Growth factors in developed countries: A 1960-2019 growth accounting decomposition

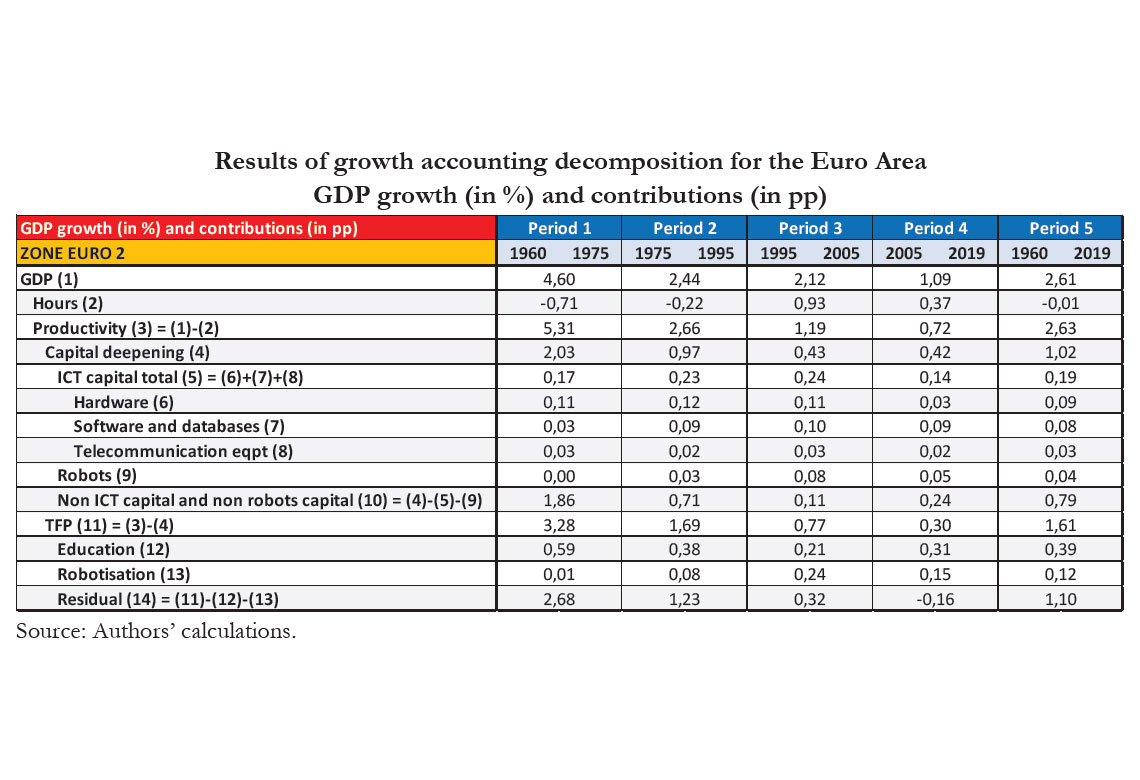

Using a new and original database, our paper contributes to the growth accounting literature with three original aspects: first, it covers a long period from the early 60’s to 2019, just before the COVID-19 crisis; second, it analyses at the country level a large set of economies (30); finally, it singles out the growth contribution of ICTs but also of robots. The original database used in our analysis covers 30 developed countries and the Euro Area over a long period allowing to develop a growth accounting approach from 1960 to 2019. This database is built at the country level. Our growth accounting approach shows that the main drivers of labor productivity growth over the whole 1960-2019 period appear to be TFP, non-ICT and non-robot capital deepening, and education. The overall contribution of ICT capital is found to be small, although we do not estimate its effect on TFP. The contribution of robots to productivity growth through the two channels (capital deepening and TFP) appears to be significant in Germany and Japan in the sub-period 1975-1995, in France and Italy in 1995-2005, and in several Eastern European countries in 2005-2019. Our findings confirm also the slowdown in TFP in most countries from at least 1995 onwards. This slowdown is mainly explained by a decrease of the contributions of the components ‘others’ in the capital deepening and the TFP productivity channels.

One paradox has appeared over the last decades: in the developed countries, and whatever their individual development level, we observe at the same time a continuous productivity slowdown and an increase of the diffusion of ICTs and robots, and even the emergence of the use of digital technologies. This paradox has not yet received any consensual explanation. The aim of this study is to raise some characteristics of such a paradox. By developing a new database, it contributes to the growth accounting literature with three original aspects: first, it covers a long period from the early 60’s to 2019, just before the COVID-19 crisis; second, it analyses at the country level a large set of economies (30); finally, it singles out the growth contribution of ICTs but also of robots, which, following the SNA definition, is bundled in non-ICT capital.

The original database used in our analysis covers 30 developed countries (*) and the Euro Area over a long period allowing us to develop a growth accounting approach from 1960 to 2019. This database is built at the country level and contains several variables such as GDP, hours worked (employment and average working time), ICT and non-ICT capital, number of robots and education level. As much as possible, each of these variables is built in a harmonized methodology for all countries. Several sources were used to build this database, assuming explicitly some usual assumptions.

Our growth accounting approach shows that the main drivers of labor productivity growth over the whole 1960-2019 period appear to be TFP, non-ICT non-robot capital deepening and education. The overall contribution of ICT capital is found to be small, although we do not estimate its effect on TFP. The contribution of robots to productivity growth through the two channels (capital deepening and TFP) appears to be significant in Germany and Japan in the sub-period 1975-1995, in France and Italy in 1995-2005, and in several Eastern European countries in 2005-2019. Our findings confirm also the slowdown in TFP in most countries from at least 1995 onwards. This slowdown is mainly explained by a decrease of the contributions of the components ‘others’ in the capital deepening and the TFP productivity channels.

We are still waiting for a large productivity benefit from the third industrial revolution: the digital one. We know from previous industrial revolutions that it may take decades to get a large productivity benefit at the global level from promising inventions and innovations. If we extrapolate that, it could take a long time for the full impact of the digital revolution to be felt in productivity statistics at the global level. If this explanation is the right one, we could benefit in some years or decades from a dramatic productivity revival. Otherwise, developed countries would face with difficulties the numerous challenges of the future

(*These countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Latvia, Mexico, The Netherlands, Norway, New Zealand, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States)

Télécharger la version PDF du document

- Publié le 07/10/2020

- 24 page(s)

- EN

- PDF (2.51 Mo)

Mis à jour le : 07/10/2020 15:53