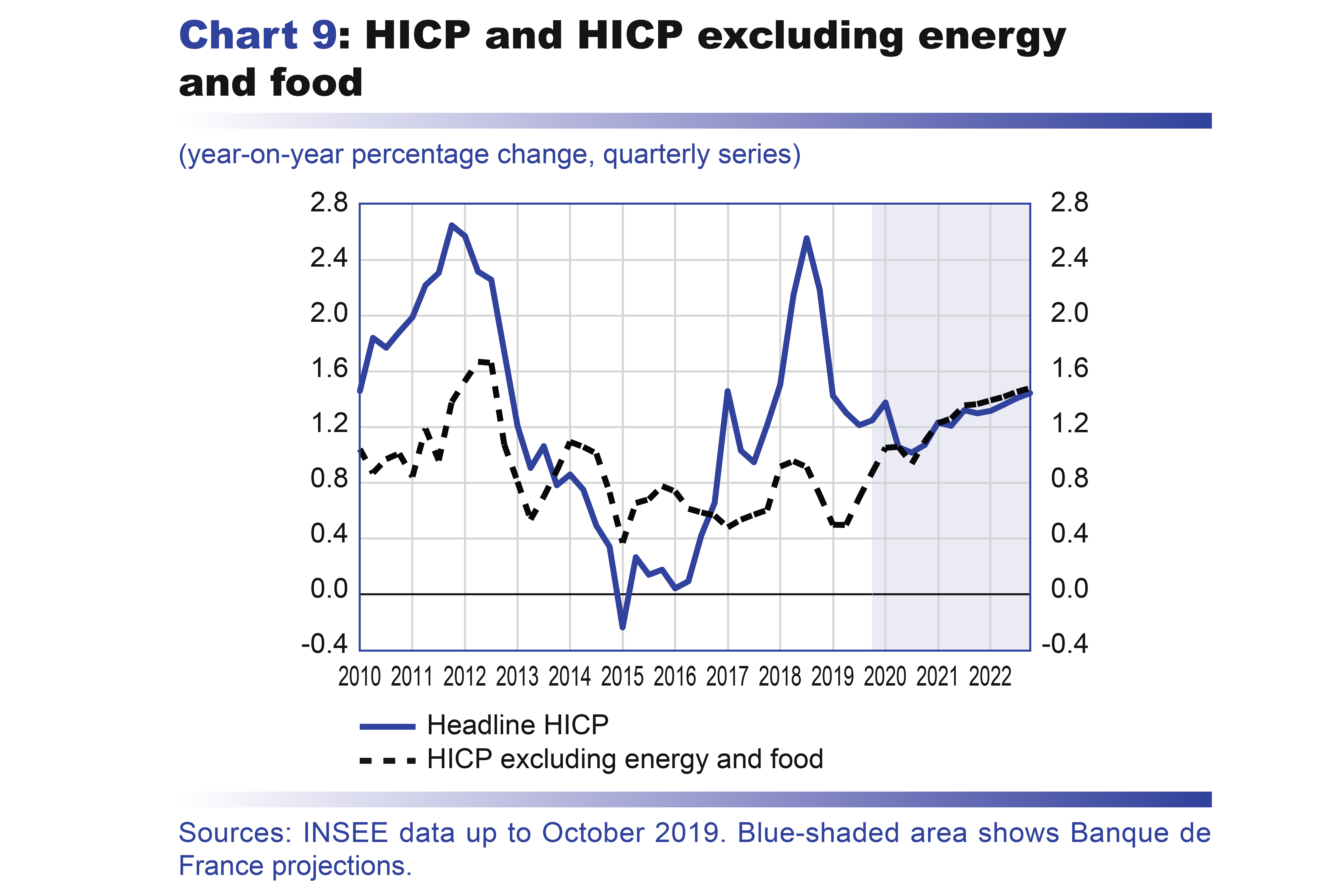

Inflation should fall to a low of 1.1% in 2020 due to a slowdown in energy and food prices, but is then seen recovering gradually to 1.4% in 2022, essentially on the back of higher services prices

HICP inflation has gradually decreased over 2019, and came out at 1.2% in the third quarter of the year (see Chart 9). The decline is mainly the result of a slowdown in energy and food inflation. On the one hand, energy prices have seen weaker growth due to the drop in oil prices and the cancellation of the hike in the domestic consumption tax on energy products (TICPE) at the beginning of 2019, both of which had a strong upward impact on energy prices in 2018. On the other hand, although food prices remain dynamic, they have nonetheless slowed overall throughout the year. The slowdown was particularly marked in September and October 2019, following the sharp price rises over the summer triggered by high temperatures across France.

