Working Paper Series no. 651: A Quantitative Easing Experiment

This paper presents experimental evidence that quantitative easing can be effective in raising bond prices even if bonds and cash are perfect substitutes and the path of interest rates is fixed. Despite knowing the fundamental value of bonds, participants in the experiment believed that bond prices would exceed this value when they knew that a central bank would buy a large fraction of the market in a quantitative easing operation. By contrast, there was no average deviation of prices from fundamentals when trading only occurred between participants themselves.

Quantitative easing (QE) is an unconventional monetary policy instrument available to central banks when their policy interest rates hit the effective lower bound. QE in its most basic form involves the purchase of government bonds in exchange for central bank reserves with the intention to retain them for a significant length of time. In an era in which central banks pay interest on reserves, QE is an exchange of one interest-bearing liability of the state for another. Under the textbook expectations hypothesis of the yield curve, QE can have no effect on bond yields if there is no change in the expected path of the policy interest rate and therefore no effect on output, employment or wages. In these circumstances, QE would just be an irrelevant shortening of the average maturity of net public debt.

There is, however, strong evidence that QE programmes have moved bond prices and yields, although the scale and duration of such effects is still debated. The academic literature has focused on two departures from the textbook model to explain why QE reduced bond yields. One theory is that central bank money and government bonds are not perfect substitutes perhaps because markets are segmented due to investors' ‘preferred habitat’ or investors do not like holding the interest rate risk associated with long-term bonds. As a result, a fall in the volume of long-term bonds in private hands can raise the price and lower the yield relative to short-term rates. The alternative explanation is that QE is a means by which central banks can give credibility to forward guidance commitments on policy interest rates. Since central banks will make losses on their bonds if yields rise in proportion to the size of their bond portfolio and unwinding a large balance sheet will take some time, QE backs up the signal that the short-term interest rate will remain low for longer than a time-consistent policy rule would suggest. Lowering the expected path of short-term rates drags down long-term rates through the expectations hypothesis of the term structure.

The laboratory experiments in this paper are designed to see if QE still works even if bonds and reserves are essentially identical and there is no role for monetary policy. The subjects participating in the experiment are put in the situation of large commercial banks that hold a portfolio of bonds and central bank reserves. In a benchmark case, they trade bonds for reserves in a call market over 11 rounds without any involvement by the central bank. Two variants of QE are considered: one in which the central bank buys specified amounts on known dates and holds the purchases to the end of the experiment; and a second in which the central bank buys and then sells all of its accumulated portfolio on known dates.

Under fully rational expectations, neither of these QE operations should change the price. Although it might be thought that prices will rise because the central bank will buy in the future and therefore that prices should rise in advance, each trader has an incentive to try to price just under the existing marginal trader to sell all their bonds at any price above the fundamentals. If each trader follows the same strategy, any price above the fundamental price will be undercut until it disappears.

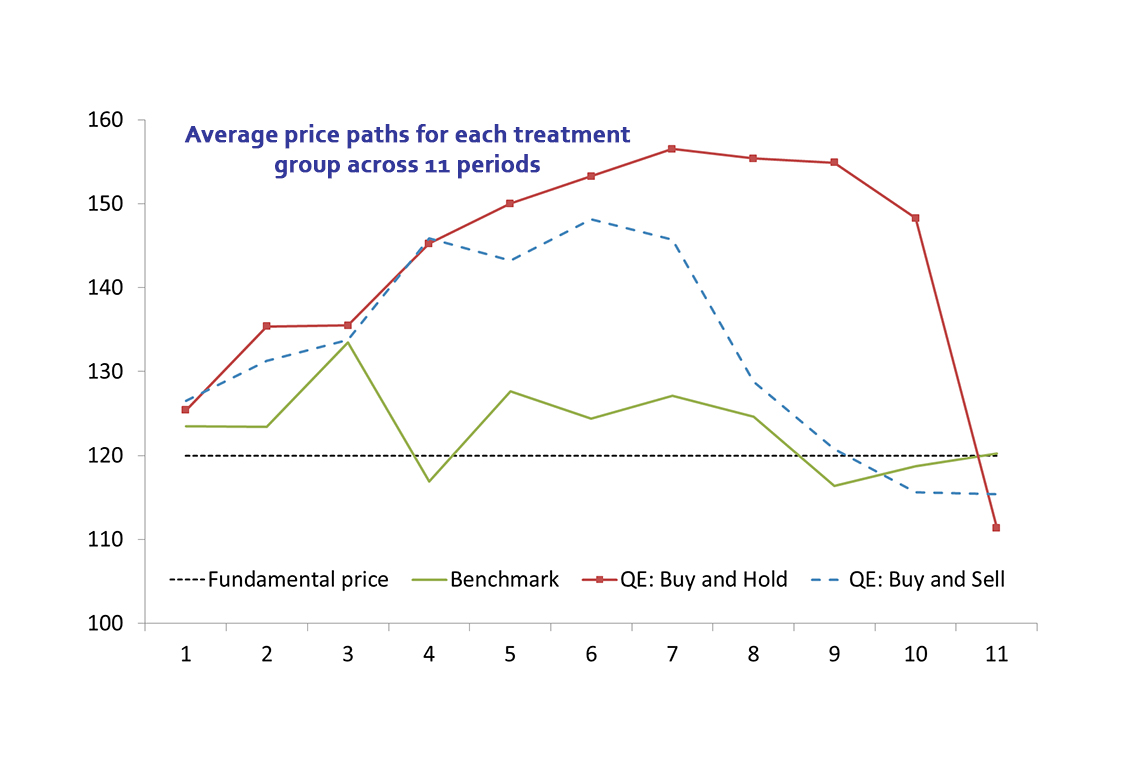

Figure 1 shows that on average the market price in the benchmark case was very close to the fundamental value. However, prices rose well above the fundamental value under QE with buy and hold, only converging on the fundamental price by period 11. By contrast, when the central bank bought and then sold, prices rose above fundamentals but then fall below as the central bank sold. Since the only difference between these experiments is the nature of the central bank's actions, we ascribe the different price paths observed to differences in beliefs about the impact of the central bank's operations.

These differences in beliefs are tracked throughout the experiment. In each period, subjects were asked to provide forecasts of the prices from that period onwards and were given a bonus on top of their trading performance for the accuracy of their predictions. This allows us to observe how the forecasts and outcomes interact and how they are influenced by the central bank. Subject's prior beliefs about the path of prices are significantly higher when they know there will be QE than in the benchmark case. Under the buy and hold scenario, prices track above median initial expectations, causing an upward revision in price forecasts which in turn sustains higher market prices. Price forecasts respond by less in the buy and sell scenarios, consistent with subjects anticipating that prices will be forced down when the central bank sells.

Overall, these experiments suggest that shifts in beliefs could be part of the explanation for the effect of QE on bond prices (although it doesn't exclude the other channels either). Accepting this possibility does not affect any aspects of the transmission mechanism from bond yields to economic activity and ultimately inflation. Where it does matter is whether QE has effects after net purchases have stopped. According to either of the prevailing theories, it is the stock of purchases that matters so a buy and hold strategy sustains a constant accommodative stance. The policy is sustainable fundamentally. In these experiments, prices only remain high after purchases have stopped because of the persistence in beliefs about prices, a phenomenon that in real markets could be revised or overturned by alternative shocks. The accommodative stance after purchases have stopped is thus sustained only by co-ordination of beliefs, which is a less stable equilibrium.

Download the PDF version of this document

- Published on 11/23/2017

- 36 pages

- EN

- PDF (2.61 MB)

Updated on: 06/12/2018 14:11