Working Paper Series no. 692: When Short-Time Work Works

Short-time work programs were revived by the Great Recession. To understand their operating mechanisms, Pierre Cahuc, Francis Kramarz & Sandra Nevoux first provide a model showing that short-time work may save jobs in firms hit by strong negative revenue shocks, but not in less severely-hit firms, where hours worked are reduced, without saving jobs. The cost of saving jobs is low because short-time work targets those at risk of being destroyed. Using extremely detailed data on the administration of the program covering the universe of French establishments, they devise a causal identification strategy based on the geography of the program that demonstrates that short-time work saved jobs in firms faced with large drops in their revenues during the Great Recession, in particular when highly levered, but only in these firms. The measured cost per saved job is shown to be very low relative to that of other employment policies.

Also called short-time compensation, short-time work is a public program targeted at firms facing temporary negative shocks. The design aims at reducing job destruction through work-sharing, by subsidizing firms to lower hours of work while providing earnings support to employees facing these reduced hours. Short-time work can avoid inefficient job destruction induced by firms facing limited access to credit due to capital market imperfection. Short-time work has existed in many countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) for many years and has experienced a renewal of interest from a policy perspective following the 2008-2009 Great Recession. However, despite short-time work increasing in popularity, even in recent academic work, very little is known about the causal impact of this scheme on employment.

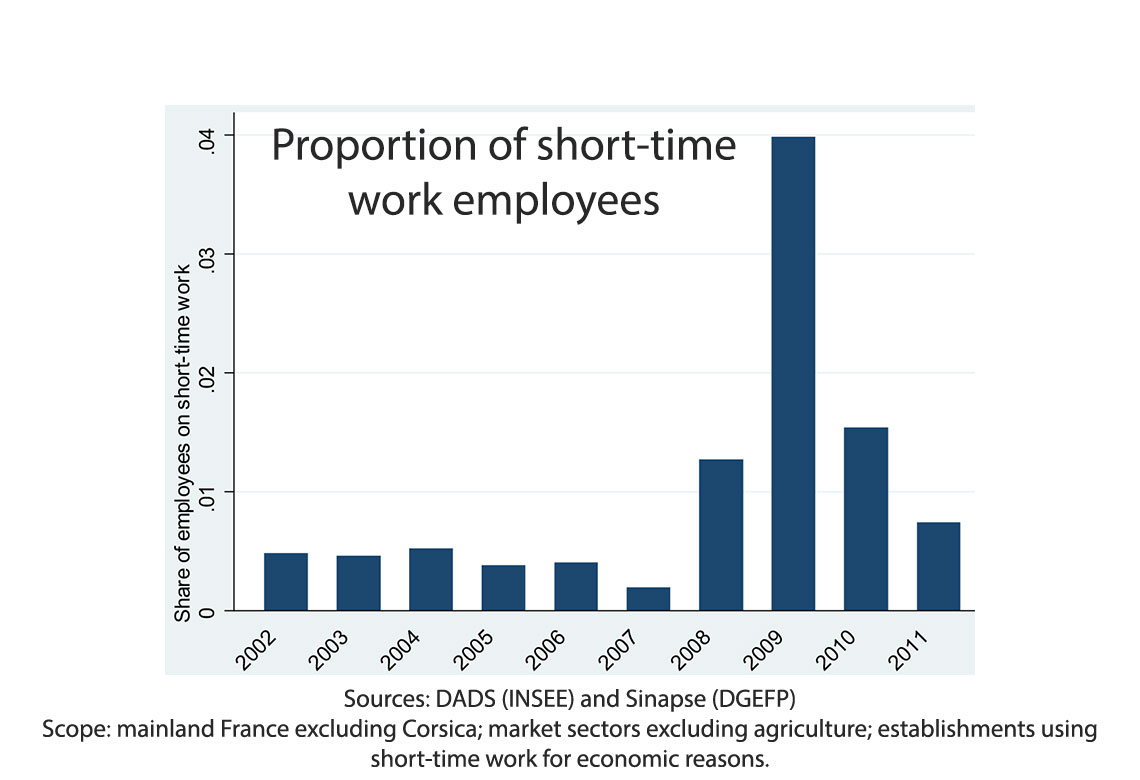

Our recent paper helps to fill this gap by taking advantage of the massive expansion of the French short-time work program during the Great Recession. From the end of 2008, the Ministry of Labor not only expanded the policy budget, but also wrote circulars and directives, in order to promote the use of short-time work as rapidly as possible. As a result, the share of employees on short-time work increased from 0.3%, in 2007 just before the Great Recession, to 4% in 2009, the year of program expansion. Subsidies per non-worked hour and subsidies per employee were respectively multiplied by 1.4 and by 2.5 between these two dates. The cost of the policy trebled, multiplied by a factor of 20. By precisely analyzing the program, both in its principles and in its practical implementation, we show the extent to which, and explain why, short-time work works – both from a theoretical and an empirical perspective.

