Working Paper Series no. 742: Fiscal and Monetary Regimes: A Strategic Approach

This paper develops a full-fledged strategic analysis of Wallace's “game of chicken”. A public sector facing legacy nominal liabilities is comprised of fiscal and monetary authorities that respectively set the primary surplus and the price level in a non-cooperative fashion. We find that the post 2008 feature of indefinitely postponed fiscal consolidation and rapid expansion of the Federal Reserve's balance sheet is consistent with a strategic setting in which neither authority can commit to a policy beyond its current mandate, and the fiscal authority moves before the monetary one at each date.

Policy responses to the 2008 crisis have resulted in a massive increase in the liabilities of many fiscal and monetary authorities. In the face of stretched public finances, the question of the interdependence of fiscal and monetary policies has come back to the foreground of policy discussions.

Monetary economists often use a game-theoretic terminology to describe this interdependence. This can be traced back to Wallace's view of a “game of chicken” played among branches of government that control separate elements of the budget constraint. Yet despite these informal references to game theory, this interaction between fiscal and monetary policies has not to our knowledge lent itself to a thorough strategic analysis. The goal of this paper is to develop a general and agnostic strategic analysis of this interaction.

We model Wallace's “game of chicken” as...a game between a fiscal and a monetary authority that jointly face legacy public liabilities. We posit that each authority controls a policy instrument. The fiscal authority sets the real fiscal surplus and the monetary one sets the price level at each date. Both authorities can also trade nominal intertemporal claims---government debt and remunerated reserves, respectively---with the private sector. Each authority incurs costs when its respective policy instrument strays away from a target. Both also incur costs from outright sovereign default.

Our goal is to characterize the equilibria resulting from each set of assumptions on payoffs and strategic interactions, and from there to back out the set of assumptions that delivers the most plausible empirical implications. This way we seek insights into the question that Sargent and Wallace (1981) raise in conclusion of their unpleasant arithmetic: “The question is, Which authority moves first, the monetary authority or the fiscal authority? In other words, Who imposes discipline on whom?”

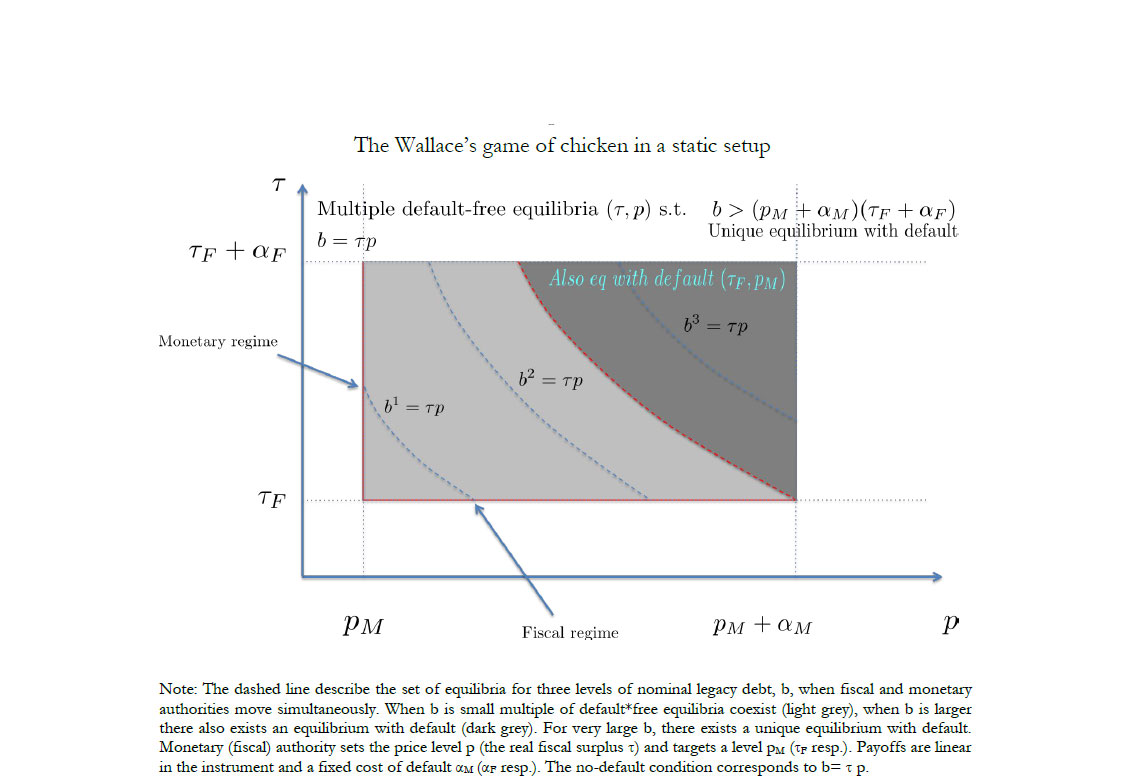

We start with a simple static version of the game that generates two main insights. First, this game is an actual “game of chicken” only when default costs are convex: accommodation by one authority makes playing tough more appealing to the other. The fixed default cost that is commonly assumed in the literature on sovereign default introduces by contrast a coordination motive among authorities: Accommodation by one of them may make accommodation by the other relatively more attractive (see the figure below). As a result, pure-strategy equilibria with and without default coexist in the presence of fixed. Second, we find that simultaneous games have unappealing properties that limit their practical relevance. We conclude that sequential games are more practically relevant theoretical tools. But, selecting the most relevant game among these requires an answer to Sargent and Wallace's question about who moves first.

In order to answer this question, we then study a dynamic game. Our results are twofold. First, the fiscal authority can force the monetary one to depart from its target and inflate debt away even when the monetary authority moves first at each period. To do so, it needs to roll over government debt until the outstanding amount is sufficiently large that the monetary authority cannot impose full fiscal accommodation, as the fiscal authority would prefer to default in this case. Second, in order to commit to inflation levels that are ex-ante desirable but that would be ex-post excessive, the monetary authority expands its balance sheet by creating sufficiently large amounts of reserves in order to purchase publicly held government debt. This is a credible commitment to future inflation as low future price levels would be inconsistent with the central bank's solvency in (the out-of-equilibrium) case of sovereign default.

We overall conclude that the version of the model in which the fiscal authority moves first is best suited to describe US public finances since 2008. First, this version is the only one in which the central bank significantly and immediately expands its balance sheet whereas the government postpones fiscal consolidation to the longer run. Second, this version is the only one in which inflation is also postponed to the long-run. Overall, our strategic analysis thus suggests that the answer to Sargent and Wallace's question is: the fiscal authority moves first.

Download the PDF version of this document

- Published on 11/29/2019

- 59 pages

- EN

- PDF (2.37 MB)

Updated on: 12/02/2019 08:25