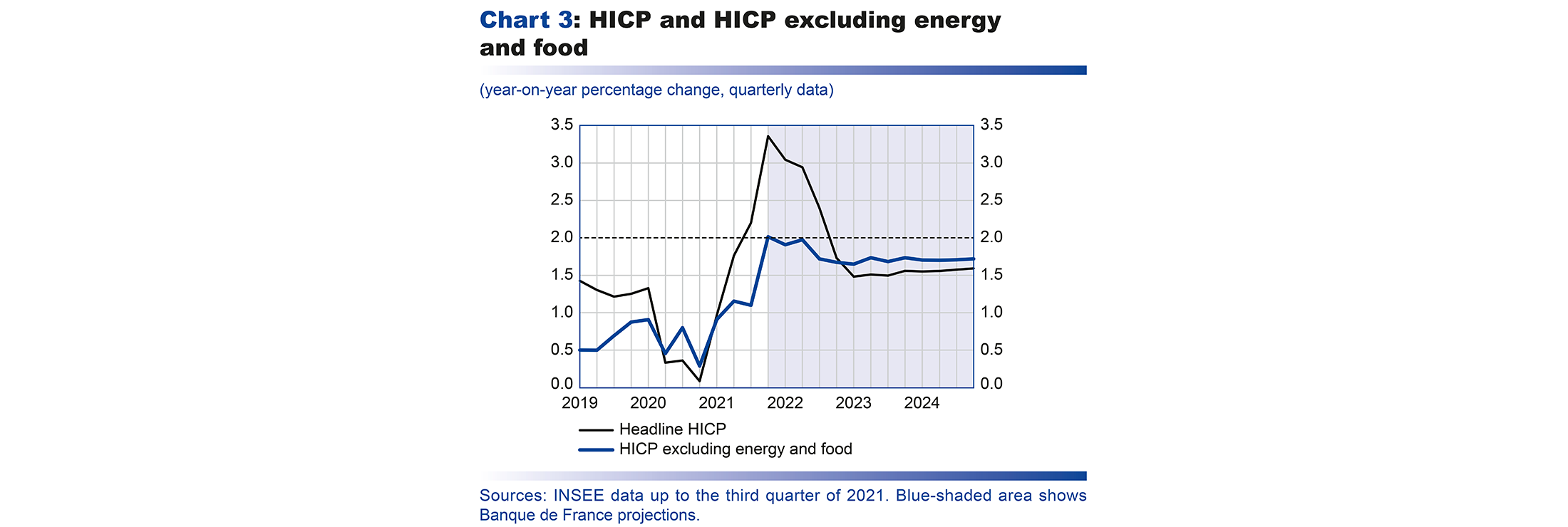

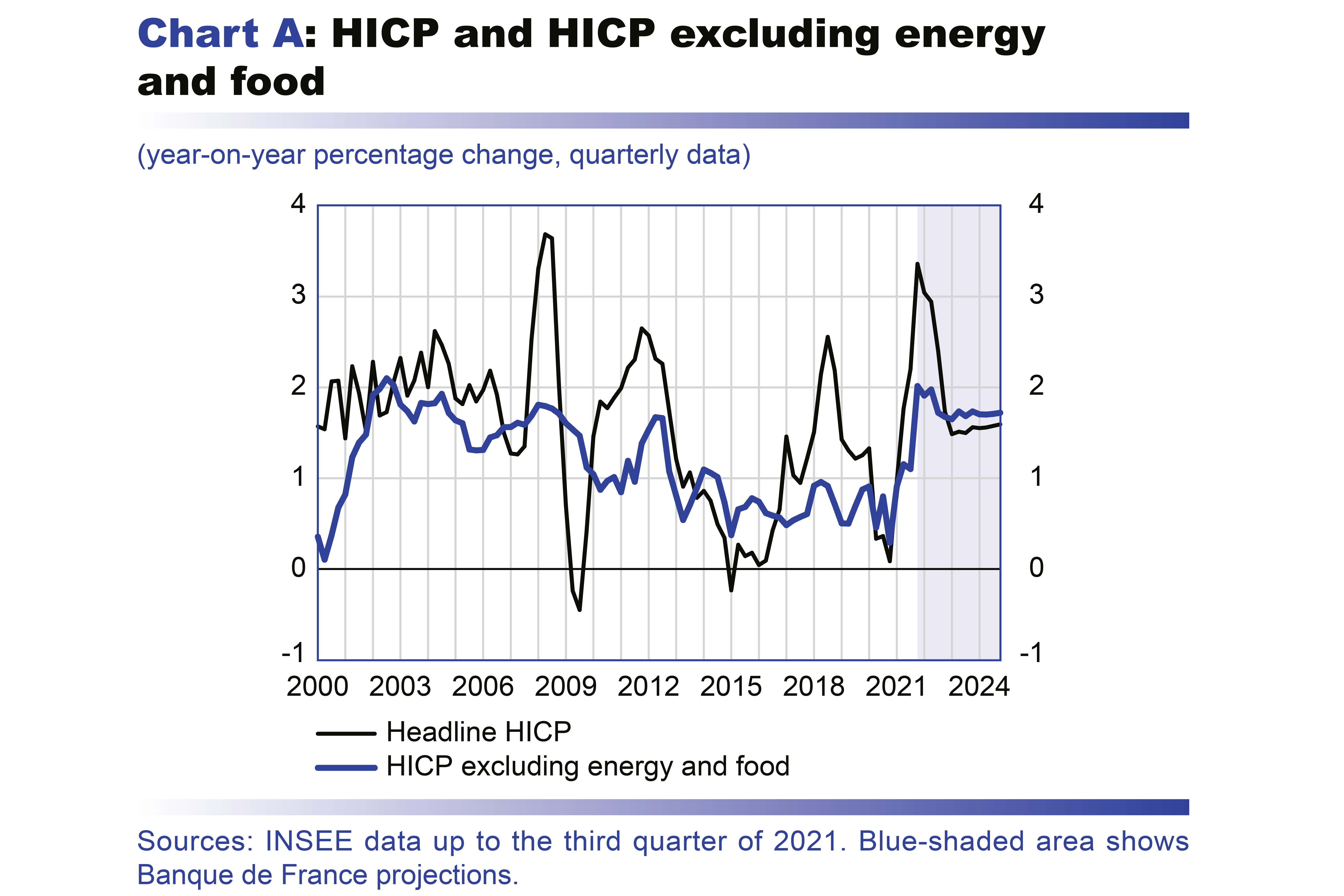

According to our projections, after the 2021-22 “hump” (see Chart A), headline HICP inflation in France is expected to come back down to 1.5% then 1.6% in 2023-24. It should be driven by the component excluding energy and food, which is projected to rise at an annual average rate of 1.7% in both years. This key component is thus expected to post year-on-year increases close to those reached before the 2008 financial crisis (see Chart A). In particular, we use 2002-07 as the benchmark period, since HICP inflation stood at around 2%, and HICP inflation excluding energy and food was fairly stable at around 1.7%.

By comparison, between 2013 and 2020, the average year-on-year increase in the HICP excluding energy and food was very different, at only 0.7%. The services component of the HICP was especially sluggish, with the year-on-year increase averaging 1.2%, well below the average of 2.7% between 2002 and 2007. Conversely, the average year-on-year change in the manufactured goods component was less pronounced and only slightly lower than the 2002-07 average (–0.1% compared with 0.2%).

In 2022, HICP inflation excluding energy and food is already expected to be relatively strong due to the peak – which we believe to be temporary – in the manufactured goods component (annual average rise of 1.3%), caused by global supply pressures, while the services component should no longer be as weak as in previous years. After that, the determinants keeping HICP inflation excluding energy and food at 1.7% in 2023-24 should progressively change and become more significant over the medium-term (see Chart B). This is what we detail below.

After peaking in 2022, the rise in manufactured goods prices is expected to gradually return to its long-term average (see Chart B), close to 0%, as supply difficulties ease. In our baseline scenario, the current tensions should have persistent effects on manufactured goods prices, which should not correct downwards as was the case after the 2012 peak. However, in 2023-24, changes in manufactured goods prices should no longer affect the trend in inflation as significantly as in 2002-07.

