Working Paper Series no. 658: Misallocation Before, During and After the Great Recession

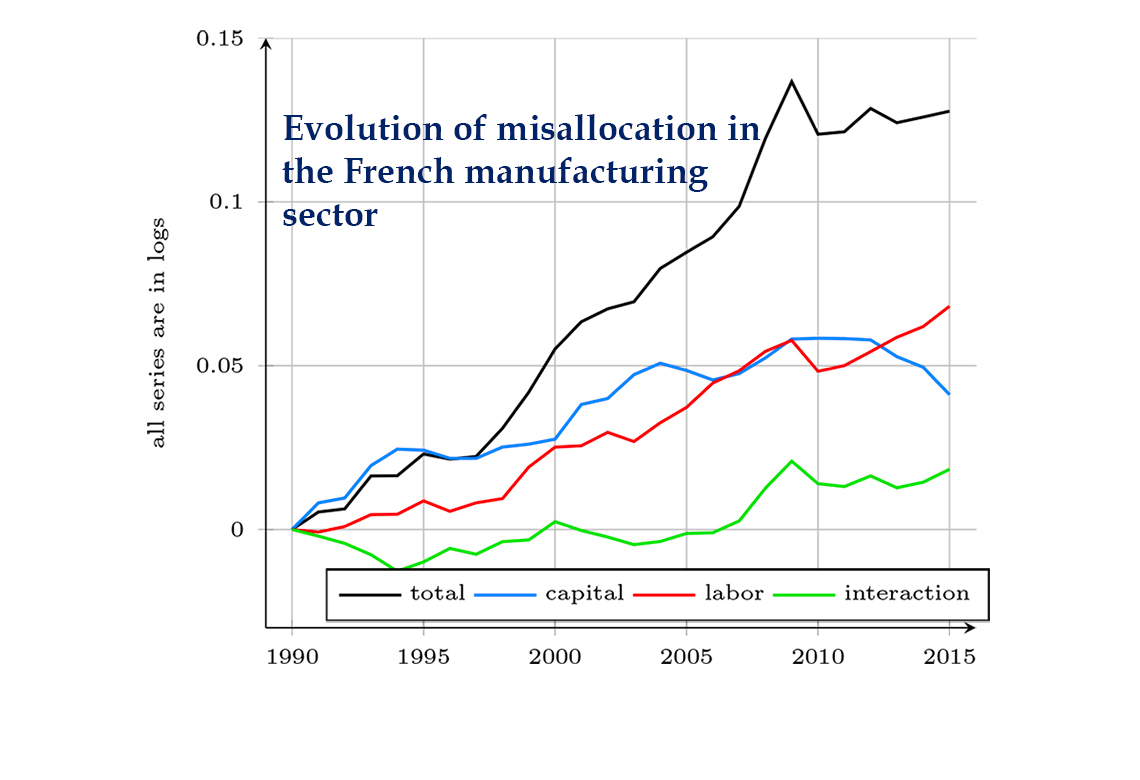

This paper assesses resource misallocation dynamics and its impact on aggregate TFP in the French manufacturing sector between 1990 and 2015. I provide an exact decomposition of allocational inefficiency into three components: labor misallocation, capital misallocation, and a third term representing the interplay between both. Misallocation increased substantially between 1997 and 2007, generating a loss in annual TFP growth of roughly 0.8 percentage points. This increase is mainly related to labor misallocation, except at the beginning of the 2000s, when capital misallocation played the leading role. The impact of allocational efficiency during the Great Recession is sizeable: misallocation accounts for roughly 25% of the 2007-2009 decline in TFP and 20% of the improvement observed in the immediate aftermath of the crisis. The main feature behind the rise in misallocation during the crisis is the predominance of the interplay component, which is stable the rest of the time. It suggests that one should pay special attention to mechanisms disrupting both labor and capital markets in the wake of financial crises. Finally, allocational efficiency remains rather constant after 2010: the post-crisis slowdown in productivity growth is therefore even more pronounced for efficient TFP than for observed TFP.

This paper aims at assessing the loss in aggregate total factor productivity (TFP) that stems from misallocation of factors of production. More generally, this study contributes to the literature relating the dynamics of macro-productivity to determinants at the firm level before, during or after economic crises.

Aggregate TFP obviously depends on micro-productivity, i.e. on the efficiency with which individual firms use their inputs (here labor and capital) in order to produce. However, it also depends on the allocation of these inputs: if one was able to freely reallocate one unit of input from a low-productivity firm to a high-productivity firm, total output would increase while the total stocks of inputs would remain unchanged. Such reallocation would therefore improve aggregate TFP. As a result the dynamics of macro-productivity over time may reflect either changes in micro-productivity or changes in allocational efficiency (also called misallocation). This paper uses recent methodologies to disentangle these two effects. To go further it also decomposes misallocation into three components: the allocational efficiency of labor, the allocational efficiency of capital, and the interplay between both kinds of misallocation.

The framework used to measure misallocation relies on the definition of individual production functions and output aggregators. By maximizing total output one can derive the optimal inputs allocation and the efficient level of aggregate production. Comparing with the observed aggregate output provides a measure of the loss in TFP which can be imputed to misallocation of resources. Assuming that consumers are price-takers and spend optimally the optimal allocation is such that marginal revenue products of inputs are equalized. The ratio between the observed marginal revenue products and their optimal values can therefore be seen as distortions driving the economy away from the efficient allocation. Labor (resp. capital) misallocation is thus measured as the boost in aggregate TFP one would obtain by optimally reallocating labor (resp. capital) in the absence of any capital (resp. labor) distortion. The effect of the interplay between the two kinds of misallocation is then measured as the variation in allocational efficiency that does not come from neither labor nor capital misallocation. This effect asymptotically converges to the covariance between labor and capital distortions and therefore reflects the fact that misallocation worsens when firms which have too much (or too few) labor also tend to have too much (or too few) capital.

This framework is applied to the French manufacturing sector using the FiBEn database. This data set covers the universe of French firms with sales at least equal to 750,000 euros. The time period goes from 1990 to 2015, therefore including the Great Recession and its aftermath. The empirical results are the following: first, allocating inputs optimally would boost aggregate TFP by almost 30% on average. The losses implied by labor and capital misallocation are found to be very similar, close to 14%. The paper shows that firms suffering from a lack of labor input are also firms with relatively high nominal value added, large capital stock and high productivity. Firms that are short of capital input also tend to be highly productive, but have a relatively low nominal value added, low labor input and a dramatically small capital stock. During the decade preceding the Great Recession misallocation generates a loss in annual TFP growth of roughly 0.8 percentage points. This deterioration is mainly related to labor misallocation, except at the beginning of the 2000’s, when the increase in capital misallocation is the main driver. Misallocation reaches a peak during the Great Recession and decreases in the immediate aftermath of the crisis: it accounts for 23 to 31% of the 2007-2009 drop in aggregate TFP, and for 17 to 26% of the 2010 recovery. The striking feature of misallocation during the Great Recession is the effect of the interplay component, which is negligible the rest of the time. Mechanisms affecting both labor and capital markets may therefore be particularly important in the wake of financial crises. Finally, misallocation remains stable after 2010: the post-crisis slowdown in productivity can hardly be explained by allocational efficiency.

Download the PDF version of this document

- Published on 12/29/2017

- EN

- PDF (1.86 MB)

Updated on: 12/29/2017 08:02