themselves not in capacity to comply with new rules imposing a detailed reporting on carbon emissions. To avoid important mis- or under-reporting, the implementation of such an extension of disclosure requirements to small business would therefore require the design of appropriate disclosure framework as well as specific accompanying measures.

Download the PDF version of this document

- Published on 11/29/2019

- 36 pages

- EN

- PDF (625.34 KB)

Updated on: 12/03/2019 14:25