Working Paper Series no. 690: The Toll of Tariffs: Protectionism, Education and Fertility in Late 19th Century France

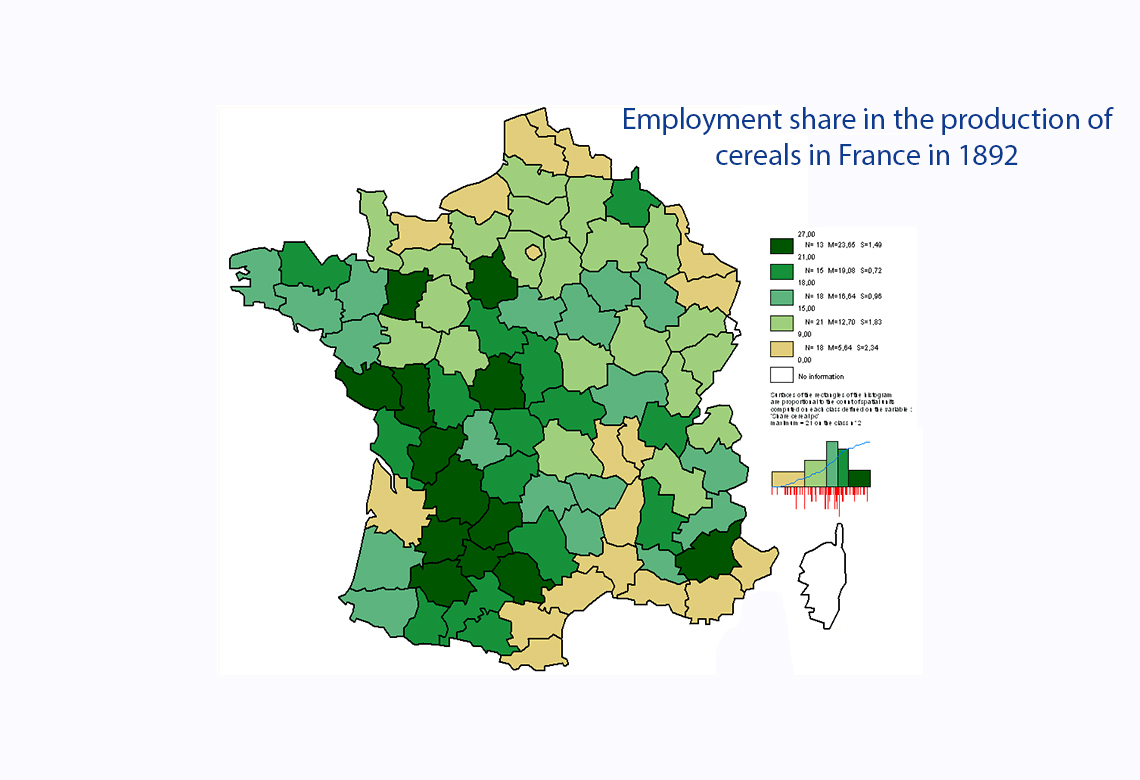

Vincent Bignon and Cecilia García-Peñalosa examine a novel negative impact of trade tariffs and the costs they induce by documenting how protectionism reversed the long-term improvements in education and the fertility transition that were well under way in late 19th-century France. The Méline tariff, a tariff on cereals introduced in 1892, was a major protectionist shock that shifted relative prices in favor of agriculture and away from industry. In a context in which the latter was more intensive in skills than agriculture, the tariff reduced the relative return to education, which in turn affected parents’ decisions about the quantity and quality of children. They use regional differences in the importance of cereal production in the local economy to estimate the impact of the tariff. Their findings indicate that the tariff reduced enrollment in primary education and increased birthrates and fertility. The magnitude of these effects was substantial. In regions with average shares of employment in cereal production, the tariff offset the (downward) trend in birthrates for 13 years; in those with the highest cereal employment shares, there was a delay of up to 22 years.

Conventional economic theory holds that implementing protectionist policies leads to substantial losses. However, these losses are difficult to quantify empirically due to the lack of recent examples of a country that has switched from free trade back to protectionism. To overcome this problem, economists generally simulate the loss in economic growth that would result from a decline in foreign trade following a sharp rise in import tariffs. From this, they then deduce the short-term costs of protectionism. A recent estimate by Arkolakis et al. (2012) suggests that these costs are low. This apparent lack of significant short-term costs nonetheless conflicts with studies of microeconomic data, which show that trade liberalisation has had a significant impact on employment in the United States and France, as well as on the speed of innovation.

The long-term cost of protectionism can be estimated more directly by looking at historical episodes of reversals in trade policy. One prominent example was the reversion to protectionism following the first globalisation boom that took place from the 1830s to the early 1890s. At the time, a surge in grain imports from North America and Argentina had led to a steep drop in cereal prices, and European governments responded by adopting increasingly protectionist agricultural trade policies.

We study the effect of the sharp increase in import tariffs in France in 1892 on levels of education. Protectionist measures known as the Méline tariff were adopted in response to discontent among farmers, whose incomes had dropped sharply following a surge in cereal imports from the Americas (Golob, 1944). This protectionist shock occurred at a time when agriculture did not require much qualified labour. This reduced appetite for new technology in French farming resulted in lower demand for qualified labour and hence education among rural populations. Therefore, by increasing the price of agricultural products relative to manufactured goods, higher cereal tariffs made it more attractive to work in farming than in manufacturing, and hence reduced the relative return on an education.

At the level of the individual administrative districts or départements (hereafter referred to as departments), this negative shock lowered education levels and increased birth rates in proportion to the share of cereal production in local employment. An explanation for this can be found in the unified growth theory developed by Galor and Weil (2000), which holds that demand for education in a particular sector is positively correlated with the degree of technological progress. Rates of school enrolment depend on the benefits economic agents can expect to derive from an education: thus, if the expected return on an education is low, agents have a greater incentive to consume their income, for example by having more children (Becker and Tomes, 1976); conversely, if the return on an education is high, then investment in education should increase and the number of children per family should fall.

To measure the impact of protectionism on the incentive to get an education and modify fertility rates, we estimate regressions for a panel of 85 French departments for the period 1872-1913. We use data from the five-yearly population census to measure birth and fertility rates for women aged 15 to 49. We also use the official statistics on primary education (Statistique de l’enseignement primaire) to construct enrolment rates for children aged 6 to 13 and for those aged over 13, and rates of absenteeism in both summer and winter. To test the robustness of our results, we estimate three different equations.

The impact of protectionism on education and fertility therefore increases according to the degree of exposure to these policies. In our last specification, we show that the findings are similar when we allow for differences in impact over the short and long term. To ensure that our regressions correctly capture the impact of protectionism, we control the results for the level of religious conservatism in the department, the impact of migration and the structure of agricultural landownership.

The results suggest that protectionism has a strongly negative impact over the long term. By reducing rates of school enrolment, the Méline tariff lowered the potential growth of the French economy. If we transpose these findings to today's policy debate, the implication is that protectionism in sectors requiring little qualified labour will lead to a fall in education levels.

Download the PDF version of this document

- Published on 08/22/2018

- 50 pages

- EN

- PDF (745.61 KB)

Updated on: 08/22/2018 10:05