Banque de France Bulletin no. 226: Article 3 The European Union’s 2021-2027 multiannual financial framework: new balances, new challenges

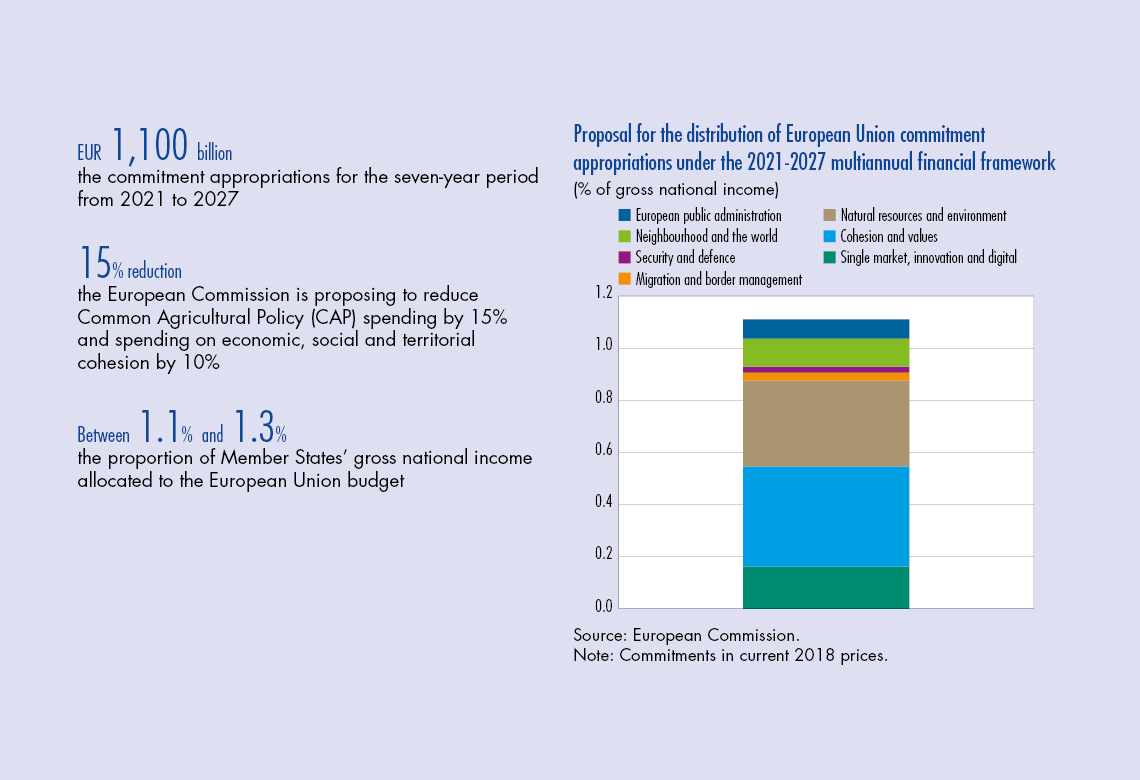

The ongoing negotiations on the next multiannual financial framework for the European Union (EU) were launched 18 months ago by the European Commission. This framework, discussed between the Member States, sets out the EU’s main areas of spending and their ceilings over a seven-year horizon. Due to Brexit and the European parliamentary elections, the outcome of these negotiations was pushed back to autumn 2019 and should be concluded in early 2020. The multiannual financial framework negotiations reflect the power dynamics at play within the EU and highlight the major issues that currently jam the machinery of European integration. The debate on the euro area budget has been relaunched but shows the extent to which fiscal union, the missing piece of the Economic and Monetary Union, exacerbates differences in national positions.

1 The European Union budget: an atypical instrument

An instrument historically controlled by the Member States

From the outset, EU fiscal autonomy has been a major sticking point in the debate on European integration. In 1951, the European Coal and Steel Community budget was independently run and entirely funded by levies on coal and steel production. However, the budget of the EU, and before that, the European Economic Community, is fixed with the agreement of Member States and financed through their contributions, calculated as a percentage of their nominal GDP. This system was initially intended to be transitional until contributions were eventually replaced by the EU’s own resources, independent of Member States and definitively allocated to the Community, without the need for further negotiations with national authorities.

Own resources (mainly customs duties on imports from outside the EU) were only introduced after heated negotiations in 1970. In 1988, as own resources were no longer sufficient, national contributions in the shape of a resource linked to the gross national product of each Member State were reintroduced to finance the EU budget. These have since been gradually increased and are now the primary resource.

Two key moments in the history of the EU budget are worth highlighting.

- From 1975 onwards, responsibility for adopting the annual budget, which had initially been the preserve of the European Council, was shared with the European Parliament. However, between 1979 and 1984, the widening gap between requirements and available resources created a conflictual climate in interinstitutional relations and the proposed budgets were repeatedly rejected by Parliament. The concept of “multiannual financial perspectives” was thus developed to plan spending in the medium term and to lock in interinstitutional agreement in advance. Finally in 2009, the Treaty of Lisbon transformed the multiannual financial framework (MFF) into a legally binding act.

- After years of disagreement and obstruction to European integration, it was decided in 1984 that the United Kingdom’s contributions should be partly reimbursed as the British gained little from the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which accounted for the majority of the EU budget. This is the famous UK rebate or “British cheque”.

A public budget but without all the characteristics

The adoption of a budget is a very different political process for the EU from that of its Member States. Preparing the MFF involves setting out, in broad terms, the spending limits for the Union, the priority areas for…

Download the PDF version of this document

- Published on 12/13/2019

- 10 pages

- EN

- PDF (306.76 KB)

Bulletin Banque de France 226

Updated on: 12/13/2019 14:40