Working Paper Series no. 791: Semi-Structural VAR and Unobserved Components Models to Estimate Finance-Neutral Output Gap

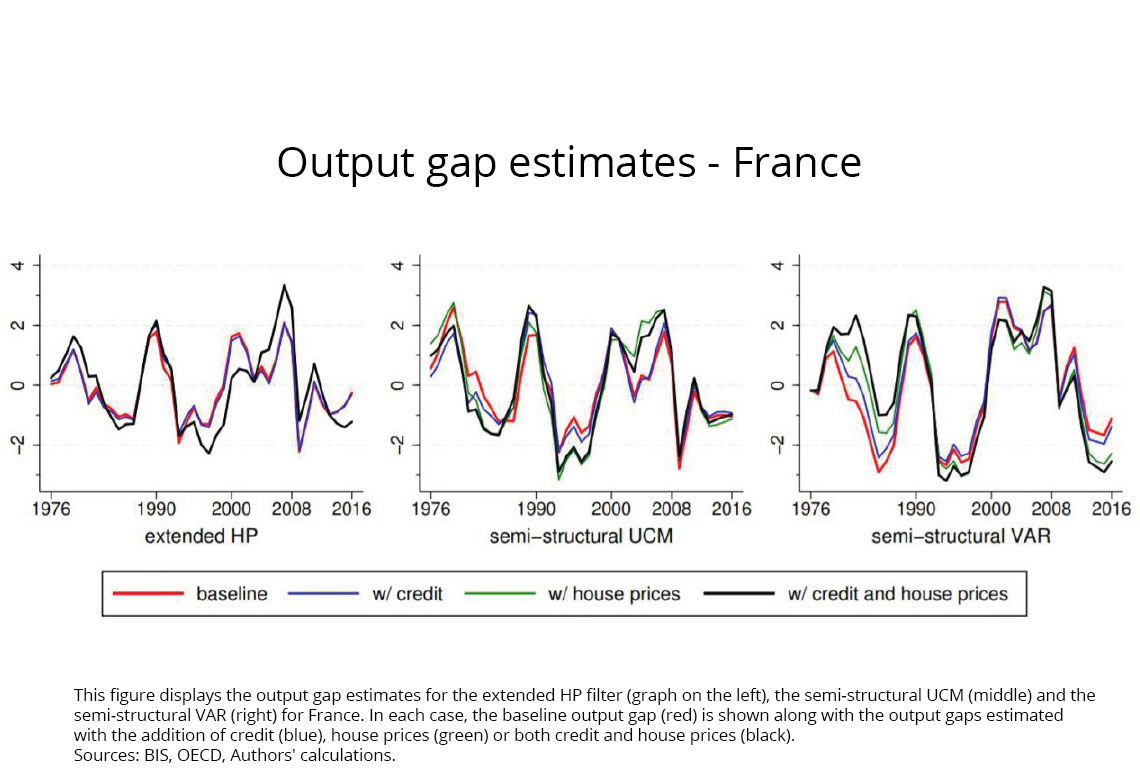

The paper assesses the impact of adding information on financial cycles on the output gap estimates for eight advanced economies using two unobserved components models: a reduced form extended Hodrick-Prescott filter, and a standard semi-structural unobserved components model. To complement these models, a semi-structural vector autoregression model is proposed in which only supply shocks are identified. The accuracy of the output gap estimates is assessed based on their performance in predicting recessions. The models with financial variables generally produce more accurate output gap estimates at the expense of increased real-time volatility. While the extended Hodrick-Prescott filter is particularly appealing for its real-time stability, it lags behind the two semi-structural models in terms of forecasting performance. The vector autoregression model augmented with financial variables features the best in-sample forecasting performance, and it has similar real-time prediction capabilities to the semi-structural unobserved components model. Overall, financial cycles appear to be relevant in Japan, Spain, the UK, and – to a lesser extent – in the US and in France, while they are relatively muted in Canada, Germany, and Italy.

Potential output has been traditionally defined as the maximum level of economic activity attainable without triggering inflation and, in the same context, as the output linked to the level of employment that results in a non accelerating rate of inflation (Okun (1962)). The observed empirical regularity between output fluctuation and the cyclical pattern of inflation or unemployment has been for a long time the key ingredients in a large variety of models aiming to estimate the potential growth and the output gap. However, historical evidence suggests that unsustainable developments in the financial and housing sectors can generate large imbalances in the economy even if inflation and unemployment are low and stable (see e.g. White (2006); Hume and Sentance (2009); Schularick and Taylor (2012); Jordà et al. (2013)).

The paper assesses the impact of adding information on financial cycles on the output gap estimates for eight advanced economies using two unobserved components models: a reduced form extended Hodrick-Prescott filter, and a standard semi-structural unobserved components model. To complement these models, a semi-structural vector autoregression model is proposed in which only supply shocks are identified. The model is a modified version of Blanchard and Quah (1989) in which we exploit a wider set of information by using several (business and financial) cycle indicators without imposing further restrictions. The main idea is that since the potential growth builds upon supply shocks only, one set of constraints, stating that only supply shocks have permanent effects on the level of GDP in the long-run, is enough to recover the trend. We formally show that further restrictions are not needed as the different demand shocks are not interpreted and do not need to be separately identified.

The overall picture underlines the importance of taking financial variables into account when assessing the cyclical position of the economy. Independently of the model considered, the model augmented with financial variables proves to be consistently more effective in identifying unsustainable economic growth paths and in predicting recessions both in-sample and out-of-sample. In Spain, the United Kingdom and (to a much lesser extent) the United States, the credit and house prices boom in the run-up to the Great Recession is clearly identified, as well as a previous boom-bust in the United Kingdom during the 1980s-90s.

In Japan both credit and house prices booms at the turn of the 1990s led to the well-studied and prolonged crisis (the “Lost Decade”). In France the models signal a house prices boom during the 2000s, but there is no sign of a credit boom during the estimation period. Finally, the financial cycles appear relatively muted in Canada, Germany and Italy.

Download the PDF version of this document

- Published on 12/18/2020

- 54 pages

- EN

- PDF (895.54 KB)

Updated on: 12/18/2020 16:11