Inflation excluding energy and food has risen slightly over the year: after a particularly subdued first half with the rate remaining at around 0.5%, it strengthened again in the third quarter to 0.7%. Services inflation has gained traction over the year, rising from less than 1% in the first half to around 1.5% at the end of the third quarter.

In 2019, headline HICP inflation should thus come out at 1.3% in annual average terms, while inflation excluding energy and food is expected to average 0.6%. These figures are unchanged from our September projections.

In 2020, HICP inflation should moderate further to 1.1%, with the decline stemming mainly from energy and food. After lower growth in 2019, energy prices are expected to trend downwards in 2020, in line with the trajectory of oil prices. Meanwhile food inflation should also continue to slow from its summer 2019 peak. In contrast, inflation excluding energy and food is projected to remain on its recent upward trend, reaching 1.0% in 2020. The increase should mainly be driven by services inflation, which is predicted to rise to an annual average rate of 1.8% in 2020.

Following this soft patch, headline HICP inflation should then pick up again to 1.3% in 2021 and 1.4% in 2022, and by the end of the horizon should be supported more evenly by its different components. Food inflation should continue to ease, largely as a result of smaller tobacco price rises than in the recent past. Energy inflation is predicted to gain momentum again gradually, but should nonetheless remain weak. Inflation excluding energy and food is expected to continue to rise, reaching 1.3% in 2021 and 1.4% in 2022. The upward trend should be helped by stronger growth in manufactured goods prices, but is mainly expected to be driven by services inflation, which is seen hovering around 2.0% in annual average terms in 2021 and 2022. This should reflect the dynamism of the labour market and wages.

However, in line with the September projections, inflation excluding energy and food is expected to follow an uneven trajectory owing to various economic policy measures: social housing rents are expected to be cut again in January 2020 (after a first reduction in June 2018); flight prices are projected to rise with the introduction of a new ecotax in January 2020, and prices of optical products, hearing aids and dental prostheses are expected to fall with the gradual introduction of the zero excess law between 2019 and 2021 (although the price of complementary health insurance is anticipated to rise).

