Measuring gains in purchasing power

Measuring “gains in household purchasing power” consists in comparing changes in disposable income in current euro to changes in prices: when disposable income rises more rapidly than prices, there is a “gain in purchasing power”.

In this publication, “purchasing power” is measured using national accounts data. National accounts provide an aggregate measurement of household income in euro, net of taxes and social security contributions, referred to as “household gross disposable income” (GDI). In this case, the term “gross” indicates that no deduction has been made for the physical depreciation of household real estate assets. The major advantage of this measurement is that it covers all income earned by all households resident in France, broken down by source (wages, social security benefits, rental or financial income, etc.) and by type of deduction from income (income tax, social security contributions, etc.). By comparing GDI to the price estimations calculated using the household consumption deflator, we arrive at a measurement referred to as “real” household gross disposable income, or “purchasing power of GDI” (see the summary table at the beginning of these projections).

Nonetheless, this measurement of purchasing power of GDI has two key limitations. The first limitation is that it uses the overall total income earned by all households. While total income may be important for the calculation of GDP growth, it does not provide a complete picture for average per capita purchasing power. However, this can be calculated by dividing purchasing power of GDI by the number of inhabitants to obtain “purchasing power per inhabitant”. According to Insee’s demographic data, the population of France has been rising over recent years by 0.4% annually. Consequently, in order to ensure that there is no decline in “purchasing power per inhabitant”, there must be a “gain in purchasing power of GDI” of at least 0.4% per year. Other, more complex methods for assessing purchasing power also exist. For example, Insee publishes data on purchasing power “by household” and “by consumption unit” (CU). CUs correct the concept of a household in order to take into account the fact that certain expenses such as rent, insurance, internet subscription, electricity bills, etc. are shared among household members.

The second limitation presented by this macroeconomic measurement is far more difficult to avoid within the framework of these projections. It relates to the effects of distribution: aggregating income for households as a whole does not take into consideration specific changes in the income of particular household categories, in the same way that using an average index of price changes does not take into account different consumption baskets within the population. While these factors may be important, it is difficult nonetheless to take them into account in the preparation of macroeconomic projections. The aggregate figures presented in this publication therefore reflect an average change across the population as a whole, which could conceal specific developments within different population sectors depending on their income (see, for example, Insee’s retrospective analyses, France, social portrait and Household income and wealth in the “Insee Références” collection, 2018).

Purchasing power of GDI and purchasing power per inhabitant are expected, on average, to continue the upward trend begun in 2014