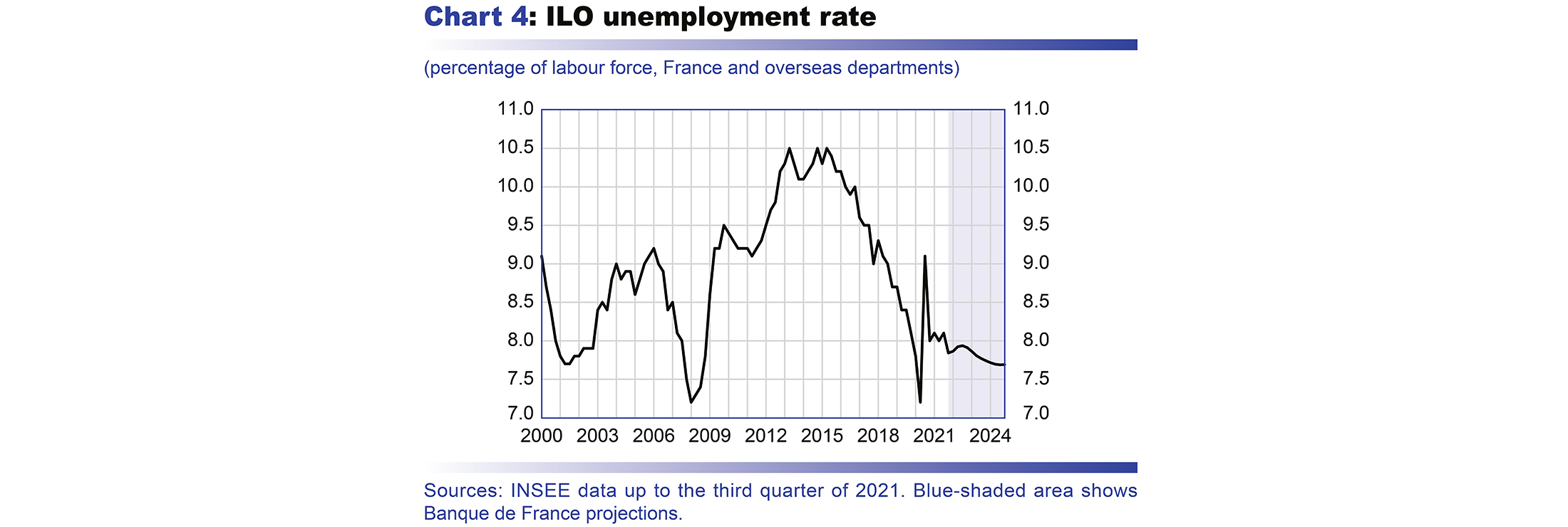

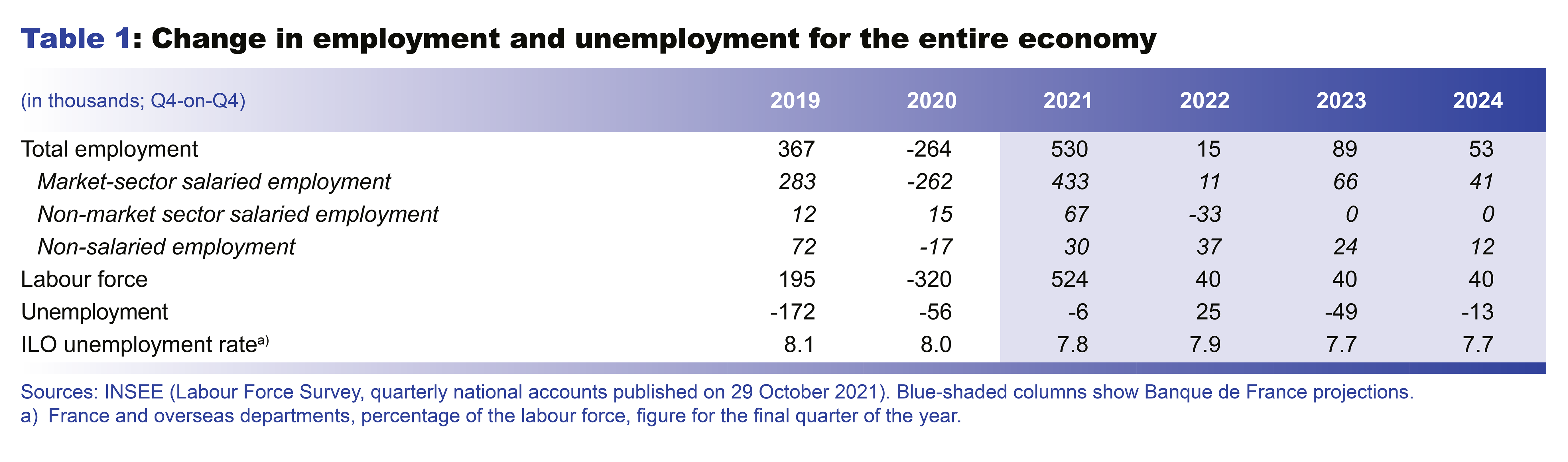

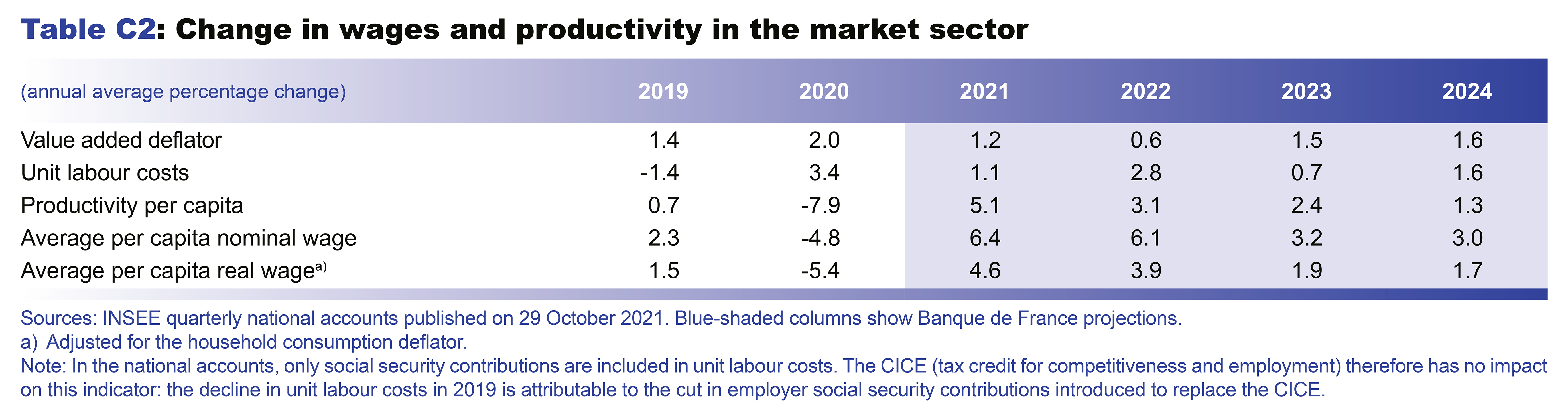

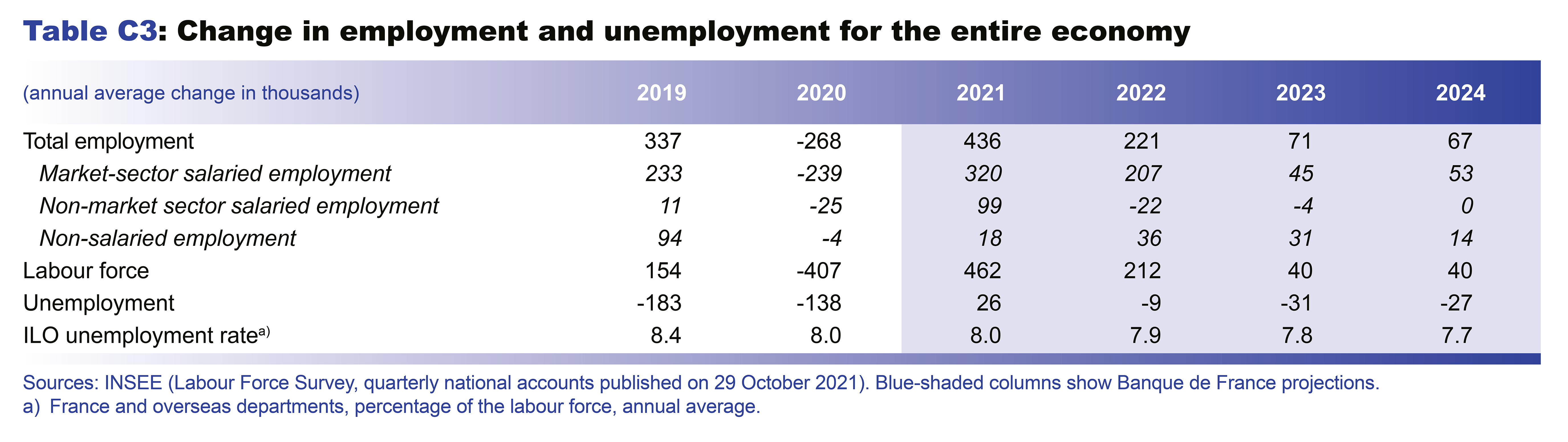

Meanwhile, in 2023-24, price increases in services are expected to continue to be markedly more dynamic and should thus support HICP inflation excluding energy and food, as in 2002-07. The services component of the HICP is expected to rise by 2.5% in 2023, then by 2.7% in 2024. The private services component should even post a 2.9% increase in 2023, i.e. a rate identical to that observed in the 2002-07 period. This increase should be supported by wage growth, driven up by a lastingly low unemployment rate from a historical perspective, and takes account of the recruitment difficulties reported by companies in our short-term business surveys. This scenario also incorporates the usual pass-though of prices to wages and of wages to prices over the entire projection horizon, but assumes that long-term inflation expectations remain anchored given the credibility of monetary policy, thus avoiding an inflationary spiral.

