Working Paper Series no. 676: Firm Dynamics and Growth Measurement in France

Statistical agencies typically impute inflation for disappearing products based on surviving products, which may result in overstated inflation and understated growth. Philippe Aghion, Antonin Bergeaud, Timo Boppart & Simon Bunel use the theory and methodology developed by Aghion et al. (2017) to quantify in the case of France how much of productivity growth is missed by statistical offices because of this. Using the census of plants in France, they find that from 2004 to 2015, about 0.5 percentage point of real output growth per year is not taken into account, which is about the same as what was found in the U.S. While this result suggests that missing growth from creative destruction could structurally be the same in different countries, the authors show that they in fact hide different underlying establishment and firm's lifecycle dynamics in the two countries.

Whereas it is straightforward to compute inflation for an unchanging set of goods and services, it is much harder to separate inflation from quality improvements and variety expansion amidst a changing set of items. Back in 1996, the Boskin Commission increased awareness of potential biases in how the US Bureau of Labor Statistics accounts for new products in calculating the Consumer Price Index (CPI). In particular, the Commission challenged whether the Bureau of Labor Statistics accurately deals with products experiencing model changes by the same producer (e.g. successive years of a car model) and with completely new product varieties. In a recent contribution, Aghion et al. (2017) developed a methodology that deals with new product varieties but also, more importantly, with products that are subject to creative destruction. They highlight and quantify this additional overlooked source of bias that has to do with imputation to around 0.6 percentage point per year.

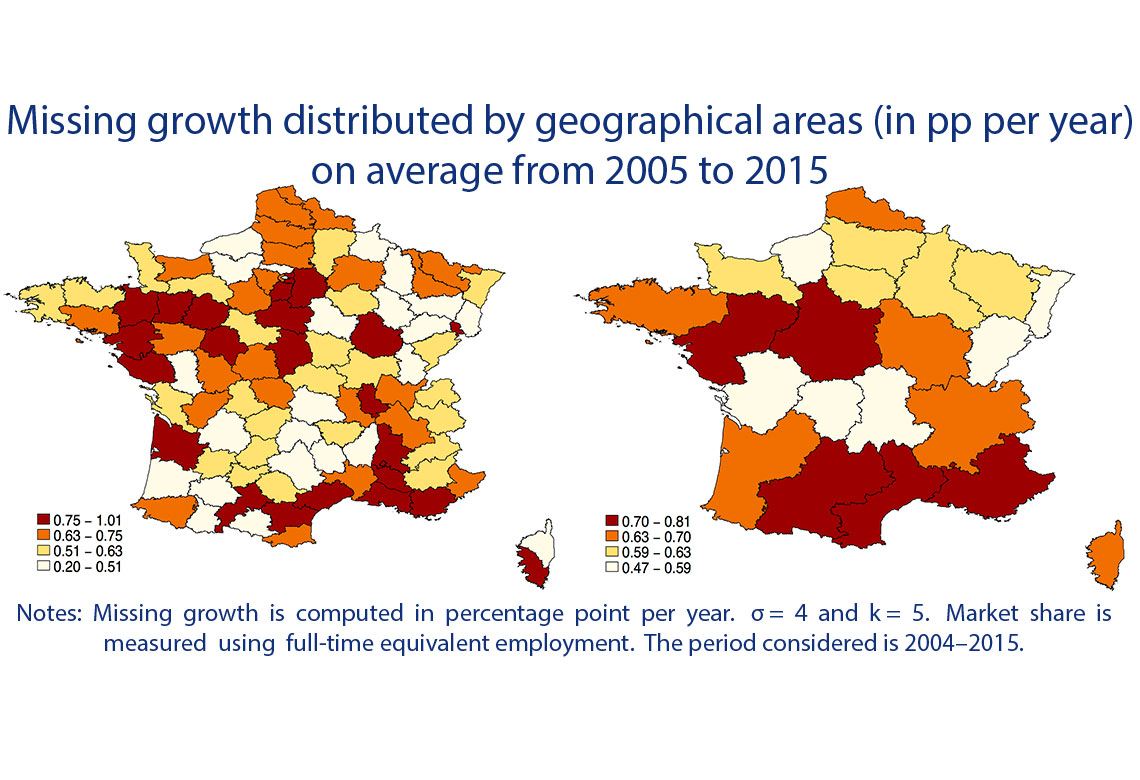

In this paper, we consider the case of France and apply the same methodology to data covering the universe of plants in this country. We find that on average, growth is underestimated by about 0.5 percentage point. We then look at how this missing growth is distributed among sectors and geographical areas. One interesting finding that can be seen in Figure 1, is that missing growth is not evenly distributed geographically, and that the areas where the measurement bias is larger, are already the areas in which measured growth is higher. This suggests that territorial inequalities are perhaps larger than thought.

More generally, the areas where mismeasurement of growth is more important are those where the rates of creative destruction of establishments and employment are the largest.

Does the fact that we find similar number than in the US for missing growth suggests that somehow structurally, imputing the price of missing items results in underestimating growth by about 0.5 percentage points? The answer seems to be more complicated as we see in a second part of the paper. Firm and plant dynamics are very different in France than in the US, and in particular employment share of small firms is larger in France, but the market share of exiting establishment is also larger in France. These two features cancel out so that the market share of incumbent grows at a similar pace in the US and in France.

Download the PDF version of this document

- Published on 04/13/2018

- 35 pages

- EN

- PDF (1018 KB)

Updated on: 04/13/2018 09:46