Working Paper Series no. 815: No country is an island. International cooperation and climate change.

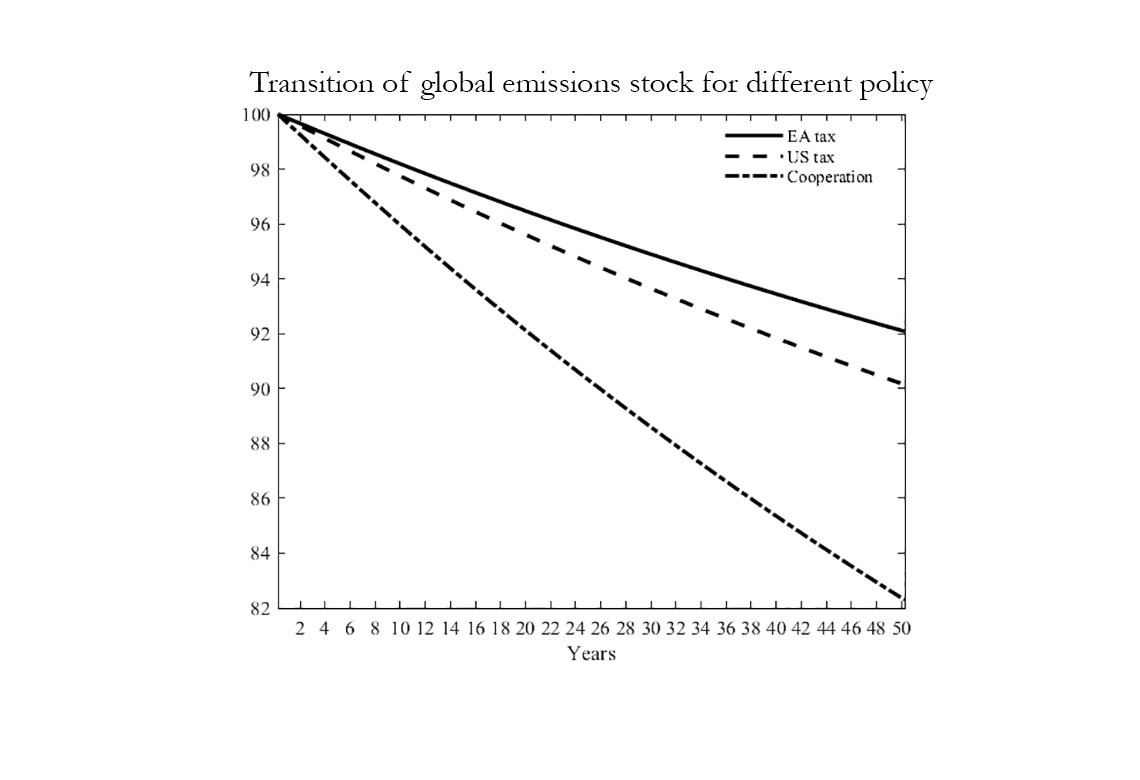

In this paper we explore the cross-country implications of climate-related mitigation policies. Specifically, we set up a two-country, two-sector (brown vs green) DSGE model with negative production externalities stemming from carbon-dioxide emissions. We estimate the model using US and euro area data and we characterize welfare-enhancing equilibria under alternative containment policies. Three main policy implications emerge: i) fiscal policy should focus on reducing emissions by levying taxes on polluting production activities; ii) monetary policy should look through environmental objectives while standing ready to support the economy when the costs of the environmental transition materialize; iii) international cooperation is crucial to obtain a Pareto improvement under the proposed policies. We finally find that the objective of reducing emissions by 50%, which is compatible with the Paris agreement's goal of limiting global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius with respect to pre-industrial levels, would not be attainable in absence of international cooperation even with the support of monetary policy.

The discussion on the impact of climate change and of potential mitigation policies has gained momentum both in academia and policy circles over the last decades. Heatwaves, floods and natural disasters at broad are raising the awareness that the long-neglected costs of adverse climatic events might materialize sooner than expected. Scientific studies, endorsed by international agreements, have estimated that countries should reduce their emissions by about 50% in order to maintain the increase in temperature below 2 degree Celsius over the next century (IMF (2019)). Research networks involving central banks and policy institutions have been created to discuss how to best tackle climate change and how to calibrate mitigation policies. A recent report by the Network for the Greening of the Financial System (NGFS), organized by 87 central banks and supervisory authorities, for example, provides a detailed analysis of the potential impacts of climate change onto the economy and the central banking operations (NGFS (2020)). Despite there exist robust empirical evidences on the macroeconomic costs of higher emission levels (Nordhaus (1994) and Hsiang et al. (2017)), there are relative few structural macro models featuring emission externalities that can be used to analyse the trade-offs of different containment policies. Moreover, most of the existing macro-literature mainly makes use of closed-economy frameworks with no cross-country interaction (e.g., Heutel (2012), Ferrari and Nispi Landi (2020) and Dietrich et al. (2021)). Against this backdrop, our paper provides four new contributions. First, we derive an open economy general equilibrium model where emissions and their spillovers can be studied in a structural framework. In our setting there are two countries, each of which produces “brown” and “green” goods. The two goods are perceived as similar by consumers, but the production of brown goods generates a negative emission externality. In this context, the cross-country dimension is particularly relevant because emissions produced in once country affect also the other. As a consequence, only cooperative actions are successful in reducing climate risk at the global level. In economic terms, this is a coordination problem, as actions produce the maximum benefits only if taken jointly. However, profit-maximizing agents might refrain from doing anything as they would benefit more by waiting for other agents to act. Second, we estimate the model with US and euro area data to study how emissions patterns across the Atlantic have changed over the last 20 years. Notably, in our framework the “social cost” of emissions, which is given by the GDP loss due to emissions in the steady state, amounts to around 1.2% of GDP in the US, a figure which looks more realistic and aligned to the empirical estimates compared to other calibrated models' predictions. Third, we compare different policies that can be deployed to reduce emissions: i) a change in monetary policy objectives, whereby the central bank pursues a double mandate of maximizing welfare and reducing emissions; ii) a change in domestic fiscal policy, whereby fiscal authorities start to directly tax emissions; iii) a change in trade policy, whereby one country implements tariffs targeting polluting imports from the foreign economy. We additionally evaluate the consequences of coordinated and competitive actions by agents. Specifically, we show that the non-cooperative equilibrium is characterized by an insufficient level of taxation on emissions, as both countries attempt to entirely pass the cost of emissions containment on to their respective counterpart. Therefore, only coordinated policies can achieve the climate objective when fiscal and monetary policy interact. Notably, the best policy mix is the one where governments focus on reducing emissions, while the central banks intervene to sterilize the welfare costs of environmental taxation.

Download the PDF version of this document

- Published on 06/08/2021

- 75 pages

- EN

- PDF (4.02 MB)

Updated on: 06/08/2021 09:36