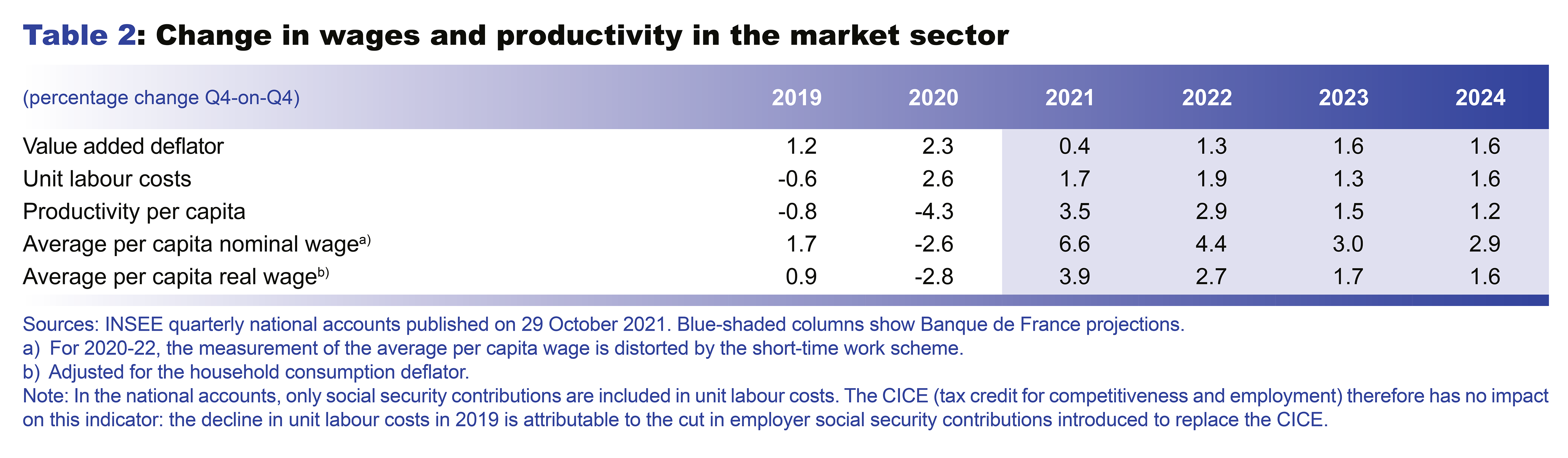

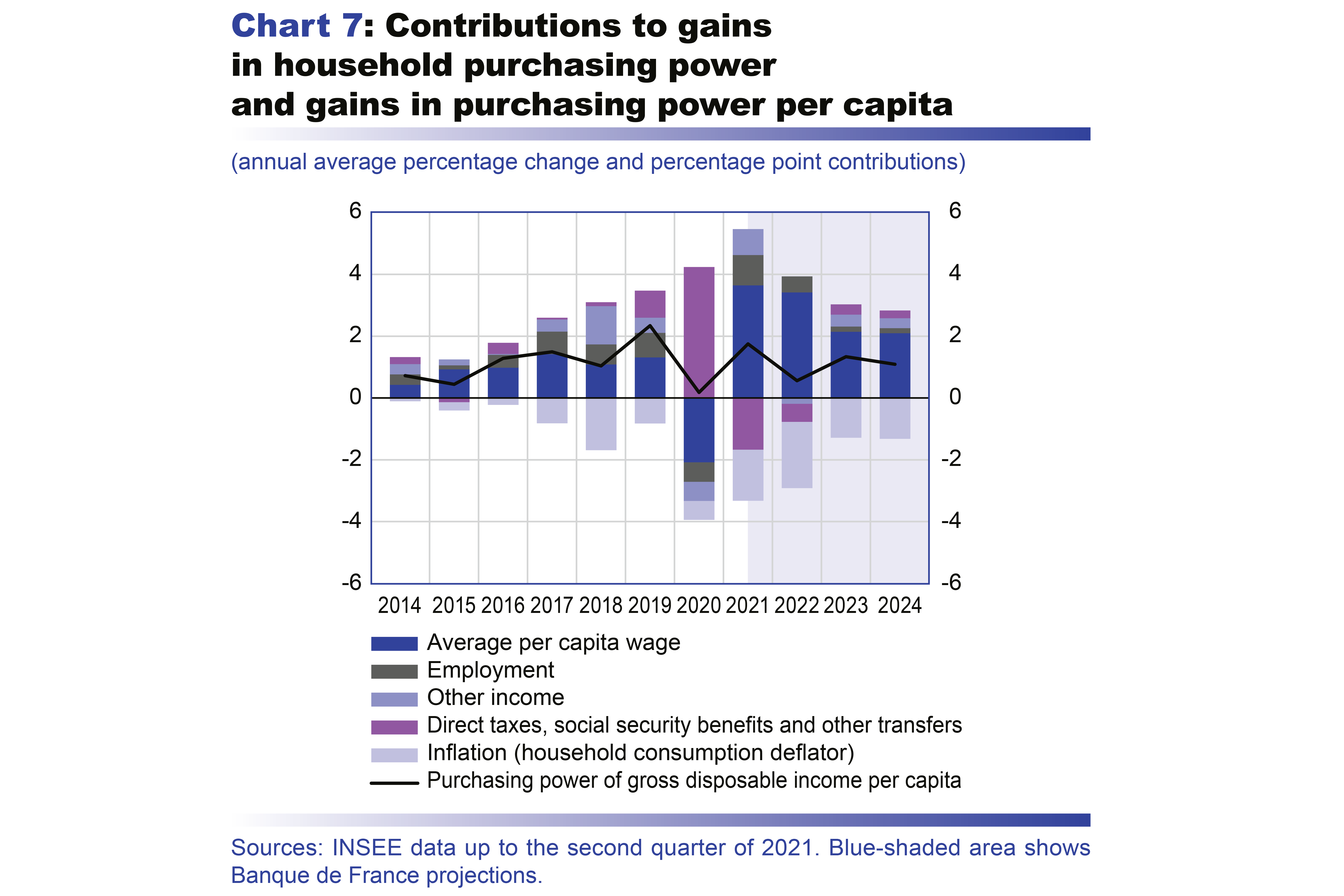

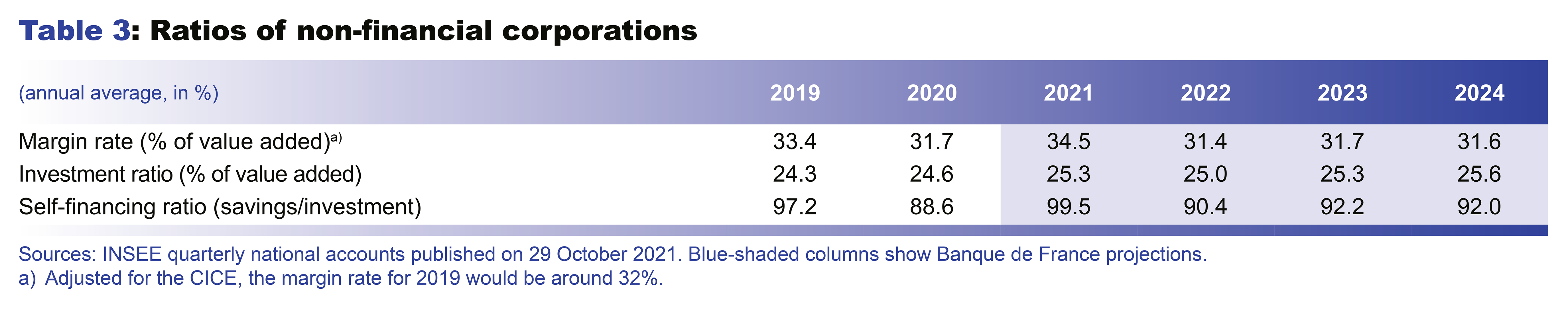

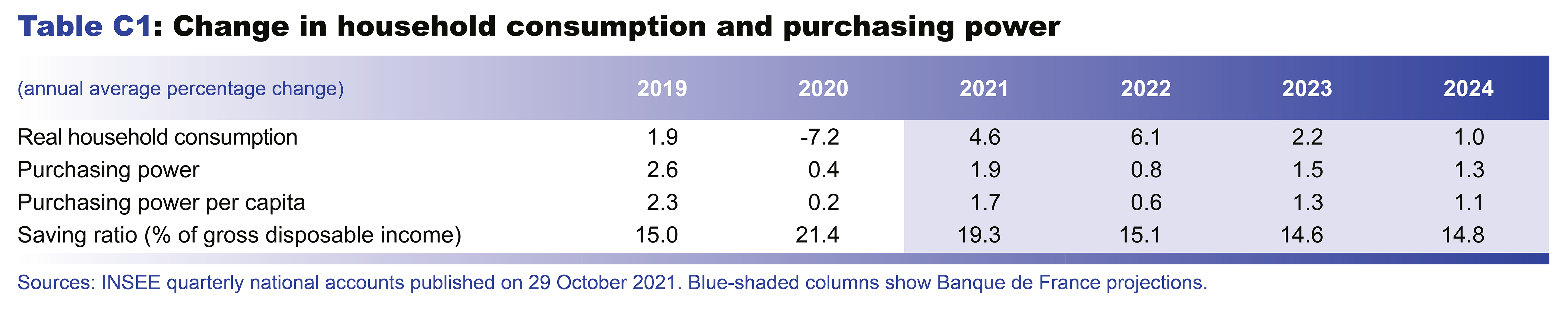

In this scenario, price increases are expected to be passed on partially to wages, and vice versa, in line with the trends observed since the start of the 2000s. We should then see a convergence towards fairly robust household purchasing power growth, at 1.4% on average over the two years, while the corporate margin rate should remain at a level close to that observed prior to the Covid-19 crisis, thanks to wage increases in line with productivity gains.