Working Paper Series no. 686: Measuring “Indirect” Investments in ICT in OECD Countries

ICT components, such as microprocessors, may be embodied in other capital goods not recorded as ICT in National Accounts. Gilbert Cette, Jimmy Lopez, Giorgio Presidente and Vincenzo Spiezia name ‘indirect ICT investment’ the value of embodied ICT components in non-ICT investment. The paper provides estimates of ‘indirect ICT investment’ based on detailed and unpublished Supply-Use tables (SUT) in 12 OECD countries: Australia, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Japan, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

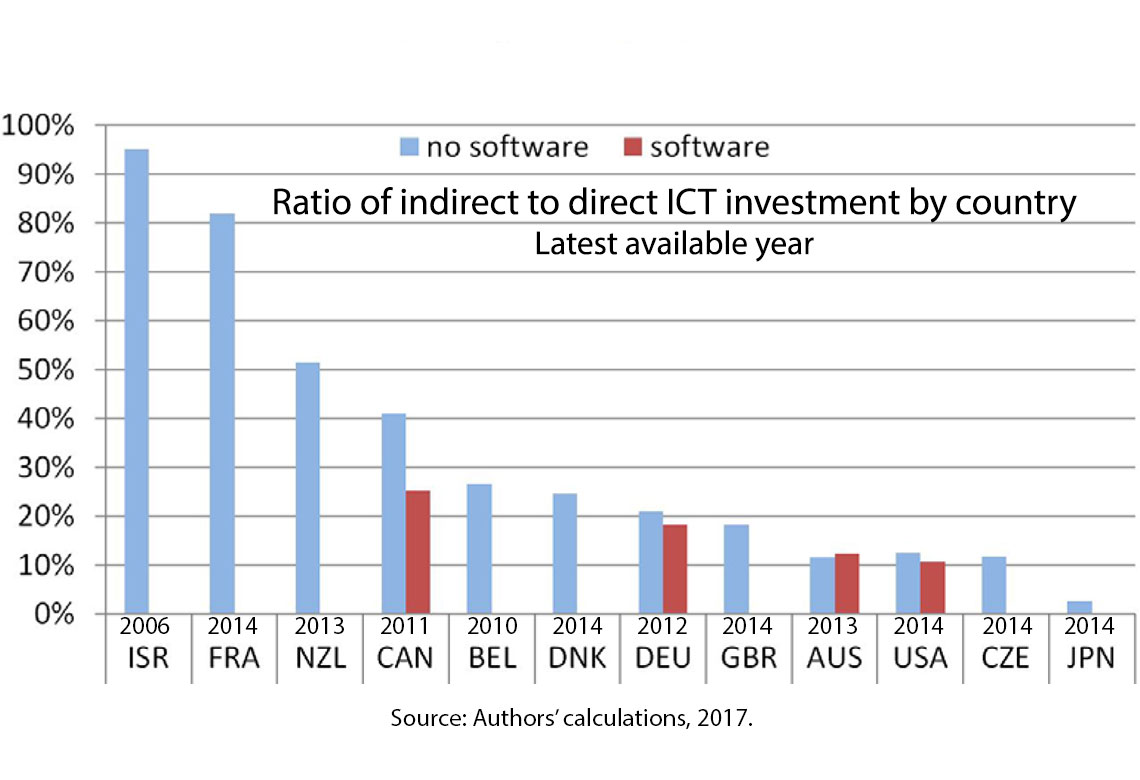

Their main finding is that ICT investment appears significantly higher when considering its indirect component, the average increase being about 35%. The inclusion of indirect ICT investment, excluding software (for which firms’ expenditures are difficult to measure), changes significantly the relative position of countries with respect to the ICT intensity of their investments. The inclusion of software further increases indirect ICT investment but the increase is smaller (in percentage) than without this inclusion. A final result, but concerning only three countries, it that the diagnosis of a stabilisation, or even a decrease, of ICT investment in percentage of GDP or of total investment, observed from the beginning of the century, is not modified if they take into account the indirect ICT investment.

ICT is one of the main drivers of the third industrial revolution. The performance gains of ICT have been huge over the last decades, as shown by the decline of ICT price relative to GDP price in the US national accounts. An abundant literature has been devoted to the evaluation of ICT contribution to growth in the main developed countries. Some main results, among others, are that: i) this contribution is significant, but seems transitory with the main productivity impact during the decade 1995-2005; ii) the US benefit from a higher ICT diffusion than the other developed countries.

