Working Paper Series no. 614: Disaster Risk and Preference Shifts in a New Keynesian Model

In RBC models, “disaster risk shocks” reproduce countercyclical risk premia but generate an increase in consumption along the recession and asset price fall, through their effects on agents’ preferences (Gourio, 2012). This paper offers a solution to this puzzle by developing a New Keynesian model with such a small but time-varying probability of “disaster”. We show that price stickiness, combined with an elasticity of intertemporal substitution smaller than unity, restores procyclical consumption and wages, while preserving countercyclical risk premia, in response to disaster risk shocks. The mechanism then provides a rationale for discount factor first- and second-moment (“uncertainty”) shocks.

During the 2007-2009 financial crisis, risk premia increased significantly in advanced economies. However, generating countercyclical risk premia along with expected macroeconomic variations in response to shocks is particularly challenging. In real business cycle (RBC) models, “disaster risk shocks” can reproduce countercyclical risk premia but generate an increase in consumption during the recession.

Marlène Isoré and Urszula Szczerbowicz offer a solution to this puzzle by developing a New Keynesian model with a very small but time-varying probability of “disaster”. They show that price stickiness, combined with an elasticity of intertemporal substitution smaller than unity, restores procyclical consumption while preserving countercyclical risk premia, in response to disaster risk shocks.

Disaster risk generates risk premia in RBC models but increases consumption …

A central feature of Marlène Isoré and Urszula Szczerbowicz’s model relies on the likelihood of rare disasters hitting the economy. Rare disasters are large adverse events associated with low probability, such as great recessions, wars, terrorist attacks or natural catastrophes. Gourio (2012) introduced a small, time-varying probability of disaster, defined as an event that destroys a large share of the existing capital stock and productivity, into RBC models. An interesting implication is that an increase in the probability of disaster, without the disaster itself occurring, is enough to trigger a recession and an increase in risk premia.

However, this literature faces two limitations. First, an increase in disaster risk generates a recession and a drop in stock prices but it also increases consumption, which seems counterfactual. Second, the model generates drops in output and investment only under the assumption that agents are highly adaptable and are able to substitute consumption between periods in response to shocks. In other terms, the elasticity of intertemporal substitution (EIS) parameter needs to be strictly greater than one. If the EIS is lower than one, the results are completely reversed: in particular, a rise in the probability of disaster would generate a boom in output and investment. Empirical evidence on the EIS confirms that values below unity are realistic and are conventionally adopted in macroeconomic calibrations. Therefore, such a contrasting response from output at the unity threshold to changes in disaster risk seems particularly puzzling.

Disaster risk in NK models restores procyclical consumption and preserves countercyclicality of risk premia

