Working Paper Series no. 786: The 100% Reserve Reform: Calamity or Opportunity?

This paper considers the various 100% Reserve plans that have appeared since the interwar period and have since then been adapted. In all formulations of those schemes, Government liabilities (cash, central bank reserves and short-term Treasuries) back banks’ sight deposits. This organization contrasts with current so-called “fractional reserve banking”, in which, as a result of reserve requirements imposed by the central bank (Drumetz et al., 2015), reserves back only a small fraction of sight deposits. The paper briefly presents the six categories of plans. It then highlights their common features as well as their differences, showing that the differences are more numerous than the common features. The criticisms voiced against the different formulations of 100% Reserves are exposed, adding those of the author and distinguishing between the doubts expressed on the validity of the analysis on one hand, and some undesirable consequences of the reform on the other. In spite of these criticisms, it then shown that the 100% Reserve reform is becoming topical, with recent private sector, central banks and political initiatives that relate to it. Overall, the 100% Reserve reform does not appear as a meaningful opportunity to improve the functioning of banking systems. Furthermore, at least one of its variants could easily turn into a calamity. Fortunately, it is not that variant that is getting more topical.

100% Reserve – also called Full-Reserve – plans have appeared in the interwar period and have since then been adapted, in response either to critiques or to changing circumstances. In all formulations of those schemes, Government liabilities (cash, central bank reserves and short-term Treasuries) back banks’ sight deposits or at least some of them. This is in contrast with current “fractional reserve banking” in which reserves back only a small fraction of sight deposits.

Among the various plans, one can distinguish six main streams. The Chicago Plan (CP) appeared first, in the wake of the Great Depression. Tobin’s proposal for a Deposited Currency (DC) followed much later, in the context of the U.S. savings banks’ debacle. Narrow Banking (NB) was first contemporaneous of Tobin’s proposal but was subsequently adapted on the back of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Limited Purpose Banking (LPB) was developed in the first ten years of this century, in an environment of financial innovation and rapidly expanding financial markets. The most recent proposals, the plan put forward by Benes and Kumhof (2012) (B&K) and Sovereign Money (SM) are based on the premise that the GFC resulted from an allocation of credit to “unproductive” uses.

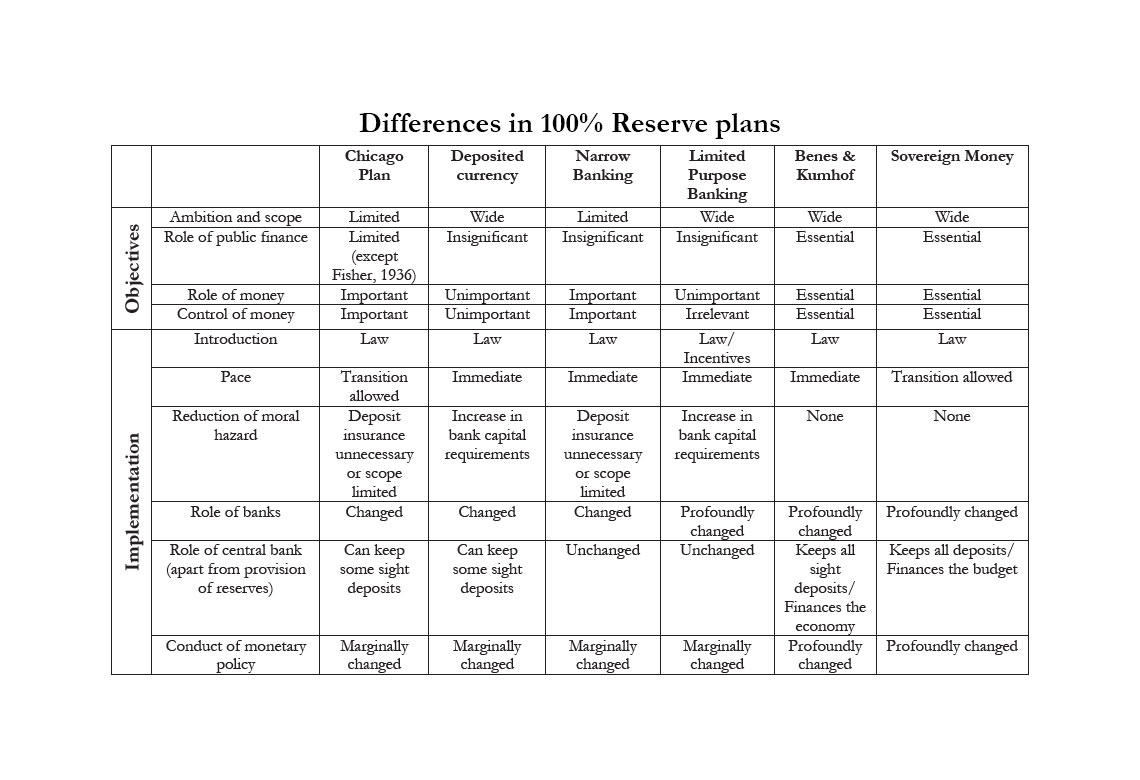

The common motivations of 100% Reserve plans are twofold: make narrow money more controllable (except for LPB); and reduce moral hazard related to the government’s implicit support of banks (especially for LPB). However, there are many differences in the various plans, as shown in the table below.

Overall, several features make B&K and SM distinct from other plans: the wide ambition and broad scope of the reform, the role of public finance considerations in motivating the reform and the one of the Government in implementing it, the tight control on the creation of money and the allocation of credit. In comparison, LPB appears as a “radicalization” of the CP and NB. Finally, DC is original to the extent that it is “à la carte”.

100% Reserve has been criticized by academics from the beginning, including in its own camp. Technical limits relate to the substitutability between sight deposits and other assets, to transition issues, to the difficulty to control money, and in SM to the need to have a correct model of the economy. Criticisms that are more fundamental consider 100% Reserve as too narrow an approach, static, and supporting excessive claims. In particular, LPB over-emphasizes the capacities of financial markets and fund managers, whereas SM has recourse to a notion of “debt-free payment” that has been denounced as an “illusion”. Furthermore, the implementation of some 100% Reserve plans would have consequences that cast doubts on the merits of the whole project. Notably, in SM, monetary policy would risk becoming a compartment of fiscal and industrial policies, and moral hazard would not be eliminated by B&K or SM, as the Government (in B&K) or the central bank (in SM) would play a major role in allocating credit and would thus be held directly responsible for ensuring financial stability.

In spite of the criticisms it has raised, 100% Reserve could get more topical in the coming years because of private sector, central bank, and political initiatives. In particular, the issuance of global stablecoins by the private sector or of central bank digital currencies by central banks could lead to a loss of resources by banks, as would be the case with 100% Reserve. Fortunately, these projects are reminiscent of DC, the one among 100% Reserve plans least susceptible of upsetting banking intermediation.

Download the PDF version of this document

- Published on 12/02/2020

- 19 pages

- EN

- PDF (860.95 KB)

Updated on: 12/02/2020 17:17