Like the rest of the world, the French economy suffered a shock of unprecedented proportions in the first half of 2020

From January to March 2020, the Covid-19 epidemic spread across the world at an unexpected speed. Due to the lack of a vaccine and intensifying pressure on healthcare systems, many countries were forced to take drastic measures to slow the advance of the virus. As a result, the shock to world economic activity was brutal, and it plummeted in the first half of 2020. In the euro area, where most countries imposed lockdown measures, GDP dropped by 3.8% in the first quarter and, according to the most recent Eurosystem projections, should fall back by a further 13% in the second quarter.

France introduced a strict lockdown in mid-March. In our business assessments published at the start of April and May, we estimated an immediate reduction in activity of around 32% during the two weeks of lockdown in March, and then of around 27% in April. According to INSEE’s second estimate of the quarterly national accounts, published at end-May, GDP fell by 5.3% in the first quarter of 2020.

The decline in GDP will mechanically intensify in the second quarter, which covers six weeks of lockdown until 11 May followed by a very gradual exit. Therefore, there will be a far greater loss of activity compared with the average recorded in the first quarter, which only included two weeks of lockdown (see Chart 1). In our projections, GDP in the second quarter of 2020 is thus expected to decline by a little over 15% versus the first quarter.

This second-quarter trajectory was finalised on 25 May. It is consistent with the economic information that has since become available, particularly the Banque de France surveys published today, which suggest a loss of activity of 17% at end-May, coming back to a loss of around 12% at-end June. Furthermore, these projections were constructed on the basis of the INSEE quarterly accounts published at the end of April and do not take into account the detailed first-quarter accounts (together with the annual accounts for 2019) which were published on 29 May and in which GDP growth was revised upwards from –5.8% to –5.3%. Given the size of the decline expected in the first half, this revision would only have a marginal effect on our projections.

Assuming reduced but continuing disruptions during the second half of 2020, GDP for the entire year is expected to decline by more than 10%

For the second quarter of 2020, we can still base our estimate of the loss of activity on available information, particularly that from our business surveys. Beyond this horizon, we have to apply assumptions. With regard to the international and financial environment (see Table A in the appendix), our projections are based on those of the Eurosystem, finalised on 18 May and published on 4 June for the entire euro area. After the economic and public health shocks that varied in their timing and scale at the beginning of 2020, the economic constraints associated with the circulation of the virus should become more uniform for the different euro area countries (see Chart 1).

In terms of public health and economic developments, we mainly apply two assumptions.

First, the virus will continue to circulate and therefore hinder the rebound in economic activity. However, we do not factor in any new deterioration that would necessitate reintroducing a strict lockdown.

Second, we assume that the improvement in the public health situation and adaptation of businesses to the new circumstances will mean that losses of activity compared to normal are gradually reduced despite the continued circulation of the virus. The example of certain countries where the initial economic shock was less severe can serve as a point of reference. We thus assume further losses of activity, compared with a no-crisis scenario, of around 10 percentage points in the third quarter and close to 7 percentage points in the fourth quarter of 2020. Under these gradual recovery conditions, GDP should fall by around 10% in 2020.

By way of illustration, and in line with the European Central Bank’s publication of 4 June, Box 1 presents a “severe” scenario, in which the disruptions remain more acute, and also a “mild” scenario, in which a more substantial reduction in the circulation of the virus by the end of 2020 should facilitate a return to a normal level of activity by the end of the year.