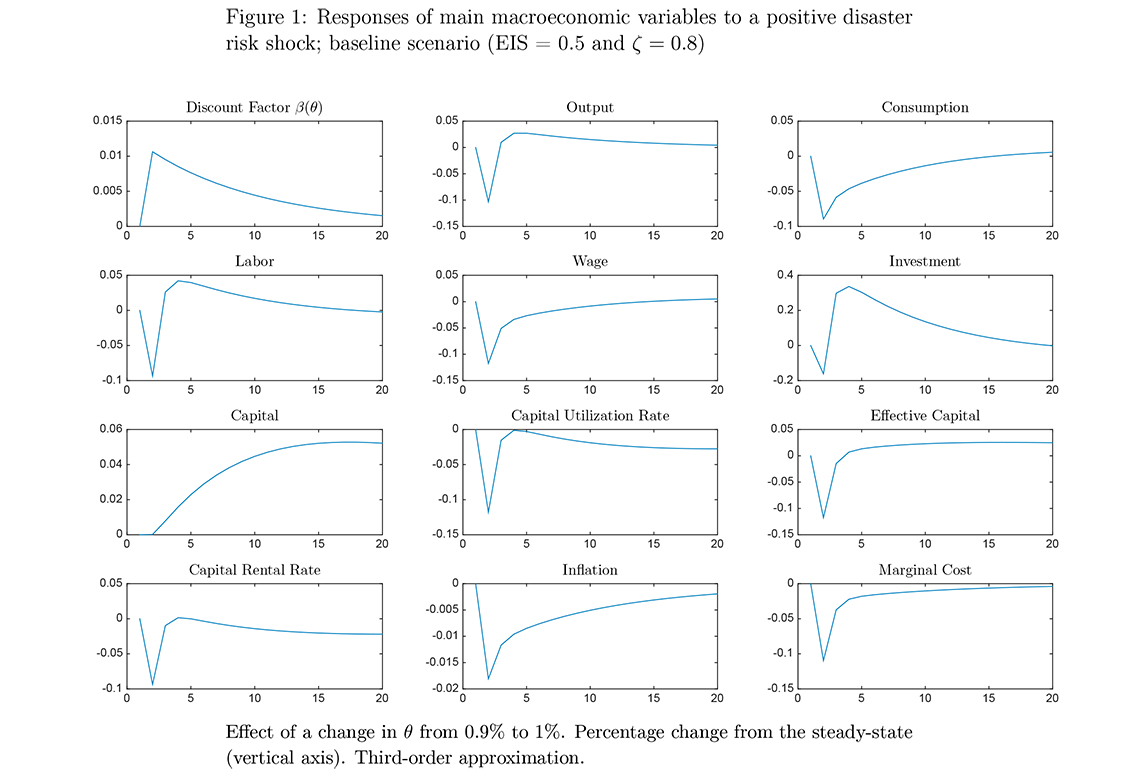

Marlène Isoré and Urszula Szczerbowicz provide a solution to this puzzle by introducing a time-varying probability of disaster à la Gourio (2012) into an otherwise standard New Keynesian model. The main result of their paper consists in demonstrating that price stickiness, combined with an EIS below unity, is able to restore procyclicality of the main macroeconomic quantities. In particular, they show that agents become more “patient” in response to disaster risk shocks: their propensity to save increases and their consumption declines, leading to deflation. Yet, higher savings do not immediately translate into higher investment, and therefore output also drops. As a result, an increase in disaster risk leads to a simultaneous fall in investment, consumption, prices, and output as capital becomes riskier. As for asset prices, the risk premia increase and a ‘flight-to-quality’ effect is visible through the drop in the risk-free rate when the disaster risk shock hits. Hence, while improving predictions for the macroeconomic variables, the model preserves the countercyclicality of the risk premia.

The intuition is as follows. When the EIS is below unity, an increase in disaster risk diminishes agents’ propensity to consume and therefore savings go up. Because of price stickiness, firms cannot deflate the prices of their goods as much as they would like in order to face up to reduced consumption, and thus, they demand fewer factors of production (capital and labour). Therefore, despite the precautionary motives, all macroeconomic quantities are driven down with output. Since the return on capital is riskier following an increased probability of disaster, the risk premia are countercyclical. In other words, introducing a time-varying disaster risk into a full-fledged New Keynesian model is critical, not just to enrich the macroeconomic setting and spectrum of potential policy analysis, but also because for a given value of the EIS, it conditions most of the qualitative effects associated with a change in disaster risk.

Disaster risk provides a rationale for preference and uncertainty shocks

The effects of disaster risk on preferences are embedded into agents’ discount factor both in models by Gourio (2012) and Isoré and Szczerbowicz (2017). However, this discount factor goes up in the latter, as agents are more patient when the EIS is below unity, but goes down in the former. Combined with price stickiness, the responses of aggregate macroeconomic and financial variables to a disaster risk shock in turn resemble the responses to preference shocks and second-moment “uncertainty” shocks. In that sense, Isoré and Szczerbowicz show that disaster risk can be conciliated with first and second-moment discount factor shocks from the New Keynesian literature, recently found to drive the economy into the zero lower bound and secular stagnation. They therefore provide a model which could be used for further investigation of monetary policy responses to changes in the probability of disaster events.

Isoré (M.),Szczerbowicz (U.) (2017), “Disaster risk and preference shifts in a New Keynesian model”, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 79, pages 97-125, June 2017

Download the PDF version of this document

- Published on 12/22/2016

- EN

- PDF (838.16 KB)

Updated on: 01/23/2018 13:06