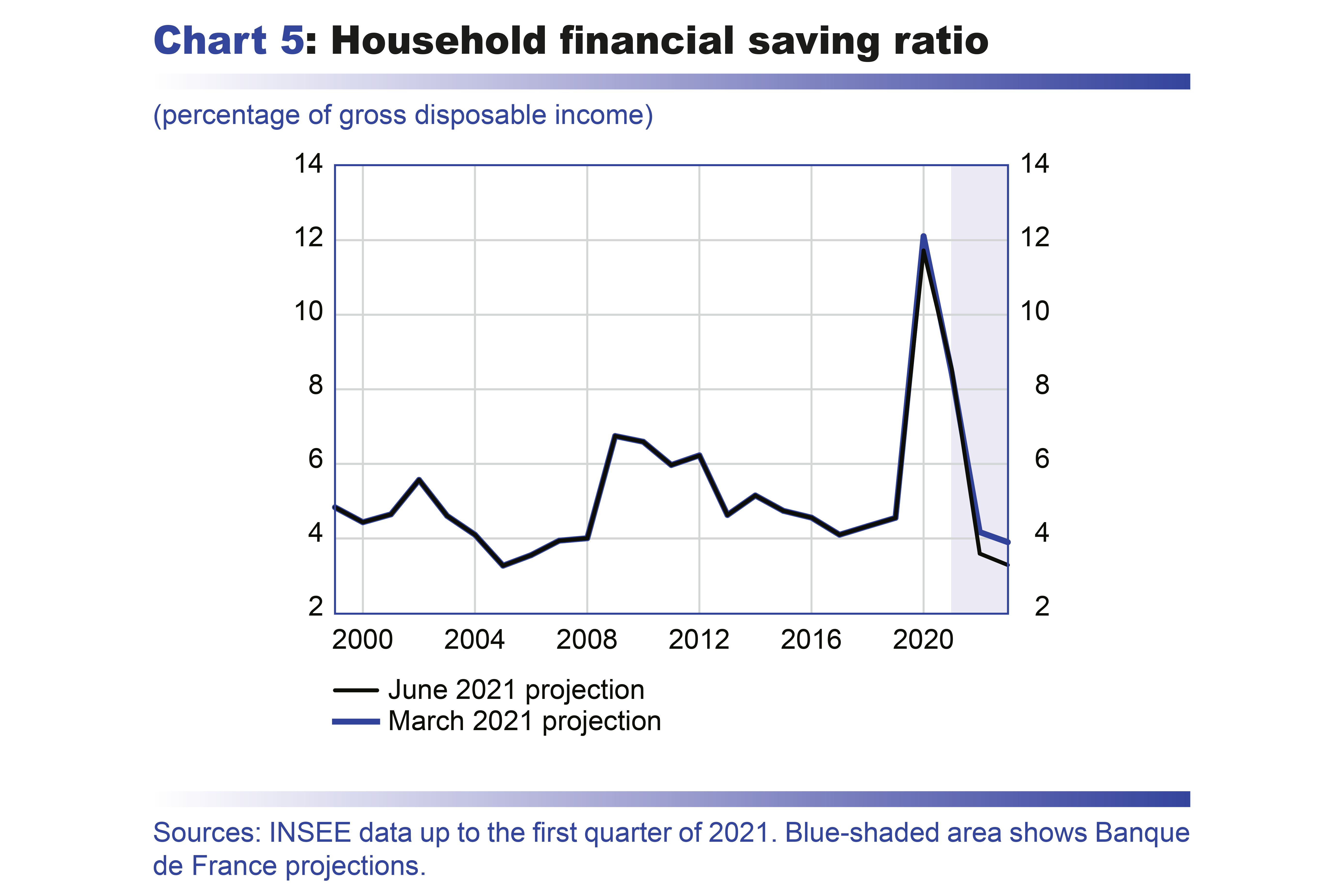

Since March 2020, households have built up a large amount of excess financial savings as a result of restrictions on consumption and investment. Excess financial savings are measured as the cumulative difference between observed or projected financial savings for each quarter and the level that would have been reached if household income and expenditure had continued to rise since end-2019 at the rate observed before the crisis. Household investment here refers to purchases of new housing and renovation expenditure but excludes purchases of existing housing, which are financial transactions between households and have no impact on their aggregate expenditure in national accounts.

Measured as a deviation from a non-crisis trend, these excess savings amounted to EUR 115 billion at end-2020 and are expected to continue rising to reach a peak of EUR 180 billion at end-2021. We break down (see chart) the excess financial savings into a consumption component and an investment component. The contribution of consumption (respectively investment) to these excess savings is estimated by comparing their observed and then projected trajectory to a counterfactual scenario where the household saving ratio (respectively the investment ratio) remains at its pre-crisis, fourth quarter 2019 level. According to this approach, the excess financial savings are mostly linked to under-consumption in 2020 and 2021 (to the tune of around 90%), with under-investment in 2020 accounting for around 10% of the excess financial savings.

With the rebound in household consumption, expected from the third quarter of 2021, and in household investment, the cumulative excess financial savings are expected to decline by about 20% in 2022-23 compared with their end-2021 peak. This baseline scenario is more favourable than that of our March forecast. In particular, household investment has been revised upwards significantly, based on the strength of recent economic indicators (housing starts and surveys in the construction and property development sectors). In addition, the distribution of the excess savings, which is weighted more towards the wealthiest households whose propensity to consume is rather low, could also support investment. All in all, in our baseline scenario, this translates into a full use of the component of the excess savings linked to 2020’s under-investment by 2023.

As this baseline scenario is characterised by a high degree of uncertainty about households’ propensity to spend the excess savings, our forecast is accompanied by two alternative scenarios. In these alternative scenarios, spending of the cumulative excess savings at end-2021 is twice as high (approximately 40%). We assume that this additional spending occurs only through consumption in the first scenario, and only through household investment in the second scenario.

In both cases, a two-fold increase in the use of excess financial savings would thus lead to a cumulative amount of additional GDP of around 0.3% over the 2021-23 period, with a concentrated effect during the period in which the additional spending occurs. GDP is temporarily higher when assumptions about household demand in the rebound period are more favourable. However, this demand is not permanently higher and occurs mainly during the “overspending” period, so that the level of activity in the medium term remains unchanged and GDP then returns to the level of the baseline projection in the scenarios studied.

These two scenarios nevertheless require that household behaviour be fairly atypical compared with historical trends. The first scenario assumes that the household saving ratio will sink to a level not seen since the 1990s, reaching a low point of around 13% in 2022. Such a level of consumption could come up against supply constraints and lead to a rise in imports. The second scenario assumes that the household investment ratio will reach its highest level in forty years, at nearly 10.5% of household disposable income, exceeding that seen in the 2006-07 boom. This investment ratio could also come up against supply constraints in the construction sector.