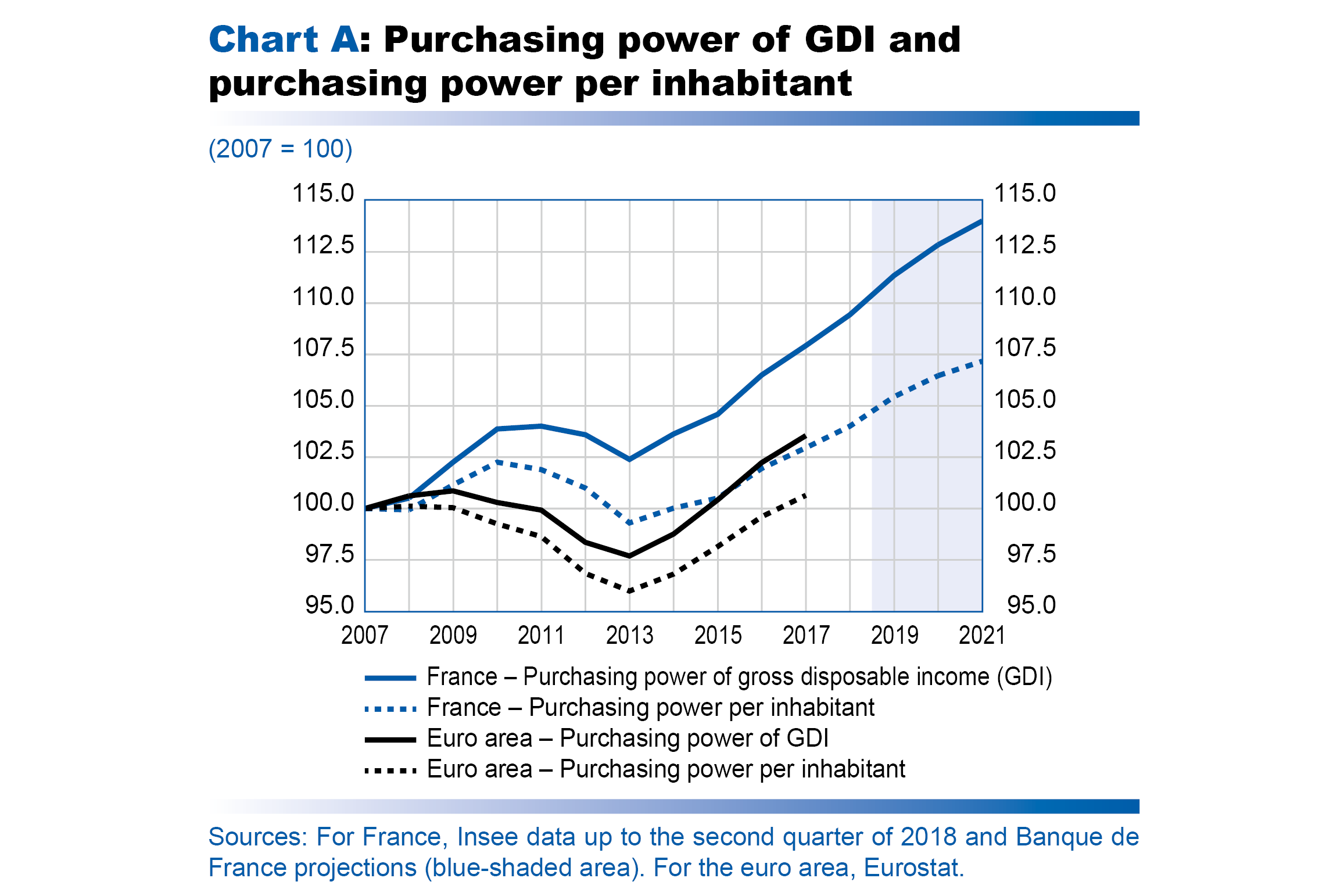

On the basis of the definitions and caveats set out above, we will now analyse recent developments and the projections for gains in purchasing power in greater detail. First, Chart A shows levels of purchasing power, indexed at 100 in 2007, for both concepts – purchasing power of GDI and purchasing power per inhabitant – in France and the euro area.

It demonstrates that purchasing power per inhabitant stagnated between 2007 and 2015 in France: during this period, the slight gains in purchasing power of GDI barely compensated for population growth. After reaching a low in 2013, purchasing power of GDI and purchasing power per inhabitant started to recover in 2014. Purchasing power per inhabitant thus picked up by 1.4% in 2016 and 1.0% in 2017, with an overall improvement of 3.7% between 2014 and 2017.

According to our estimates, which do not take account of the measures to boost purchasing power announced by the government after 28 November (the cut-off date for the preparation of these macroeconomic projections), purchasing power per inhabitant should continue to grow at a similar pace, rising by 1.0% in 2018 and 1.3% in 2019 (corresponding to growth in purchasing power of GDI of 1.4% and 1.7% respectively).

Changes in purchasing power for the rest of the euro area have been more unfavourable than in France since 2007

In the euro area as a whole, changes in both purchasing power of GDI and purchasing power per inhabitant have been more unfavourable than in France since 2007. In particular, the low observed in 2013 was far more pronounced, with a drop of around 4% in purchasing power per inhabitant between 2007 and 2013. Like in France, purchasing power per inhabitant has picked up since 2014, but the euro area had to wait until 2017, rather than 2015 in France, for it to return to its 2007 level. Between 2007 and 2017, purchasing power per inhabitant increased by only 0.6% for the euro area as a whole, compared with growth of 3.0% in France.

Purchasing power has been buoyed by tax measures and labour market improvements

Chart B allows us to deepen our analysis of the situation in France by presenting the four main contributors to annual changes in purchasing power of GDI.

• Labour income, which in the chart is separated out between gross average wages and employment.

• The net effect of social transfers and direct taxes and employees’ social security contributions.

• Other income, which mainly consists of self-employment income, rents and net financial income (interest and dividends paid and received).

• Prices measured using the household consumption deflator (changes in the deflator are deducted from changes in income in current euro to calculate gains in purchasing power). The household consumption deflator incorporates the effect of increases in indirect taxes on tobacco and fuel. These have a significant impact on these projections for 2018-20, as the estimates do not yet take account of the cancellation of the rise in fuel taxes announced by the government after 28 November.

The improvement in purchasing power for the period from 2014 to the end of the projection horizon can be broken down into three distinct phases. In 2014 and 2015, the turnaround in gains in purchasing power was mainly driven by very low inflation, thanks to the sharp drop in oil prices over the period. Nominal income grew slowly, however.

Income growth then gained greater momentum in 2016, and even more so in 2017, thanks to an increase in labour income, particularly with the substantial job creations observed in 2016 and 2017 (see Box 2, “Job creation and unemployment”). Furthermore, as is usually the case when activity picks up, “other income” also gained momentum in 2017, largely driven by the growth in self-employment income. This meant that the gains in purchasing power of GDI were maintained in 2017 despite an upturn in inflation.

In 2018 and 2019, earned income is expected to remain the main driver of gains in purchasing power of GDI, although with a slightly different composition: the pace of job creation is expected to slow but nominal wages are projected to gradually improve, in line with increased productivity (see Box 2). In particular, the average per capita wage in the private sector is expected to increase in 2019 by 2.3% in nominal terms, after 1.6% in 2017 and 1.9% in 2018. Moreover, the net effect of social security benefits received and direct taxes and social security contributions paid should underpin nominal income growth, particularly in 2019 when October 2018’s cut in employees’ social security contributions will bear upon the entire year. The measures announced since 28 November should lend additional support.