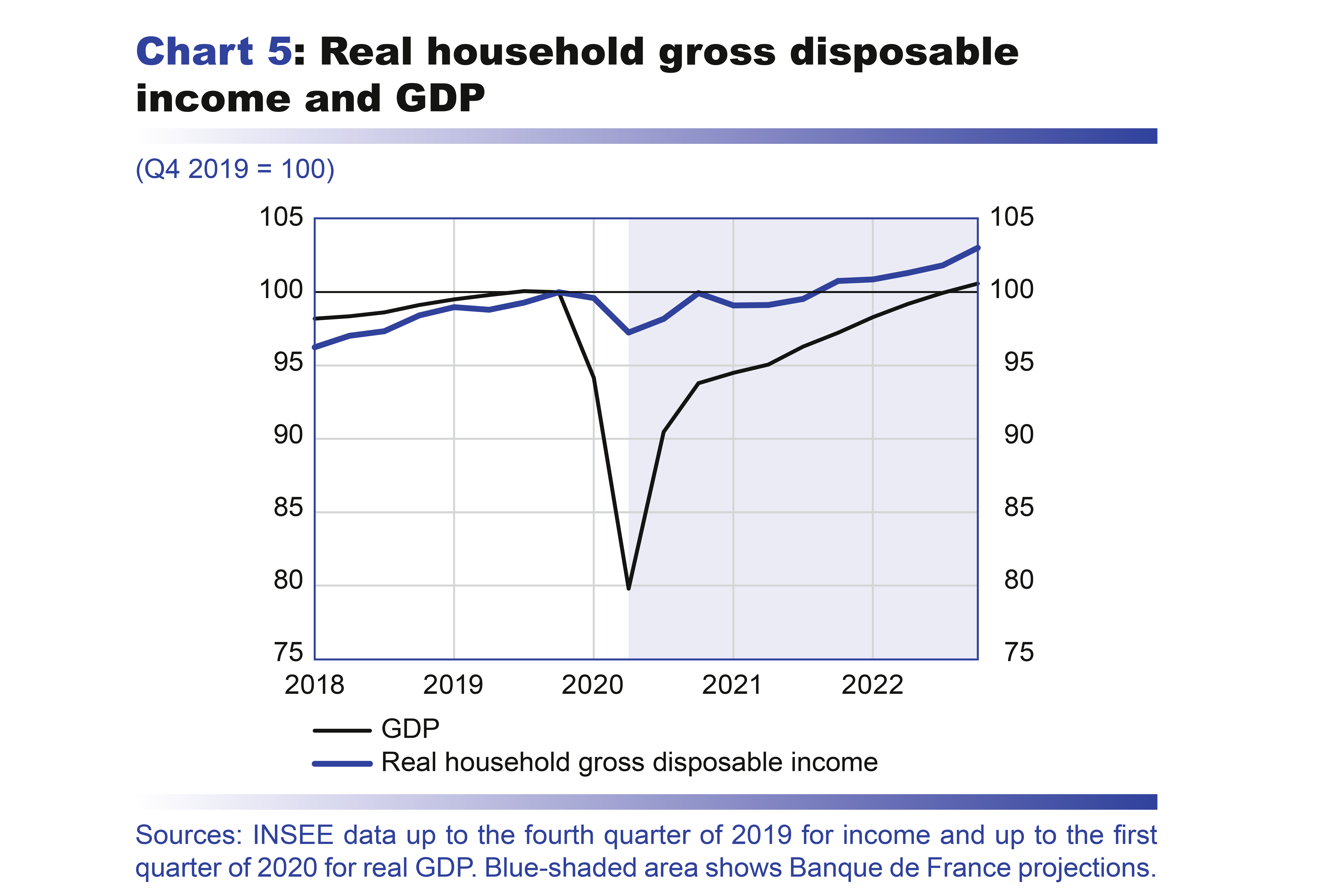

With a gradual pick-up in activity, real GDP should return to its end-2019 level in 2022 according to our baseline scenario

Even greater uncertainty surrounds the forecasts for 2021 and 2022 than for those of the second half of 2020. They are based on the assumption of a gradual exit from the crisis. We anticipate GDP growth of around 7% and 4% in 2021 and 2022 respectively (see Chart 1). Despite this ostensibly sharp upswing, activity is not expected to return to its end-2019 level until mid-2022. Both 2021 and 2022 are thus expected to be years of marked but gradual recovery. Growth should then ease, returning to its potential rate beyond our projection horizon.

In 2021, the very sharp annual average improvement in activity should mainly be linked to the expected upturn in the second half of 2020 after the shock during the first half of the year. The growth carry-over for 2021 is thus already expected to be almost 5% at the end of 2020. The recovery should continue through the beginning of 2021, assuming that the economy continues to adapt to the public health constraints.

Growth in activity is expected to strengthen from the second half of 2021. In keeping with the Eurosystem’s projections for the euro area, we assume that in mid-2021, medical breakthroughs will mean that public health measures can be lifted. Household and business confidence would thus improve and the upturn in activity begun at the end of 2021 would continue into 2022, buoyed by a declining household saving ratio (see below). This would give a further boost to annual growth in 2022.