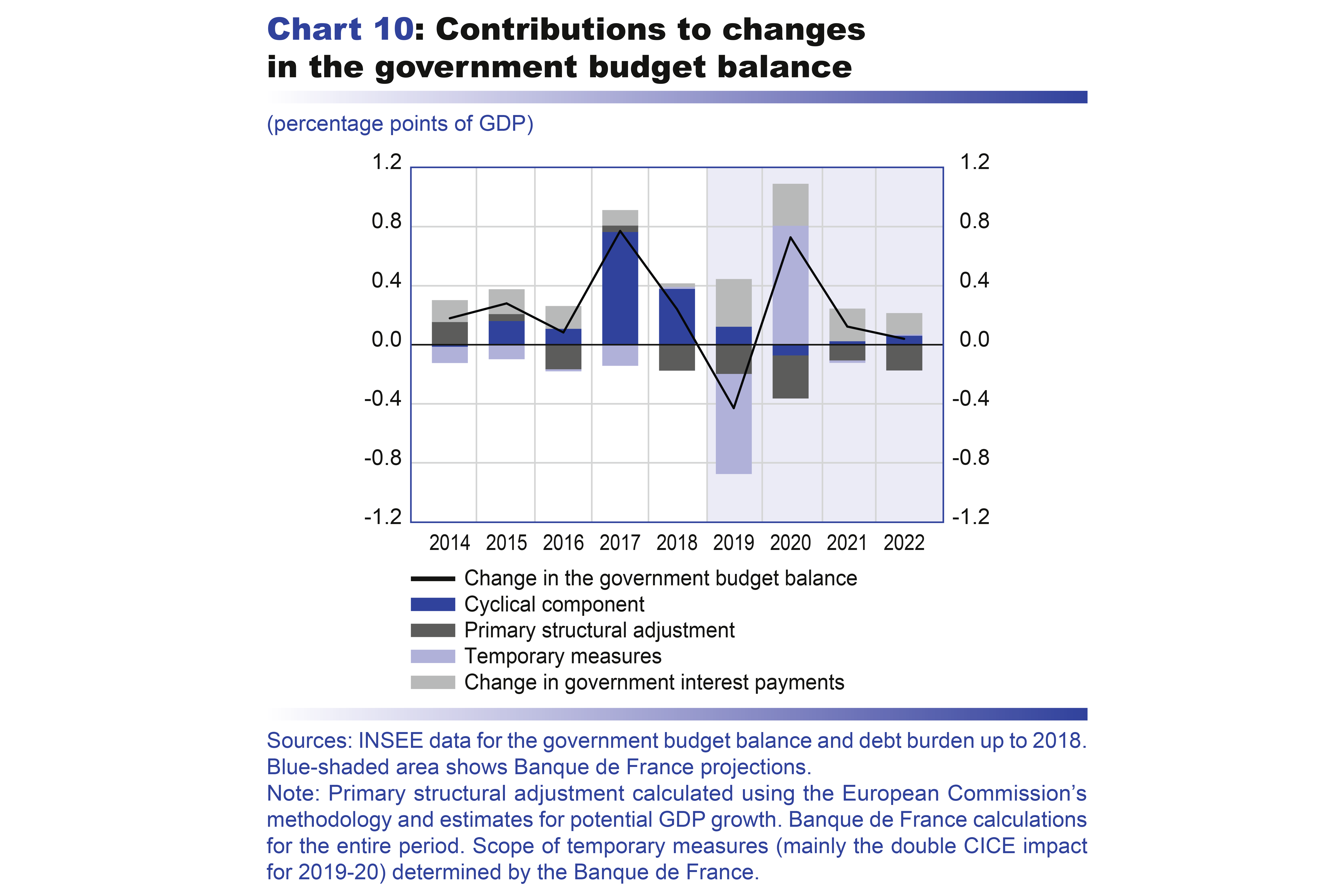

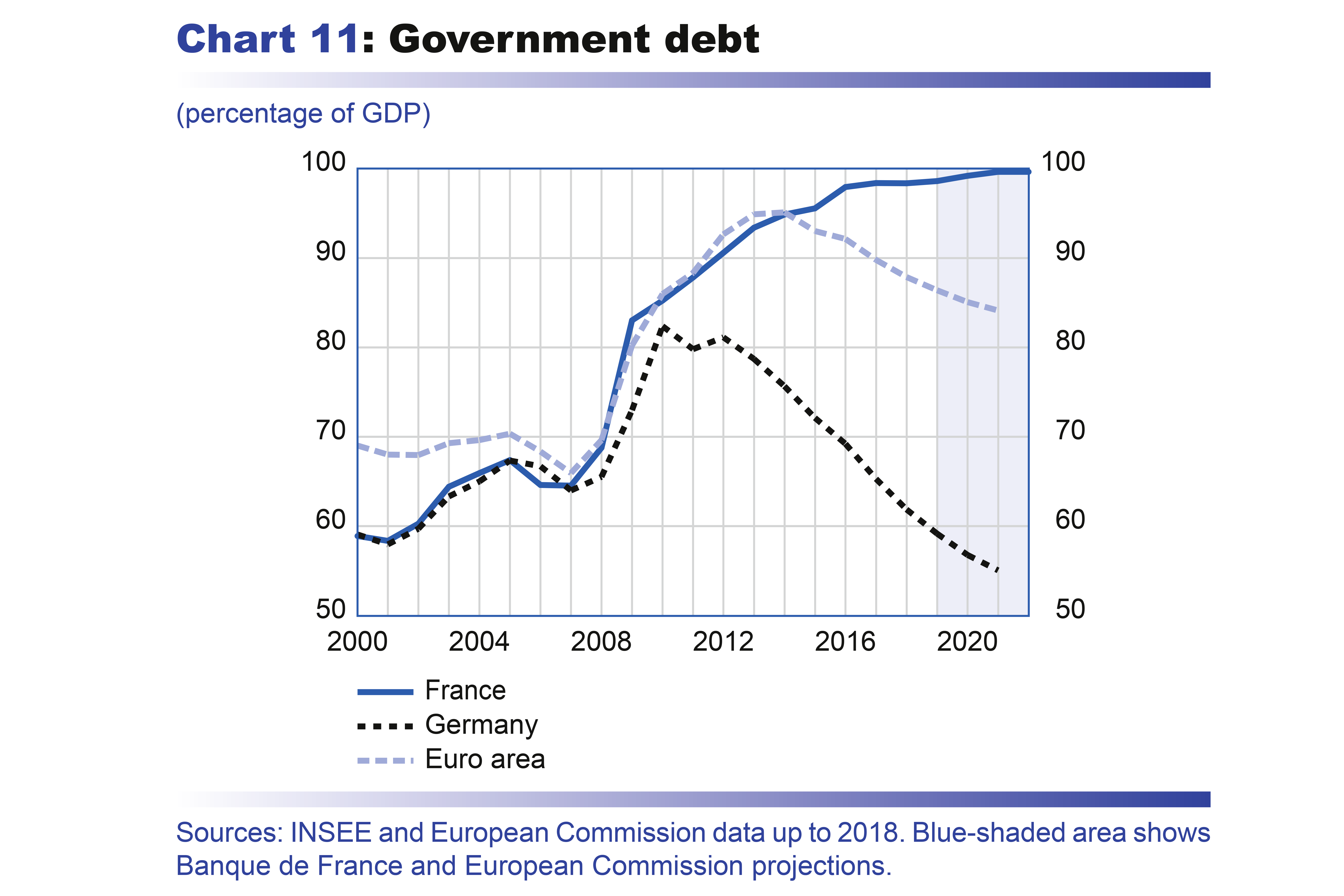

The government deficit should tend towards 2% of GDP and government debt should stabilise at just below 100% of GDP, with significant tax cuts taking effect and spending growth set to remain robust, excluding the decline in interest payments

The government deficit is projected to widen to 3.0% of GDP in 2019 from 2.5% in 2018 owing to the transformation of the CICE into a permanent cut in employer social security contributions. Excluding this temporary impact, however, the deficit is estimated to come out at 2.1% of GDP for 2019. It should then reach 2.2% of GDP in 2020, before narrowing slightly towards a level close to 2%. These projections factor in all information contained in the 2020 budget law, and the recent announcements regarding the emergency plan for hospitals. In 2021 and 2022, only those measures set out in sufficient detail have been taken into account in our projections.

The aggregate tax-to-GDP ratio (taxes and social security contributions as a percentage of GDP) is predicted to fall to 44.1% by 2021-22, after reaching 45.2% in 2018. The cuts to taxes and social security contributions set out in the 2020 budget law (reform of the income tax brackets in 2020, gradual abolition of housing tax on principal residences for the remaining 20% of wealthier households as of 2021) will add to the reductions in the tax burden already included in previous budget laws (abolition of housing tax for 80% of households, full year of cuts to employee sickness and unemployment contributions, exemption of overtime from tax and social security contributions, gradual cut in corporation tax).

