Working Paper Series no. 671: Payments delay: propagation and punishment

Ben Craig, Dilyara Salakhova, Martin Saldias use a unique dataset of transactions from the real-time gross settlement system TARGET2 to analyze the behavior of banks with respect to the settlement of interbank claims. They focus on the time that passes between a payment’s introduction to the system and its settlement, the so-called payment delay. Delays represent the means by which some participants could free ride on the liquidity of others. These delays are important in that they can propagate other delays, thus prompting concerns that they could cause system gridlock. This paper characterizes the delays in the TARGET2 and analyzes whether delays in incoming transactions could cause delays in outgoing transactions. Authors distinguish between the potentially mechanical pass-through of delays and the reaction of one bank to its delaying counterparty, and propose a set of instruments to tackle endogeneity issues. They find evidence that delays do propagate downstream; however, in most cases the effect is rather limited. As for delaying strategies on a payment-by-payment basis, contrary to the theoretical literature, the data show only very weak evidence. This conclusion opens a venue for research how banks may rather follow persistent liquidity management routines.

In this paper, we focus on the negative externality of free-riding on payment systems using payment-by-payment data from Target2 over the period 2008-2014. We analyze banks’ delaying behavior and particularly test two main hypotheses: (i) does a bank react to delays by delaying payments to those counterparties who delay to it, a “strategic reaction” effect? (ii) Does a bank propagate “upstream” delays that are delayed to it, a “pass-through” effect? Our findings suggest that delays do not result from banks’ bilateral punishment game but rather from employed intraday liquidity management practices. At the same time, banks tend to delay more when facing incoming delays.

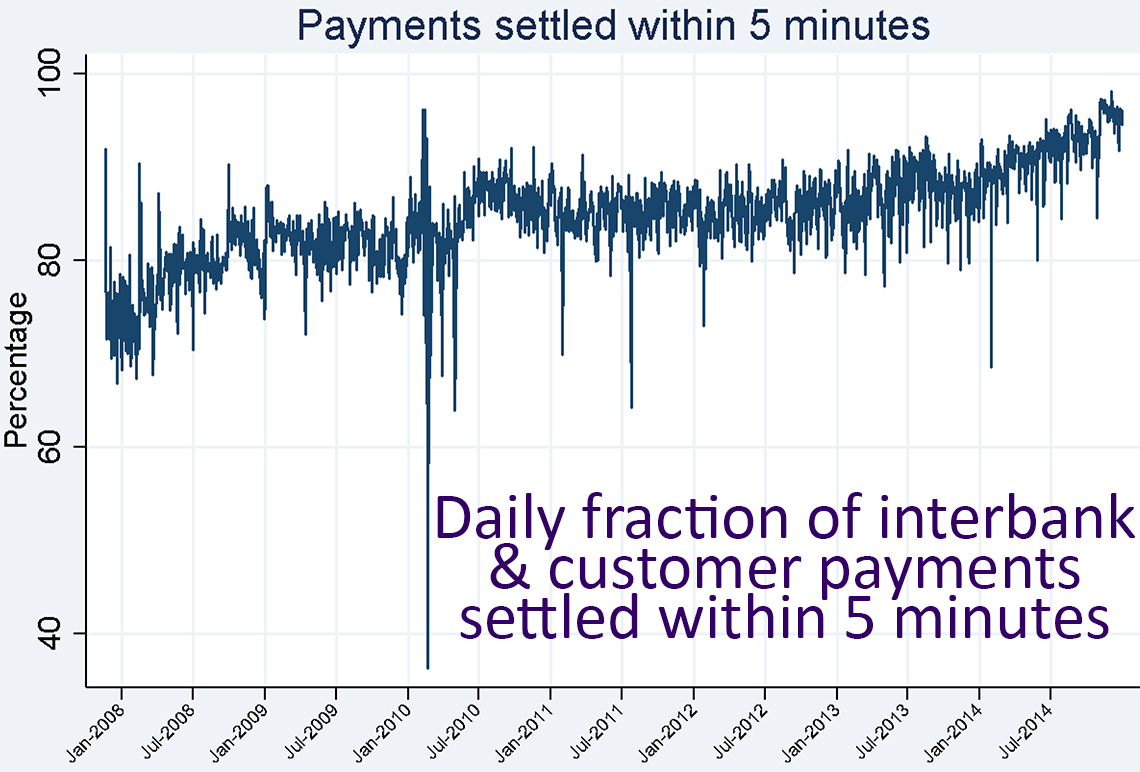

Figure above shows that from 2008 to 2014, on average, only 85% of daily payments were settled within 5 minutes. The simple existence of such delays in a gross settlement system is already puzzling since all payments are to be settled immediately given that banks have enough liquidity to make their payments.

Smooth functioning of financial infrastructure is crucial for the stability of a financial system and transmission of monetary policy. Payment systems play a key role in transmission of liquidity between financial agents. Target2 payment system is the Eurosystem’s Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) system whose yearly turnover reached €470 trillion in 2015, which is equivalent to 30 times Euro area GDP. RTGS systems have advantage over net settlement systems since they settle payments immediately and irrevocably. This allows for reduction in settlement risk but at the same time brings heavier liquidity requirements for participants. As suggested in the literature, when liquidity is pricy, participants may be willing to delay their payments while waiting for incoming payments. Such behavior in certain circumstances can be very disruptive, for example, problems with transferring liquidity between agents may lead to complete freeze of their economic activity. Delays in payment systems have attracted a lot of attention from central banks and specialists in payment systems due to their potential to threaten system's functioning by provoking gridlocks.

We contribute to both theoretical and empirical strands of the payments literature on delays. First, we confirm that banks do delay payments in TARGET2 payments system over the period from 2008 to 2014, and the volume of delayed payments evolves over time. Second, we question the statement made by the theoretical literature that banks delay payments strategically on a payment-by-payment basis as a response to incoming payments being delayed. And in order to do that, we use insights from the literature on econometrics of networks and propose an econometric approach that allows us to distinguish between two types of responses. Namely, a bank reacts by delaying payments only to those counterparties that delay to her, a "strategic reaction" effect, or a bank simply propagates "upstream" delays that are delayed to her, a "pass-through" effect. We treat endogeneity issues by designing a set of relevant instrumental variables.

Our findings suggest a small statistically significant pass-through effect, of the order of a couple of percent of delayed value. However strategic reaction, during the day, is a minor part of delay decisions. In other words, we find that banks do not delay payments strategically to the counterparties that have previously delayed to them on a payment-by-payment basis. If anything, payment delays seem to be rather a part of banks' integral liquidity management practices and probably made at the beginning of the day when banks decide how much liquidity to provide to the system. While decisions made strategically throughout the day have either a minor effect or are absent. It should be noted that all of these results hold for days where there has been no major breakdown in the system.

Download the PDF version of this document

- Published on 03/27/2018

- 27 pages

- FR

- PDF (3.93 MB)

Updated on: 04/25/2018 09:02