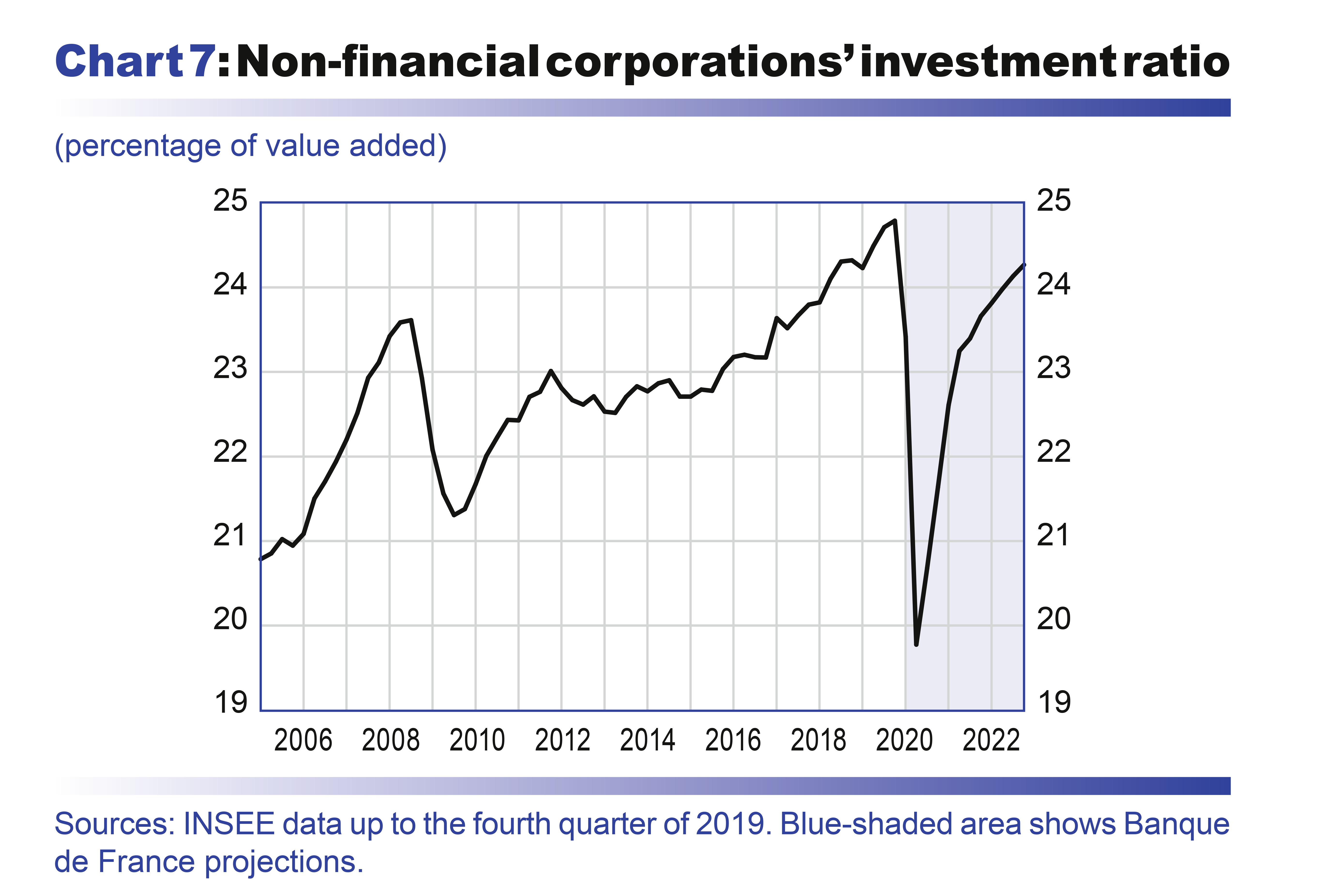

However, the loss of activity is expected to remain considerable at the end of 2022, at around 3 percentage points compared with a pre-crisis projection. This loss should partly reflect a shortfall in demand, but also a reduction in potential activity as a result of the crisis. On the one hand, the fall in investment should limit capital accumulation. On the other, we assume that the shock to the labour market and business failures will affect the economy’s overall productivity (see below). The loss of activity should thus break down approximately equally between potential GDP losses and a widening of the output gap. Beyond this loss in terms of level, potential growth should however be unaffected.

The balance between saving and consumption will be significant in determining the pace of the economic recovery up to end-2022

The lockdown measures at the start of 2020 imposed very tight constraints on household consumption. When combined with the relative resilience of incomes (see below), this means that the household saving ratio should increase sharply. It could thus be close to 20% for the first quarter and peak at around 30% in the second quarter, compared with an average of approximately 15% in 2019.