Government spending (excluding tax credits) is expected to rise by an average of 1.8% per year in nominal terms over the period 2019-22, and by 0.8% in real terms (adjusted for CPI excluding tobacco), of which 0.1 percentage point will be due to a scope effect with the incorporation of France Compétences into general government. Although certain measures should result in significant slowdowns in spending growth (freezing of the index points in the public sector pay grid, below-inflation rises in social security benefits, unemployment benefit reforms), the biggest savings come from the ongoing fall in interest payments due to historically low interest rates. Primary spending (excluding tax credits and interest payments) should in fact continue to rise by an average of 1.2% per year in real terms over 2019-22, which is close to the trend rate over the last ten years and to potential GDP growth.

The government’s structural deficit, calculated using the European Commission’s methodology and estimates for potential growth, should only narrow marginally over 2019-22, from 2.7% of GDP in 2018 to 2.5% of GDP in 2022, with the improvement stemming solely from lower interest payments. The primary structural adjustment is anticipated to be negative over the projection horizon (cumulative adjustment of -0.8 percentage point over 2019-22). According to these projections, government debt will rise again slightly up to 2021, then stabilise at just below 100% of GDP in 2022. In other words, the savings from the lower interest payments are expected to be matched by a relaxation of fiscal policy. This more active fiscal stance raises the question of its qualitative content:

an assessment of its effects on growth, including over a medium-term horizon, should lead to a prioritisation of investment and spending on the future.