ICT diffusion seems to now have stabilized in developed countries, after a multi-decade increase, which is puzzling and does not receive consensual explanation. In 2014, ICT investments accounted for 2.7% of GDP in the OECD, down from 3.5% in 2001. In most countries, the ratio of ICT investment to GDP decreased in nominal terms, i.e. after adjusting for the relative decrease in ICT prices. While the long-lasting effects of the crisis have certainly contributed to this downward trend, in many countries the relative decrease in ICT investment seems to have started well before 2007. Nevertheless, within global investment nominal spending, the ICT share seems stable over the 2000-2015 period, on average among OECD countries, but with differences between countries. It means that ICT investment growth is, on average, more or less identical to global investment growth over that period.

This paper examines a specific channel that may lead to underestimate ICT investments in the System of National Accounts (SNA 2008). According to the SNA 2008, if a firm purchases some ICT equipment, such as a microprocessor or a piece of software, to be used repeatedly in production processes for more than a year, the purchase is recorded as ICT investment. However, if the firm purchases the same piece of equipment or software embodied in other capital goods not recorded as ICT, e.g. a harvester or a metal cutting machine, its value will not be recorded as ICT investment. We label the value of ICT assets embodied in non-ICT investment as “ICT indirect investment”, as opposed to the direct purchase of ICT assets that is already recorded in the SNA as ICT investment. The SNA accounting convention implies that, while the overall investment levels may be correctly measured, the ‘actual’ contribution from ICTs may be masked to the extent that ICT capital is embodied in non-ICT assets. Furthermore, if the ICT embodiment grows over time, the stabilisation, or even the decrease, of ICT investment relative to GDP or total investment, observed from the beginning of the century, could mask an increase in total (direct plus indirect) ICT investment.

The paper investigates the above hypothesis for a selection of OECD countries. We use Supply-Use tables (SUT), which provide information on the supply and use of intermediate inputs by industry, to measure the value of ICT assets embodied in non-ICT investment. The OECD countries considered in the analysis are the twelve ones from which SUTs have been collected at a sufficient level of detail: Australia, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Japan, Israel, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The empirical analysis is carried out for the years when SUTs are available, and can differ among countries. Country differences in data availability explain why the comparison is proposed over 12 countries for indirect ICT investment when we do not include software, but only 4 countries when we include software, and even 3 countries for a robustness check taking into account the share of imports within equipment investment products. Our empirical approach is carried out with data at current prices and not constant ones. From this, we avoid all the numerous problems of quality measurement, which are acute concerning ICT products.

The main result is that ICT investment appears significantly higher when considering its indirect component, the average increase being about 35%. The inclusion of the indirect component - excluding software - raises ICT investment by 95% in Israel, 82% in France, 51% in New Zealand and 41% in Canada. The rise is lower than 30% in the other countries. The inclusion of indirect ICT investment, excluding software, changes significantly the relative position of countries with respect to the ICT intensity of their investments. Israel, which has the fourth lowest share of direct ICT investment in GFCF (4.2%), shows the highest shares of total (direct plus indirect) ICT investment (8.2%), together with the Czech Republic. Similarly, New Zealand and Canada move up in the ranking, from 5.2% to 7.8% and from 4.8% to 6.7%, respectively. In Denmark, indirect ICT investment brings the share of total ICT investment from 5.2% to 6.4%. The inclusion of software, which was possible for only four countries, further increases indirect ICT investment but the increase is smaller than from ICT capital goods: ICT investments are raised by 2.4 percentage points in Canada and by 1.7 percentage points in both the United States and Germany and by 0.9 percentage points in Australia. Finally, from our results, the diagnosis of a stabilisation, or even a decrease, of ICT investment in percentage of GDP or of total investment, observed from the beginning of the century, is not modified if we take into account indirect ICT investment.

The methodology of this paper relies on five hypotheses, namely that i) the ratio of ICT intermediates to output is the same for capital assets and final consumption; ii) for each product, domestic output has the same ICT embodiment as imports; iii) ICT intermediates are not consumed in the production process but “transferred” into the final output; iv) no secondary production takes place; and v) distribution margins and taxes on investment expenditures are negligible. The sensitivity check on hypothesis ii) presented in the paper suggests that its effects may be limited. The remaining hypotheses, however, need to be qualified through the collection of complementary information about the use of ICT intermediates in production within each industry.

Download the PDF version of this document

- Published on 07/30/2018

- 15 pages

- EN

- PDF (903.29 KB)

Updated on: 07/31/2018 12:08