On the theoretical side, we demonstrate how short-time work saves jobs when firms face a sharp drop in their revenues. We also show that firms facing a limited decrease in revenues are likely to use short-time work to reduce hours for jobs at no risk of being destroyed. In fact, short-time work is shown to be particularly helpful for credit-constrained firms which use the program to partly finance the jobs they need to hoard during a very negative shock. Despite the potential windfall effects just mentioned for mildly-hit or credit-unconstrained firms, the cost per saved job is shown to be small compared with other employment policies. In contrast to wage subsidies paid independently of hours worked, short-time work gives firms the right incentives to use subsidies for jobs at risk of being destroyed rather than other jobs, insofar as they pay a fraction of the remuneration of non-worked hours. To put it differently, because firms will select those jobs at risk of being destroyed for inclusion within short-time work programs, low-productivity jobs that may need financial support to survive during recessions are targeted much more precisely than what most other policies such as wage subsidies can do. Hence, short-time work can help in sustaining employment in recessions at a small cost.

On the empirical side, we use administrative data providing remarkably detailed information about short-time work use, employment, and financial characteristics for all French establishments at annual frequency over the period 2007-2011. To deal with the selection of firms into short-time work, we document the role of the local administration in charge of managing the policy at the local (département) level. The local administration duties comprise informing firms about the policy, the management of applications, and the payment of short-time work subsidies to firms. Their autonomy in management creates strong behavioral heterogeneity, in particular in their response time to applications, across the 95 départements of mainland France before the Great Recession. This administrative response time is shown to play a key role in the implementation of short-time work. We also document how the policy diffuses from one firm to another at the local level. Geographical proximity of short-time work users before the recession is shown to favor the use of short-time work in 2009, controlling for the response time of the administration. In particular, short-time work use diffuses in 2009 from those multi-establishment firms which used short-time work in 2008 because they were located in a département with a short response time. Hence, firm-to-firm diffusion, even though unknown in its exact details, appears to have a key role. This diffusion may stem from firm-to-firm information transmission. It may also arise from a not going alone effect, which reduces the negative signal (for potential financial difficulties) associated with using short-time work vis à vis the firm’s employees, the firm’s trading partners, or the firm’s creditors. Because a) the response time of the département before 2009 has an impact on short-time work use in 2009 of single-establishment and multi-establishment firms and b) short-time work use diffuses from multi-establishment firms to the other firms, we construct the following instruments for the use of short-time work in 2009 for firms which did not use short-time work in the two years preceding 2009 a) the 2008 response time to short-time work applications in the firm’s département and b) the (physical) distance of the firm to the closest multi-establishment firm which used short-time work in 2008. Hence, we claim that the results that are summarized now are causal.

First and foremost, short-time work has a clear positive impact on employment and survival of firms facing the largest potential drop in their revenue, in particular when these firms are highly levered. By contrast, short-time work has no effect on employment and survival of the other firms. As a result, about half of the short-time work users in 2009 benefit from windfall effects since they received short-time work subsidies for jobs at no risk of being destroyed. Nevertheless, short-time work saved jobs overall and also limited the drop in the total number of hours worked. For every worker on short-time work, 0.2 jobs are saved and the total volume of hours increases by 10% of her usual number of hours worked. Fully in line with our model’s predictions, despite the windfall effects mentioned above, the cost per saved job (i.e. the total amount of subsidy needed to save a job) by short-time work in 2009 is estimated to be equal to 7% of the average labor cost, hence very low when compared with other such employment policies. Because the government saves about 25% of the average labor cost when a low-wage individual moves from non-employment to employment, short-time work caused a reduction of public expenditures in 2009. Moreover, we do not find that short-time work mainly saved jobs in structurally weak firms unable to recover after the recession. On the contrary, short-time work allowed highly levered firms, likely to face credit constraints in times of collapsing financial markets, to engage in labor hoarding and recover rapidly in the aftermath of the Recession.

Download the PDF version of this document

- Published on 09/10/2018

- 67 pages

- EN

- PDF (698.99 KB)

Updated on: 10/10/2018 15:11